“W”s are flying; Old Style is pouring. With the curse finally lifted, Chicago is jubilant. It took 108 years and an extra inning, but the Cubs narrowly edged out the Cleveland Indians for this year’s World Series title. But as Chicago continues to celebrate, decked in royal blue, we cannot forget that the losing team came tantalizingly close to winning and having their own Indians-themed parades—and that’s a problem.

Chief Wahoo, the official mascot of the Cleveland Indians, is racist. There are no ifs, ands, or buts about it. Wahoo reduces an entire nation of people into a red-skinned caricature with a rascally grin. Various Native American activists and scholars, including novelist Sherman Alexie, have decried Wahoo’s feather, which mocks the ceremonial value of eagle feathers. Moreover, Wahoo has been rightfully likened to the racist Little Sambo trope. While the debate on Native American names and iconography is unfortunately far from new, Chief Wahoo is so blatantly offensive that the Cleveland Indians cannot even adopt other Native American–themed teams’ excuses. Other teams using Native American–inspired names are far from innocent, but many at least make efforts to aid Native American causes. The Chicago Blackhawks, for example, donate to Native American organizations and foundations, while Florida State University maintains a close relationship with the Seminole Tribe of Florida and claims a reverent representation of Chief Osceola in their pregame pageantry. This hardly excuses the mostly white crowds tapping their mouths in cartoonish war cries and wearing headdresses like teenagers at Coachella. But Cleveland’s only excuse is that Chief Wahoo is part of their long-standing history and thus cannot be changed. This heritage-based appeal is suspiciously similar to common defenses of the Confederate flag.

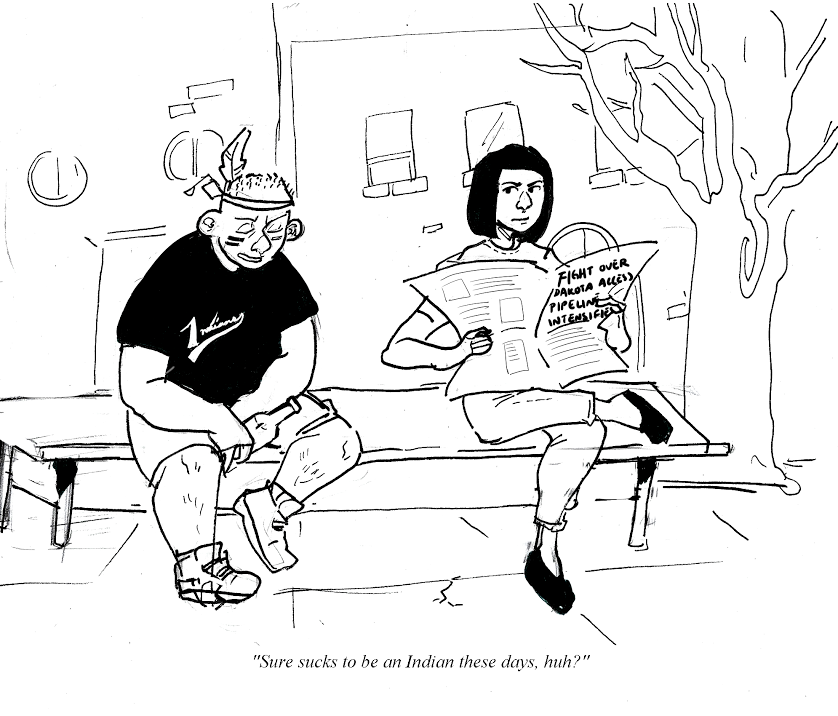

Native American mascots disrespect the people they mock by relegating them to the past, perpetuating grotesquely outdated stereotypes while turning a blind eye to contemporary problems. Before Native American culture was appropriated, the American government unashamedly appropriated Native American land. Modern-day reservations are in many cases impoverished. In fact, the nation’s lowest per capita income rate is found in the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. The economic conditions have turned reservations into veritable food deserts, resulting in Native Americans suffering from a disproportionate obesity epidemic. Other land issues continue to affect Native American communities, whose recent confrontations with police at the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota belie any myth of progress in government–Native American relations.

On the same day, Cleveland fans—many of whom, judging from camera cuts, were beer-bellied white dads with face paint and feathered headdresses—restrained tears during a dramatic Game Seven, Native Americans in North Dakota were restrained and pelted with tear gas. The construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline poses yet another example of encroachment into Native lands—with dire ecological consequences—and the sustained, brutal police reaction to protests is a grim reminder that Native Americans, proportionally, suffer the highest rate of law enforcement homicides.

In light of these pressing issues, I hope the Cleveland Indians will actually address their problematic logo situation, as Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred promised in the aftermath of the World Series. The Indians’ previous compromise—reverting to the block C logo while retaining Chief Wahoo on jerseys—was hardly substantive, though it was more of a step than those taken by the offensively named Washington Redskins when they came under fire. Perhaps it is unsurprising that many white Americans are oblivious to Wahoo’s racism, considering that a demagogue, whose campaign is predicated on blatant racism, is a candidate for the Oval Office. It is no coincidence that Trump leads the polls in the Indians’ home state, a crucial swing state.

Election results and mascot changes won’t solve this country’s deeply ingrained race problems overnight. But Chief Wahoo—a stereotype even older than the Cubs’ previous win, and one that does not belong in the 21st century—has simply got to go. The Cubs proved that it’s possible to break a decades-long curse. Racism is a tougher curse to banish.

Felipe Bomeny is a second-year in the College majoring in history.