A Pulitzer Prize–winning Malaysian-Chinese-American journalist delivered a lecture on China’s recently repealed one-child policy on campus Tuesday.

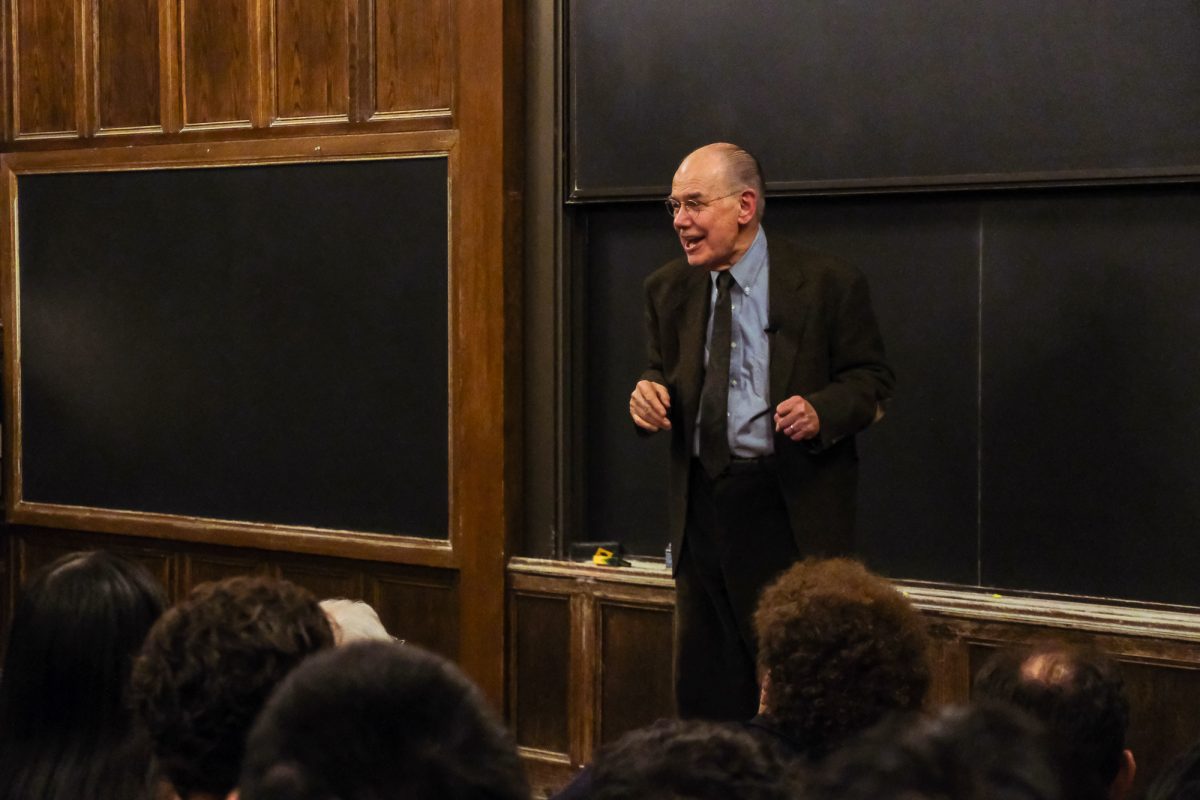

Mei Fong, a former Wall Street Journal staff reporter, spoke at the 57th Street Bookstore about her latest book, One Child: The Story of China’s Most Radical Experiment. The discussion was moderated by Jonathan Eig, a correspondent for the The Wall Street Journal.

Fong began with an explanation of the radical one-child policy and how the stereotypes and thought patterns caused by the policy influenced her childhood in Malaysia. Giving nod to her book title, she said that the policy, implemented in 1980, was the world’s most radical social experiment, with so little planning but such a broad impact. Though it was recently repealed in 2015, the impacts are still prominent all over China.

She likened the policy to a real-life version of something out of George Orwell’s 1984. Fong spent extensive time covering China as a Wall Street Journal reporter prior to and during the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, where she learned firsthand about the enormous impacts of the policy. In her encounters with local factory workers and rural families, Fong learned just how disturbing the effects of the policy were. Police enforced the law by demanding harsh fines (ranging from 2 to 10 times annual income), confiscating property, and terminating employment.

“Even within China, ideas of what happened are walled off from much of the population. I just try to tell who these people are, and how the population police [did] their jobs,” Fong said. Countless women were forced to have abortions, and the fines collected from lawbreakers became a source of revenue.

Fong discussed what she considers one of the biggest issues that resulted from the policy: The imbalanced family now has four grandparents and two parents that will all require the financial support of a single child. Citing a statistic from another book, Fong said that a little known fact is that China’s population of seniors alone would be the world’s third largest population. “The little emperor becomes the little slave,” Fong said, regarding the single child. This one child, who is often spoiled growing up, suddenly must support six people.

After her talk, Fong took questions concerning the policy and her book. She spoke briefly with an audience member about the issues surrounding Chinese women that come to the U.S. seeking asylum because of forced abortions they suffered under the one-child policy. Fong also brought to light some of the studies conducted that compare the children born before and after 1980, and their differing character traits. “Although most studies were inconclusive, according to one study, the children born after the implementation of the policy in 1980 were less generous, more risk averse, and more pessimistic,” Fong said.

One Child: The Story of China’s Most Radical Experiment is currently available for purchase at 57th Street Books and Seminary Co-Op.