University of Chicago Urban Labs released a report on Tuesday analyzing the spike in gun violence in 2016, primarily drawing on data from the Chicago Police Department (CPD).

The report was published only days after the release of the Department of Justice (DOJ)’s year-long investigation into the CPD. The DOJ found a pattern of civil rights violations, including unconstitutional use of force and systemic officer misconduct.

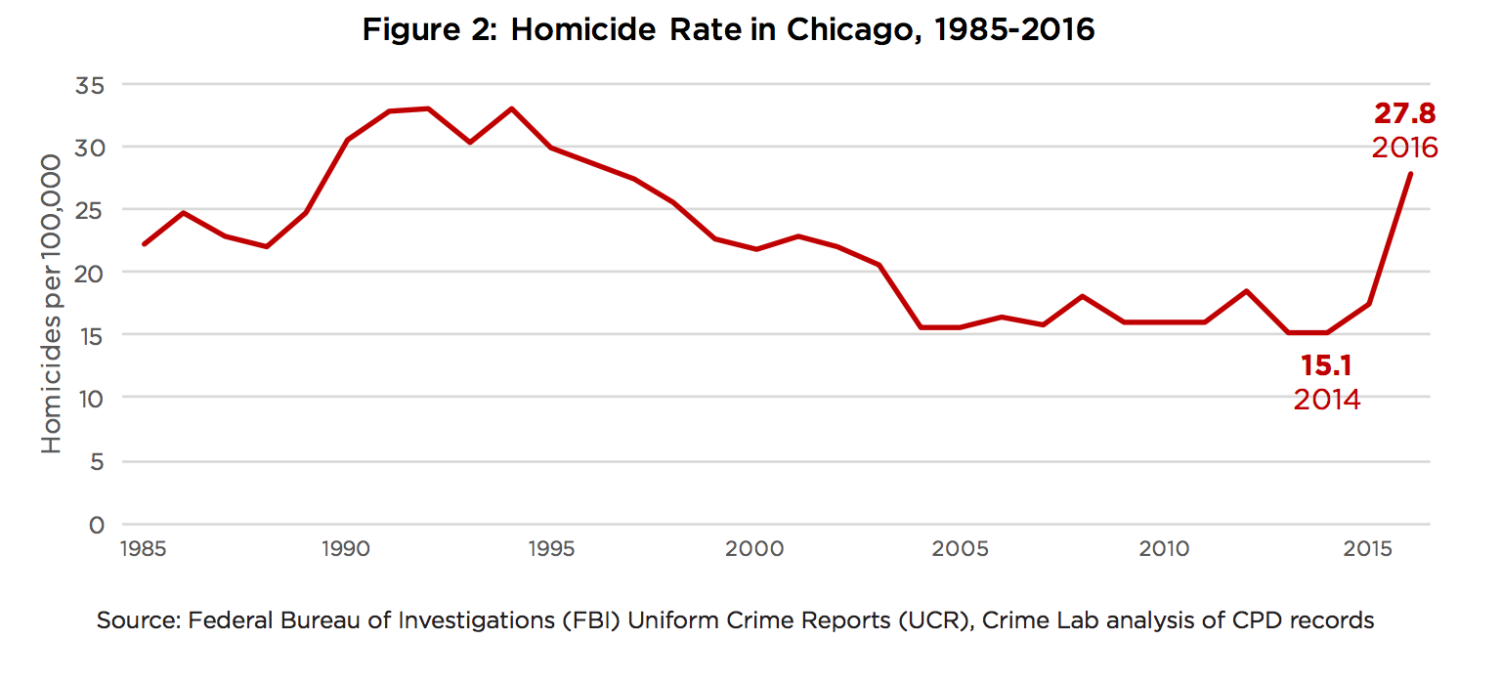

CPD recorded 764 homicides in 2016, a 58 percent increase from 2015. The homicide rate reached its recent peak in the 1990s, but declined steadily to a low of 416 deaths in 2014. However, the study found that the spike in the past two years “has eroded approximately two-thirds of the decrease Chicago experienced since the early 1990s.”

Black men continue to be disproportionately affected by gun violence. Black people make up about one-third of Chicago’s population, but comprised almost 80 percent of homicide victims in 2015 and 2016. Black men between the ages of 15 and 34 make up only four percent of the city’s population, yet accounted for half the homicide victims.

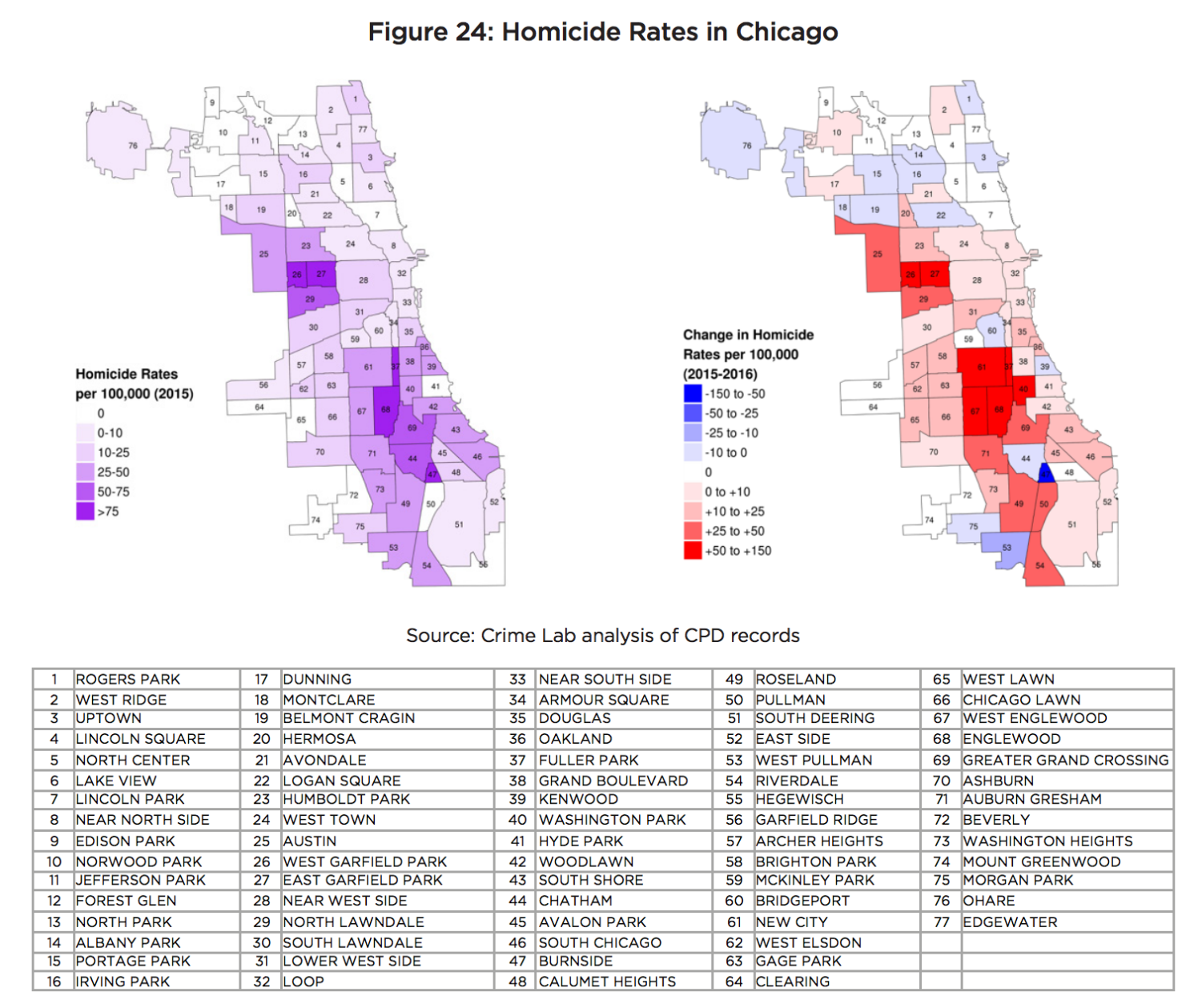

The shooting was densely concentrated in a few of Chicago’s poorest communities. A mere five neighborhoods—Austin, Englewood, New City, West Englewood and Greater Grand Crossing—accounted for almost half of the spike in violence. Of Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods, 46 experienced an increase in homicides, while 31 recorded stable or decreasing homicide rates during the city-wide surge between 2015 and 2016.

“What caused Chicago’s surge in gun violence in 2016 remains a puzzle,” the report reads. Many typical candidates to explain spikes in gun violence, including weather, city spending on social services, and public school funding, remained stable and so were ruled out as causes for the increase.

Max Kapustin, a research director at the Urban Labs, explained the difficulty of identifying a single or most important cause of the spike. He cited numerous events that occurred within a few weeks of each other in the last weeks of 2015: the release of the Laquan McDonald shooting video, the announcement of the DOJ investigation into the CPD, the enactment of a new agreement on street stops between the city and the ACLU, and a new state law regarding street stops.

The report insists that the difficulty of identifying a clear cause for the surge should not equate to a lack of response by legislators. “Not knowing the definitive cause of Chicago’s sudden and substantial increase in gun violence does not mean the city should be paralyzed in crafting a response. The solution to a problem need not be the opposite of its cause,” it reads.

Kapustin said the authors of the study were concerned that lawmakers might use the findings to justify regressive policies. “It need not be the case that you have to go back to the status quo that existed before in order to solve the problem,” he told The Maroon.

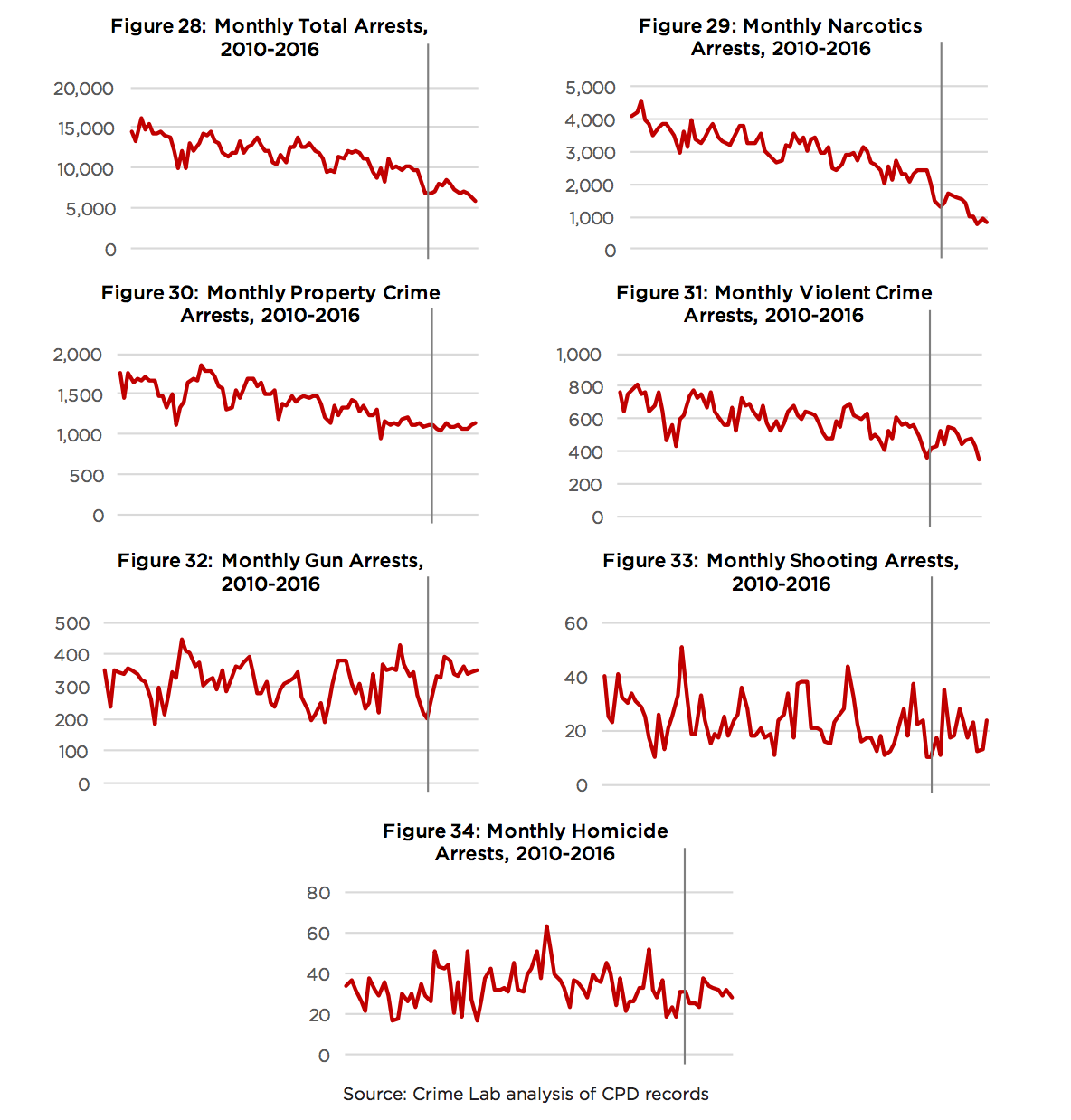

The report found that most measures of police activity remained stable between 2015 and 2016. Overall arrests declined by 24 percent, but the decline was due to in a steep fall in drug possession arrests, while arrests for homicides and shootings rose by three and four percent, respectively, and firearm possession arrests remained unchanged.

As shootings increased, the number of arrests for shootings held steady, meaning that one of the only substantial changes in police activity was a decline in the “clearance rate,” or likelihood of arrest, for gun violence. This decrease “is unlikely to have been what caused the surge in gun violence initially, but it may have accelerated this phenomenon, for example by fueling a cycle of retaliatory violence,” the report reads.

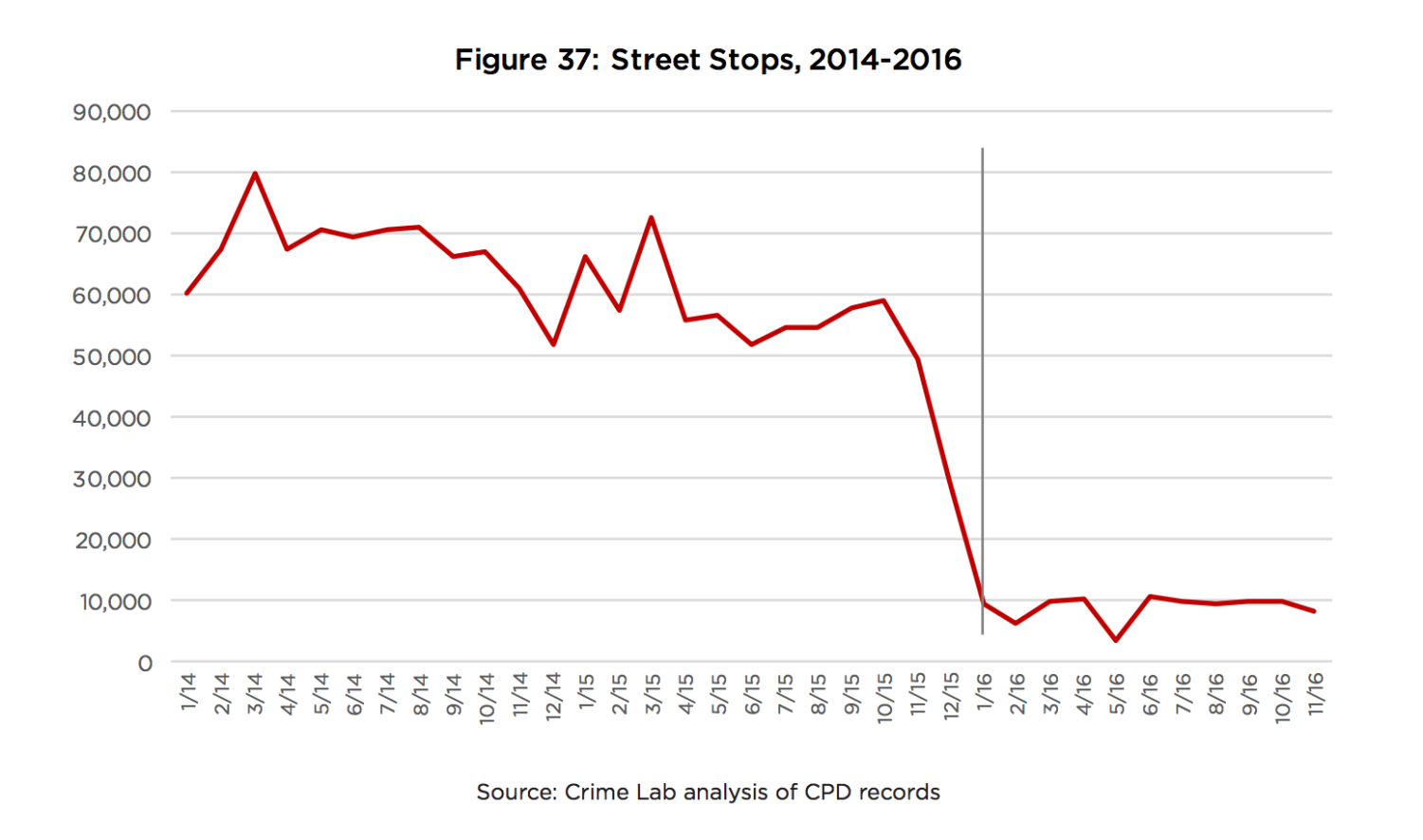

The other relevant measure of police activity that changed drastically was the frequency of police street stops, which dropped off from an average of over 50,000 stops per month in 2015 to an average of 10,000 stops per month in early 2016.

The cause of the decline is unclear, but several public figures, including former Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy and Mayor Rahm Emanuel, have suggested that increased media attention to police violence has led to officers’ being more hesitant to intervene.

“We have allowed our police department to get fetal and it is having a direct consequence,” The Washington Post quoted Emanuel saying to Attorney General Loretta Lynch. “They have pulled back…. They don’t want to be a news story themselves, they don’t want their career ended early, and it’s having an impact.”

Kapustin cautioned against trying to extrapolate too much from the street stop data. “Even though [police stops] declined quite precipitously between 2015 and 2016, and the timing fits well, other cities have seen remarkable declines in street stops, notably New York, without an increase in violence,” he said.

Lauren Speigel, a graduate student at the Harris School of Public Policy, worked on the report and said that it’s difficult to tie the sharp upswing in violence to factors that have remained relatively static in the last few years.

“When people talk about urban violence, it’s always tied to a discussion about poverty and access to services,” she said. “While those are very relevant—looking at root causes—they don’t explain what’s going on here.”

The 31-page report is available online.