In 2008, a Google search of the presidential campaign would direct you to news articles, op-eds, and think pieces on the political climate of the country and the worthiness of both candidates. Now, the click of a hashtag on Twitter can tell you much more: social media has taken our once factual communication and made it meme-driven. Sound bites are attached to hilarious pictures of the candidates’ faces and jokes are made about the authenticity of their hairpieces—Hillary Clinton once even took to Vine. Especially after an election like this, memes are largely what we have to look back on in the future to understand the frustrations, the fears, and the voices of our current political climate. But does the “meme-ization” of politics mean that our political discourse is taking a step back?

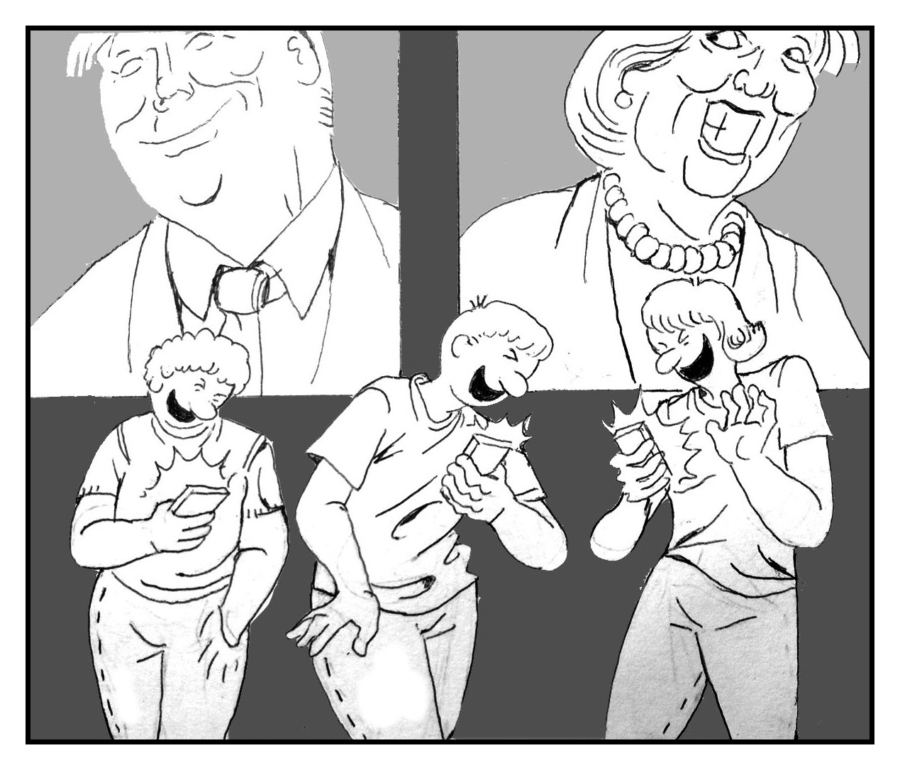

To more seasoned political analysts, that may appear to be the case. This new form of media is certainly more accessible than complex think pieces, but it escapes a large portion of the voting demographic. Particularly after the outcome of this cycle, it may have come as a shock that despite the widespread liberal consistency of political opinions in meme-culture, American voters apparently did not entirely align with the images and jokes that were circulated. Voters between the ages of 18 and 25 overwhelmingly voted blue, and since this demographic is among the most internet-savvy, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the memes circulating primarily ridiculed Trump and championed Clinton.

Let’s face it: the above-40 demographic living in rural America just weren’t the ones jumping on Twitter after a debate to caption a still of Donald Trump’s hair. As a result, the power of their vote was largely overlooked. We began to focus on what was flooding our social media, namely memes and hashtags created by the millennial generation, a generation which consistently has the lowest voter turnout. Todd Grossman, CEO of Talkwalker Americas, noted in an NPR article published on the morning of the election that “Social media may have played a role in creating a kind of scandal-driven, as opposed to an issue-driven, campaign.” The memes we created, intended to be humorous, couldn’t possibly explain the depth of a tax plan or a health care proposal—there was a forced limitation to what we could thoroughly discuss using social media and an offline demographic that was not represented.

And perhaps it may have been that we, as millennials, spent more time treating Donald Trump as a joke candidate than we did trying to grapple with and actually take down his campaign. But the question is not whether we wasted our time on GIFs and Snapchat stories: it is whether meme-culture has added anything to the political climate as a whole. Memes, in their original purpose, were never intended to replace news outlets as a source of information and detailed opinions. Rather, they were intended to reflect, in their most unedited form, a side of the political climate that could not be expressed through a news article or an episode of 60 Minutes, which serve the purpose of purely covering the issues. Memes do possibly the best job of accurately conveying what voters find to be most problematic about our candidates. This may appear, as Grossman claimed, to be a shift toward scandal-driven politics, but it is in fact an acknowledgement of what actions voters are willing to tolerate in candidates and what they are not. They reflect our inner fears, our versions of victory, and a different kind of detail: the careful attention to a candidate’s every word and action produces a significant play-by-play reaction, and a valuable commentary on campaign rhetoric. Although the rhetoric of candidates is somewhat separate from the issues they discuss, examining the way we talk about these issues gives us insight into the nature of our campaigns and of our fellow voters.

When we superimpose a crying Michael Jordan over a map of the country, it means more than retweets or notes on Tumblr: although it may appear to be oversimplified, it is one of the most accessible ways we have created to share our opinions, confusions, and fears. Memes allow anyone to add to the conversation, no matter what walk of life they come from or what information they have access to. They often escape a generation of people who do not rely as much on the internet, but this is actually a sign of the necessary power of memes: The more people join the conversation, the better and more complex our collection of voices will become.

Memes are curated by the public, for the public: What media outlet could better represent who we are, as we are in the present moment? They cannot replace an article in the newspaper, and they are not intended to. In the same way, a 1,000 word op-ed cannot replicate the raw, organic nature of the meme, and the passion that lies behind it. There is no criteria for a meme: there is no prerequisite of skill or humor, and even the internet-savviness that accompanies it is easily learned. The only thing a meme requires is awareness, and a willingness to share. Memes do give us a brief snapshot of the issues that matter to our candidates, but more importantly, memes, through their uniquely uncensored format and easy circulation, connect voters to one another in a way that can unify a country. Although it may be confusing to try and understand the outcome of this election, the “meme”-ing, so to speak, of this democracy will never change as long as the people behind it are continuing the commitment to share and engage.

Ashvini Kartik-Narayan is a first-year in the College.