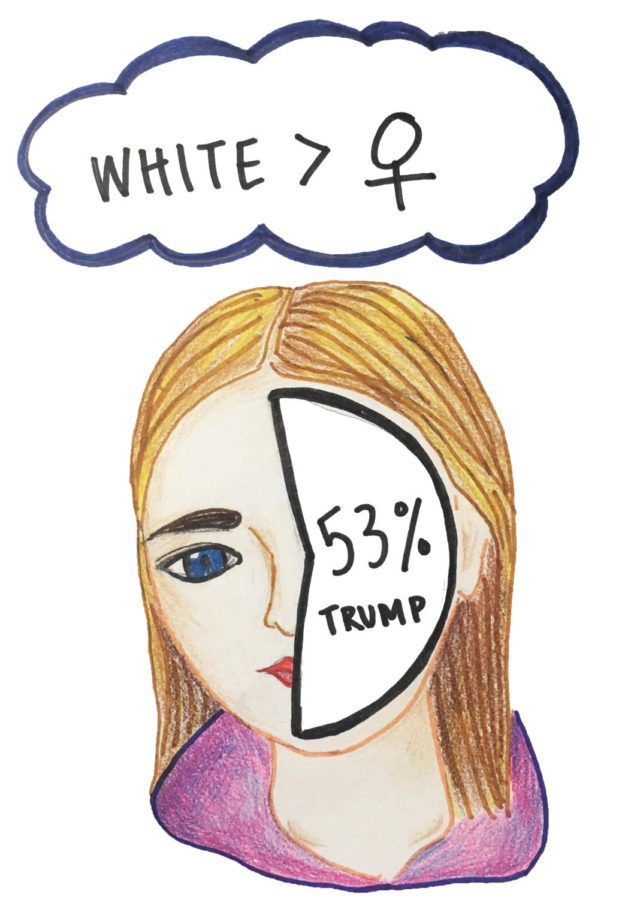

We are now living in Trump’s America. Discussions about the election and the reasons for its outcome rage on, in personal conversations as well as in the news. It has become clear that for a large part of the American public, a traditional view of identity politics does not seem to apply. Whereas voters are often defined monolithically by one aspect of their identity, people seem to give different politically salient elements of their identities different amounts of credence. For example, 53 percent of white women voted for Donald Trump. This suggests that his comments about women took a backseat to his promises that he will improve the lives of white Americans. Put more simply, white women were willing to vote based on their whiteness rather than on their gender identity.

Political campaigns often paint voters in broad strokes, oversimplifying their intersecting identities. Black people are presumed to always vote overwhelmingly for Democrats. White men vote Republican. But this kind of rhetoric underestimates the ability of politicians to truly understand their constituents. Any one person’s identity is influenced by so much more than these blunt and ineffectual identity markers. Politicians may be hard-pressed to understand intersectionality, the idea that any one person’s standing in the world is affected by the multiple categories that encapsulate their own personal history. A bisexual, white, college-educated man from an urban setting is likely to have a very different world outlook than a heterosexual white man with the same education who lives in the suburbs. Both face different issues, prejudices, and societal biases. To lump them together as simply college-educated white men reduces their differences. And yet this is how we usually try to understand the electorate.

Donald Trump was able to appeal to a large enough coalition of Midwestern and Southern voters to ensure his victory. More specifically, Trump was able to appeal to Rust Belt and working class white Americans, ensuring his victory in these crucial states. This election’s outcome was a surprise, partly because of a flawed understanding of identity politics. Pundits and pollsters were quick to assume that women were going to unilaterally vote against Trump due to his vile language about women. What they missed, however, was that white working class and suburban women were willing to accept these kinds of attacks in the hopes that Trump would build an economy with a strong manufacturing core, replete with jobs for native-born Americans rather than for foreigners. More upsetting was the constant reassurance from these pollsters and pundits that Trump’s hate-filled message would deter enough swing voters. What happened, however, is that his core message resonated with many voters who felt privileged enough to ignore his more inflammatory rhetoric. He promised to dismantle trade deals, invest in infrastructure, drive away immigrants who many blame for stealing their jobs, and ultimately return jobs to the heartland. Trump supporters did not denounce him for his hate, because he appealed to their sense of identity. His more discriminatory messages, while offensive to many marginalized communities, were not a deal-breaker for many white, working-class voters. He appealed to a group of racially privileged people, many of whom also identify as members of the disenfranchised working class.

Our collective misunderstanding of identity politics reflects a certain naiveté. We are generally optimistic about the morality of the American public, assuming that people will be turned off by hate toward other groups. But more implicitly, it is a lack of understanding of which part of someone’s identity resonates more powerfully within their consciousness. Simple demographics do not give an idea of how privileged someone is, nor does a simple gender category help us understand the way someone feels about their gender role. In order to truly comprehend the American electorate, we need to focus more on understanding the reasons people feel the way they do, beyond census-level data collection.

Perhaps the greatest evidence of the failings of this type of identity politics can be seen in the ways campaigns conduct themselves. In recent memory, the elections have come down to Ohio, Florida, and other swing states. But these states represent only a small facet of American life. The issues that plague these states are given greater credence than the issues facing states that either party deems “safe.” The issues of Northeastern states and the West Coast do not much concern the candidates since they will inevitably go to the Democrats, while the South is ignored since it always votes Republican. By catering to these unrepresentative swing states and the perceived identity of the voters within them, the interests of other states are unjustly ignored. Politicians cater to specific states and specific identities at the expense of a more nuanced concern for America as a whole. Groups of individuals with similar census data do not vote as monoliths, but rather with their various interests at heart. These interests go beyond simple data collection and speculation.

Andrew Nicotra Reilly is a third-year in the College majoring in economics and political science.