Party affiliation as a form of identity is so obvious we often don’t have to think about it. What’s strange is that voting is often a secondary condition to this initial label. It doesn’t strike anyone as noteworthy that we say, “I’m a Democrat,” instead of, “I usually vote for Democrats.” Most of us identified with one party or the other by middle school, long before we could actually cast votes. Your actual voting record usually comes after the label, not before.

Maybe that isn’t an entirely bad thing. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see the extraordinary spectrum of ideologies encompassed on either side of the aisle. A devout member of the Tea Party is nothing like John Kasich. A socialist is not interchangeable with a business-friendly, socially liberal centrist. Evidently, labels aren’t particularly informative insofar as political priorities are concerned.

But party labels do influence our behavior in at least one dangerous way. Somewhere along the road, “I’m a Democrat” becomes a point of deeply ingrained pride for many partisans. And the price of proudly identifying with major parties has been made clear in this election cycle. You have to stick with them. If you want to retain the label, you have to “prove” your loyalty to the party. This demand for loyalty is why Republicans who abhor Trump were nevertheless coerced into supporting him, both in the upper echelons of party leadership and amongst ordinary voters. A buffoon who initially inspired more laughter than support managed to twist enough Republican arms to eventually establish a supposedly serious candidacy. He did so in part by playing on this misguided notion of voter loyalty, with help from the Republican National Convention apparatus. And it took a vulgar recording of him bragging about sexual assault to reverse the flow of involuntary endorsements, after months of racist and sexist blunders that had no impact at all.

Trump’s candidacy perhaps most vividly demonstrates that a voter has no obligation to prove himself to a party; it’s the party’s onus to prove itself to the voter. Any decent democratic system respects the individual voter’s autonomy, yet it has become commonplace for voters to be shamed and ostracized into supporting candidates they don’t like on the basis of one tenuous common affiliation.

In normal election cycles, this expectation might be innocuous. Democrats will cast ballots for a Barack Obama and Republicans for a Mitt Romney. Since both choices are relatively qualified, the fact that the minds of most Americans are made up before the race begins is unfortunate, but not necessarily calamitous.

But being a Democrat in the past is absolutely not a requirement to vote only for Democrats today. Republicans who don’t like sexual assault shouldn’t be told that their party membership is contingent on supporting Trump; a Republican voter owes nothing to anyone or anything, least of all to a nominee, by virtue of having voted Republican before. The nominee is the only person whose party affiliation obliges them to anything; if you run on a party’s platform, your policy proposals should line up with the general sense of your party’s values.

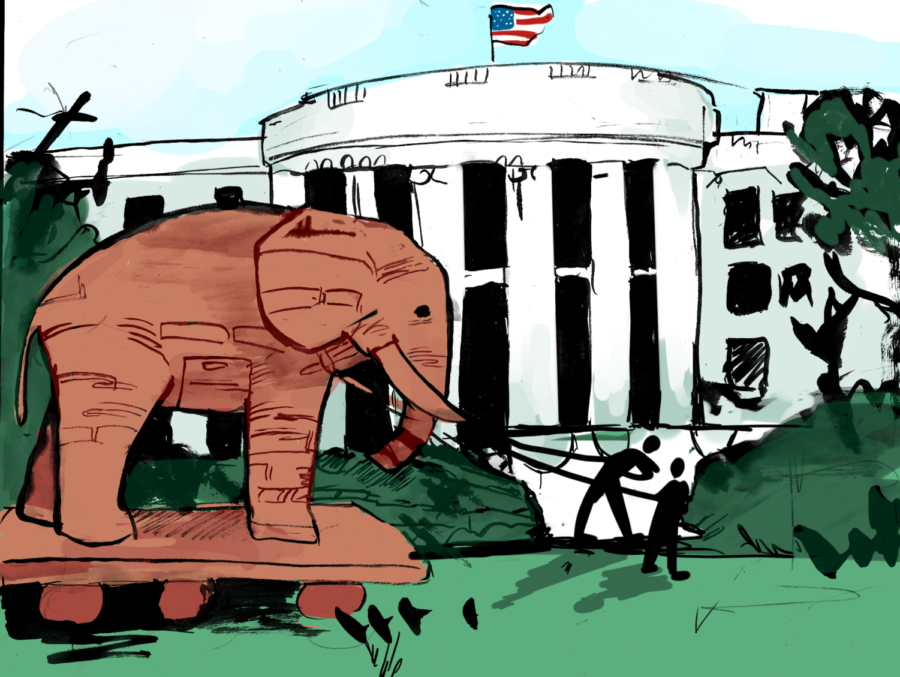

If a Republican feels like the nominee does not accurately represent their party’s true ideology, there should be a way out. A rational understanding of what the label “Republican” means (that is to say, an attachment to a philosophy, not a blank check to whomever claims the party’s mantle) ought to oblige an uneasy voter to run like hell. Yet what happens is just the opposite. You’re a traitor to the party for doing precisely what you should be doing. You’re no longer a real Republican, according to the rest of your party. The result is that people who are uncomfortable with Trump, and all that he stands for, risk being accused of treachery themselves. In this perverse understanding of party politics, being a Republican is utterly divorced from your conservative proclivities. Voters are considered Republican only if they support Trump, a candidate who doesn’t even have enough coherent policy proposals to be considered a true conservative himself.

If the Republican Party expected unconditional support, it should have worked to earn it. Yet its eight years out of power were all spent pushing an obstructionist agenda in Congress. This agenda was never articulated beyond “stop Obama”—hardly the basis for inflexible demands on voter loyalty. And this year, the Republican Party seems to have abandoned its base altogether, pandering to the last splinters of the KKK rather than to the bulk of the party’s followers. If the Republican Party is not willing to disavow the demagogue who has hijacked the steering wheel, it has no right to demand party loyalty from anyone. The notion that blindly sticking to a party nominee is a point of pride shows just how far the political arena has degenerated.

Ultimately, the problem with such stringent party labels is not that they necessarily give us a misplaced sense of identity. The real issue is that voting becomes a matter of proving yourself as a Republican or Democrat, and not as an American. Loyalty to a party seems like a more frequently cited election issue than loyalty to the country—for which these parties ostensibly exist. The second a voter agrees that good Republicans always support the party nominee, that voter makes party survival a priority at the expense of national welfare. Perhaps even scarier than the Republican nominee is that most voters implicitly accept this party-loyalty statement without hesitation. The fact that Trump is a Republican does not mean that this lesson has no relevance to Democrats; the terrible candidate of tomorrow could easily be representing the Democratic Party.

While the party itself has separate and legitimate interests, party affiliation is not intended to feed into some monstrous, self-serving organism. A Republican is supposed to be a conservative-leaning voter whose vote goes to the candidate he thinks is best for America. But the Republican Party of today does not treat its voters like rational beings with a monumental decision to make. It would rather treat them as little more than automatons, whose hesitancy is proof not of the party’s failings but of the voters’ deficiencies. Republican voters’ support is assumed and never earned. They ought to be insulted.

Natalie Denby is a second-year in the College majoring in public policy.