On a Saturday night in October of 2009, Lady Gaga stood in front of one of her largest audiences to the date—12 million Americans, all tuned-in to Saturday Night Live. When the lights went up for her second set she stood completely still on a small platform. Silver rings wrapped around her torso, and giant sunglasses obstructed her eyes and face. As the music began to play, the platform started to spin and the rings twisted around her body like a gyroscope, drawing attention away from everything but the flashiness of it all.

Two years later, returning to SNL for the 36th season finale, she was just as theatric—crawling from an egg to sing her anthemic Born This Way. Another two years after that she took to the SNL stage again, lying on it bare as singer R. Kelly did push-ups over her body. By that point, in the middle of the swing-and-miss of her third album Artpop, Lady Gaga audiences knew to expect the unexpected. Her theatrics were so commonly anticipated that they lost most of their appeal and any thematic thread.

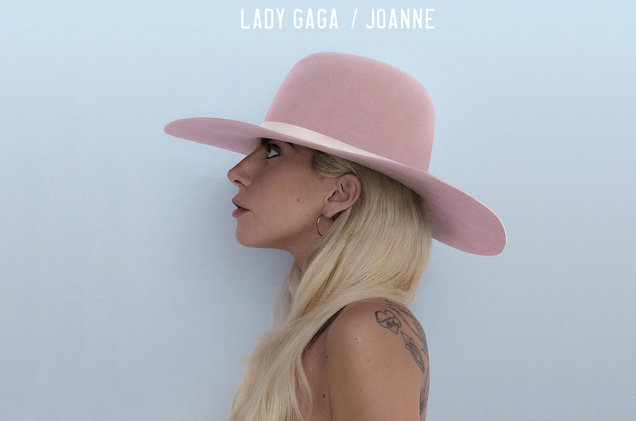

When Lady Gaga performed on SNL for the fourth time in October of 2016, her audience—15 million this time—saw something new. No gaudy set-pieces, no elaborate costumes. The only glaring piece of theatrical flair was a bright pink cowboy hat—the symbol of her new album, Joanne, and her new MO: a more personal subtlety, at least compared to her previous work.

Joanne is Lady Gaga’s fourth studio album, and it positions itself as a deviation from the star’s norm. Born Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta, Lady Gaga’s second name is in honor of a late aunt who died before the star was born. Thus Joanne is both a self-titled album and a memorial. To match the personal weight, Gaga moves away from pop to a blend of genres that comes together for a nice thematic cohesion.

The first two singles, “Perfect Illusion” and “Million Reasons,” sit at opposite ends of the spectrum. “Perfect Illusion” begins with the steady and unfaltering whine of electric guitar and devolves into a screaming, key-changing rock complaint about fake love. Thinned down and acoustic, “Million Reasons” is a country-esque cry from a struggling heart. Despite their differences in style, the songs fit together perfectly in message. Both songs, and the rest on the album, disavow autotune and most vocal processing—a trait that heightens the album’s emotional viscerality, and a stark contrast to the overly-produced Artpop.

Gaga’s authenticity is never more raw, however, than on the album’s title track. “Joanne” has what initially sounds like very imperfect vocals—shaky and emotional throughout each verse—but these are put in opposition to a soft, powerful chorus that only grows in intensity. Though Gaga never had the opportunity to meet her aunt, she translates so easily her family’s pain and a more universal confusion over loved ones lost.

Most of her tracks about women, both generally and about specific, meaningful women in her life, have this natural ease. Her collaboration with Florence Welch of Florence + the Machine on “Hey Girl” has a groovy melt that echoes the sympathetic female empowerment it praises. “Grigio Girls”, abonus track, tells of Gaga’s friend Sonja and how their group of friends dealt with Sonja’s recent cancer diagnosis. The care in her voice on these songs is almost startling, and she has, strangely, never felt more human than she does letting out the line, “Spice girl in this bitch!”

However small bits of the old, showy Gaga show up from time to time. Her fascination with country music turns to lust on the song “John Wayne”, in which she yearns for a physical embodiment of the country concept: “Every John is just the same/I’m sick of their city games/I need a real wild man/I’m strung out on John Wayne.” It’s odd, if you know that John Wayne hardly represents this wildness and reality that these lyrics suggest she seeks. Just like Stefani Germanotta adopted the stage name Lady Gaga, Marion Morrison adopted the moniker John Wayne—a more palatable, commercialized name for his career and the eventual fame in highly fictionalized Westerns. The song, a rock-pop smash, is the most like Gaga’s older work—latching onto some name or concept and pushing its limits à la her Judas or Donatella—and the one that’s the most like an act.

During her first live performance of songs from the album (for her Bud Light Dive Bar Tour) some of the only words unsung were whispered with a forced, deep drawl into the microphone, “My name is Lady Gaga … But if you could do me this favor and tonight if you could just call me Joanne.” Putting on a thick, fake accent is a bit of a disservice to the album’s attempt at authenticity, and is silly enough to make you cringe. Similarly, adopting her late aunt’s name for the stage is kind of weird, even if just for the sake of one performance.

But this is Lady Gaga: The same artist who wore a meat dress to the MTV Video Music Awards. She’s wild—a mega-performer—and this album and the persona she’s adopted, in their small experiments with style, never forget that. Instead they build upon it, making her an artist who grows, and who’s conscious of what she can be.