“Hillary Clinton was angry and defensive the entire time—no smile and uncomfortable—upset that she was caught wrongly sending our secrets,” Republican National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus said on Twitter.

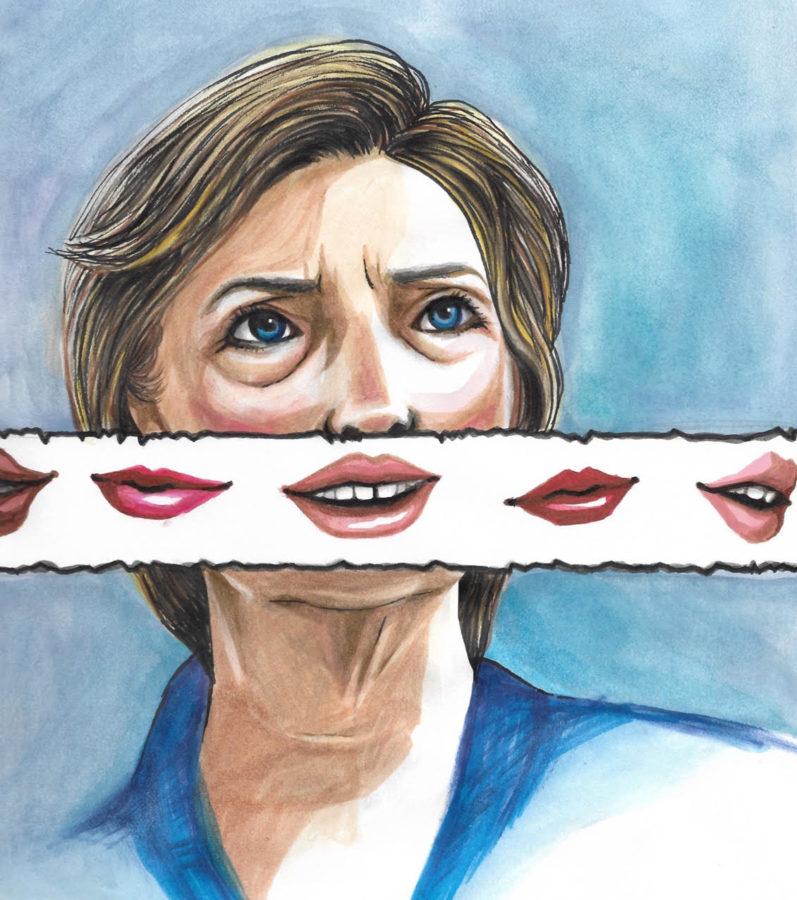

Though currently the most obvious example due to the spotlight of the presidential election, Hillary Clinton has been only one of many women told to smile. After Serena Williams won a physically exhausting quarterfinal match at the 2015 U.S. Open, she was told to smile by a male journalist. At the third Republican debate, when Carly Fiorina acted no differently than the 10 other men on stage, she was the only one told to smile more. Most familiarly, random strangers tell women in their day-to-day lives to smile. This subtle form of harassment exemplifies a common misperception about women: smiling marks one’s femininity, and as Marianne LaFrance, a professor of gender and sexuality studies at Yale, put it: “it falls to women to do more of smiling because we want to make sure women are doing what we expect them to do, which is to care for others.” Women are told to smile, and not men.

In a study conducted by Lisa Barrett, a psychology professor at Northeastern, male and female faces were photographed in various poses from smiles to frowns. These were then shown to test subjects, who were asked why these faces appeared the way they did. Were they being emotional or rightfully upset from a cause? From looking at these faces, the subjects attributed an internal, emotional cause to women yet a situational cause for men. As the election so helpfully underscores, a woman who is not smiling is falsely assumed to be angry or upset, while a man with that same facial reaction must be focusing on serious matters.

Why does it matter that women are told to smile more? This discrepancy is not merely rude or unpleasant: it’s actually harmful, and perhaps underlies why so many gender-based discrepancies still exist in the workplace. It’s one story to see a glass ceiling in which women cannot advance while men can in male-dominated fields like finance, but it’s another to see a glass escalator for men to advance in female-dominated fields like nursing while women are discriminated against. Men earn more than women in female-dominated jobs. White men in particular can easily move up into supervisory positions. Needless to say, men are hardly better performers in these jobs than women are; it’s simply that they fit the prototypical stereotype of a manager. Telling women to smile perpetuates the idea that if they don’t, they’re unlikable and untrustworthy. Telling women to smile perpetuates ideas of male dominance because a woman in a public space is not there for herself but there to respond to a man’s request to smile. This disparity results in far-reaching consequences that affect not only the day-to-day lives of women, but their overall chance of long-term success. To see it reach the national level of the presidential election in which Hillary Clinton is reprimanded for being a “bitch” while Trump is simply seen as serious about the debate is the most disheartening.

Progress has surely been made for women; the number of women in the workforce has more than doubled from 31 million to 67 million since 1970. Still, when women who hold the same qualifications and experience apply for the same jobs as men and end up with a lower starting salary, there is still evidence of a deeply rooted problem. A female presidential candidate from a major party, while an important symbol, is not enough. Neither is the presence of programs to help women enter typically male-dominated fields. It’s not that the gender gap has closed because of this progress—these opportunities are useless without uncovering the root of the cause in the first place. It’s that the gender gap can close because of it, but it has to start with changing society’s perception of women.

Jasmine Wu is a second-year in the College majoring in philosophy and economics.