With such a depressing national news cycle, it’s almost impossible to believe that anything good can happen. But, for the Prairie State, something close to a miracle occurred: an actual budget. Not a stopgap budget. Not a proposal doomed before its introduction. Not a list of impossibly partisan demands. A real, feasible proposal that just might pass. But we shouldn’t get too excited just yet. A budget will do little to save the state’s financial crisis unless it takes steps to address our disastrous pension system.

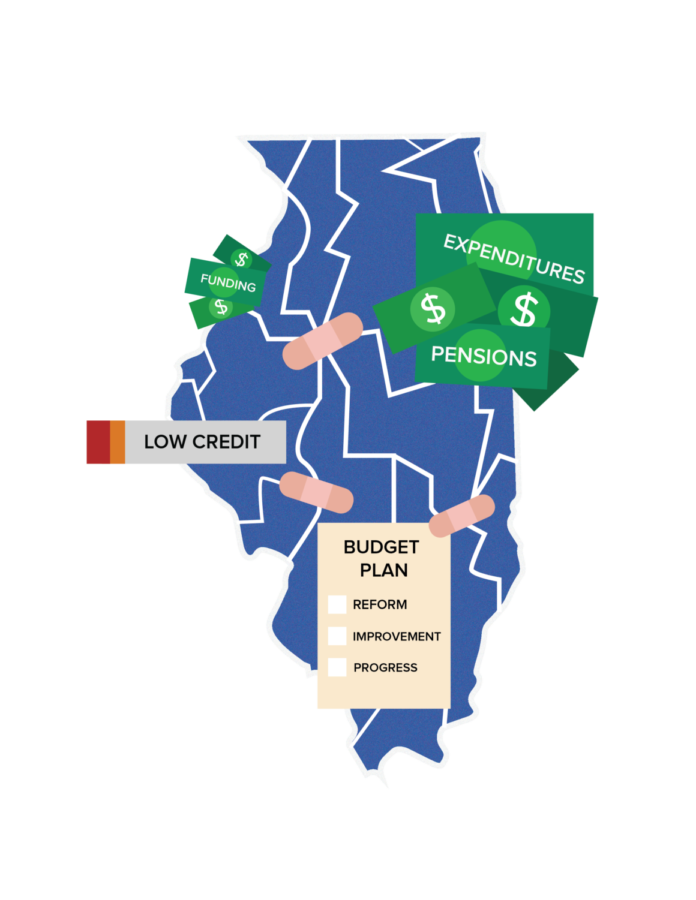

Illinois hasn’t had a budget since 2015, and hasn’t done much to work towards making one. The impasse has been long, embarrassing, and grievously toxic. Illinois’ credit rating has sagged toward junk, vendors have gone unpaid, the state’s “Rainy Day Fund” has been virtually drained, and citizens have lost what little faith they had in state government.

But most of the damage has been indirect. State universities laid off staff. Non-profits, like Metropolitan Family Services, have had to cancel critical services (including mental health programs) when the state couldn’t pay. In a historically divided country, Madigan and Rauner managed to overcome state partisanship to become equally hated by Illinoisans of all political stripes.

Finally, a proposed budget has arrived from Senate president John Cullerton. Illinois senators shouldn’t be patting themselves on the back just yet, though. A proposed budget won’t fix the disastrous pension problem we’ve gotten ourselves into. The pension is no glamorous issue. Its problems inspire little appetite for reform on either side of the aisle. Prohibitive measures in the Illinois Constitution (i.e., Article 8, Section 5) make it impossible to diminish pension benefits in any way.

But the state will buckle without reform of some kind.

Illinois’s pension system is about as bad as it could possibly get. It is, in fact, the very worst in the country, with a whopping $130 billion in unfunded pension liabilities.

How it happened isn’t an issue of contention. Illinois uses a defined benefits plan, in which recipients are promised a guaranteed amount of money per annum throughout their retirement. Employees and employers alike give a certain percentage of employee salaries to the fund on a yearly basis.

The first problem with Illinois’s pensions is that those annual contributions don’t come remotely close to covering the promised payout. As a result, taxpayers pick up most of the tab, while recipients often contribute only a tiny percentage of their payout.

Even if the pension funds were well-managed, the promised benefits would have left taxpayers with a hefty burden. But Illinois can’t manage anything well enough to save its own skin. The pensions were structured on the expectation of unrealistically high investment returns, which of course didn’t materialize. To make matters even worse, the money was compiled into a slush fund which legislators pilfered to pay for other expenditures—while often failing to make the annual contributions the funds required. (Sound criminal? It ought to be.)

The result is a bloated and underfunded set of obligations which could drag the entire state down with it. We’ve been left with a bill we can’t afford. And it isn’t shrinking. With a credit score of Baa2 from Moody’s, just two steps above junk, there’s no way for the state to borrow its way to safety, as many Illinoisans blithely assume. Since our public schools, infrastructure, and welfare programs won’t pay for themselves, we can’t allow pension benefits to consume much more of our (hypothetical) state budget. For context, it already takes up 25 percent.

The Illinois Senate can’t make that $130-billion gap vanish. The quickest fix to a crisis of this magnitude, cutting pension benefits, is both an unconstitutional and politically suicidal measure. But the legislature does have a politically viable opportunity to fix the pension’s many structural issues. It’s already demonstrated some interest; the current proposal may allow the state to offer employees a choice between a higher pensionable salary and cost-of-living raises after retirement.

That’s a start, but it isn’t enough. Fortunately, there’s room to do more: making a full budget will give Illinois the rare opportunity to consider what goes in it. Provisions to ensure that new state employees are put on defined contribution, like 401(k) plans, rather than defined benefits plans, are a must.

Pension reform has often been maligned as cold-hearted conservatism. But it should be appealing to liberals too. Ballooning unfunded liabilities aren’t abstract numbers we can afford to ignore. With pension funds sucking up increasing amounts of Illinois’s expenditures, a looming catastrophe awaits the state—one in which school funding and welfare programs for low income residents are at serious risk.

Illinois has proven itself to be incapable of responsibly managing defined benefit plans. It cannot be allowed to continue on a path of gross negligence—at the expense of not only future recipients, who have been promised vastly more than the state can give, but also of everyone who lives in Illinois. This isn’t just an issue for state employees to consider, after all. If we want to live in a state that can afford to repair its roads, operate its schools, and fund its welfare programs, then pension reform should be an issue of paramount importance to us all.

Natalie Denby is a second-year in the College majoring in public policy.