“Who knew we would be here—again?” DuSable Museum Director Perri Irmer wryly remarked. A band of laughter, muted and almost sorrowful, rippled across the room. For one night only, multi-award-winning director, choreographer, and dancer Bill T. Jones had been invited to speak at the DuSable Museum of African-American History, in collaboration with the Alphawood Foundation and the new visual arts exhibition Arts AIDS America.

Yet, as Irmer noted in her opening remarks, in the context of the election and current social moment, the mood had taken on a different edge. But, it is perhaps even more so in these times—as she went on to note—that talks like these become more powerful, more poignant; it is through talks like these that we can try to come together and take “refuge in our creative institutions.”

Throughout the evening, Bill T. Jones covered a loose history of his life from the death of his partner Arnie in March of 1988 to his work with the Survivor’s Project, an organization that helps those who have survived or who are suffering from terminal illnesses. A mixture of speech, performance, and video clips, his presentation blurred a variety of artistic media together into a seamless, more abstract performance. Memory was the overarching theme, and he frequently punctured silences or pauses between acts with the simple and touching refrain “still here.” From the opening montage of his naked body being painted by Keith Haring to his opening quip—“Sorry, I don’t look like that anymore”—it’s clear that Jones has a true human interest in the dialectic between the past and present.

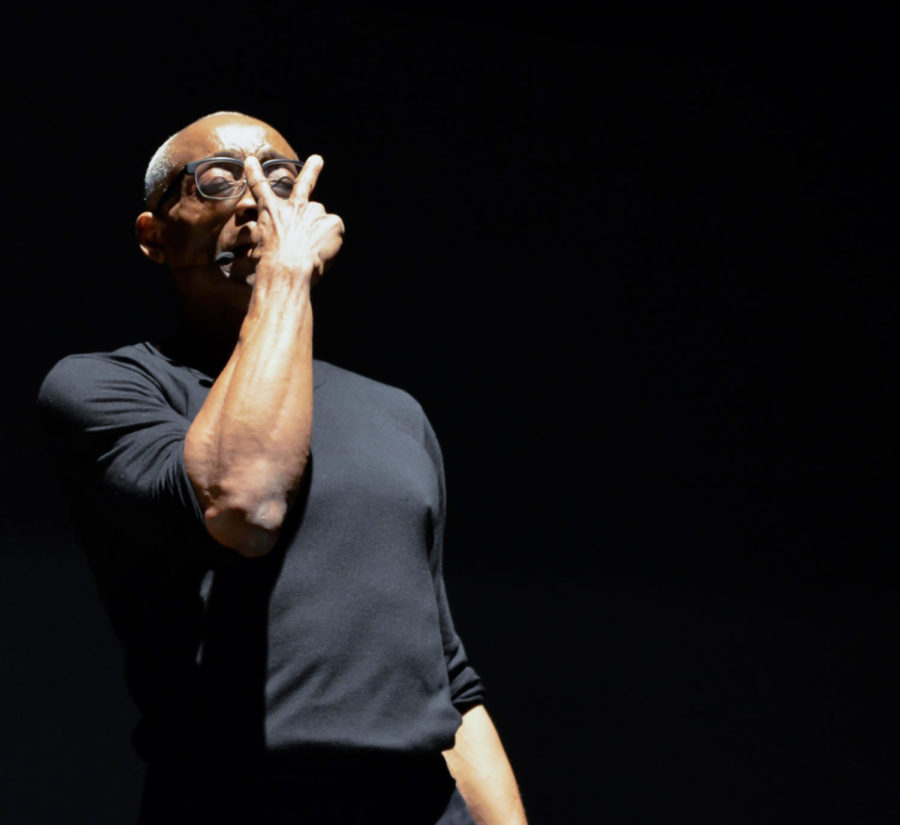

There's an almost ethereal uncertainty to displays like these that bare their hearts—scars and all—to the audience. Simply lit and elegantly designed, the stage was draped in neutral black tones with small, warm spotlights. It almost seemed to reflect the psyche of the man it was projecting on stage: With memories filled by so much sorrow, only small parts were visible at any given time as Jones tried to navigate and illuminate the larger space.

Audience members travelled through Jones’ memories, namely the harrowing, painfully detailed description of his partner’s deterioration, from their first diagnosis together (him HIV+, his partner with AIDS-Related-Complex) to his partner’s final day. This portion culminated in a performance of “Dink’s Song” accompanied by interpretive dance and a photo montage of the two of them together. In another moment, Jones paid tribute to his friend Damien with a description of the dance routine he choreographed to music by Mendelssohn. With a simple performance ‘my memory is not my enemy…my memory is my enemy,’ Jones reminisced that Damien once wore a tutu and combat boots during New York rush hour, and grew so weak from AIDS that he couldn’t walk or perform without Jones’ physical support. Though we can never truly understand Jones’ life and motivations, we can engage with the empathy emanating from the performance space, and we can learn the lessons that he can pass on.