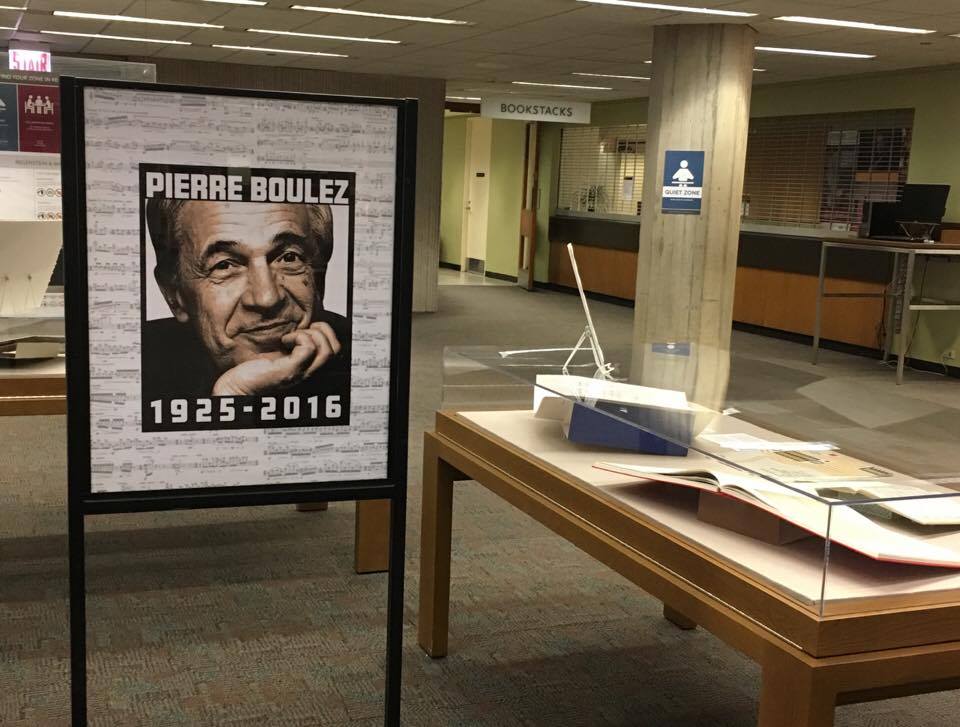

In 1952, Pierre Boulez wrote “Schoenberg is dead.” Arnold Schoenberg, the prolific composer and a founding father of atonal music, had in fact died in 1951, but his legacy was—and is—far from dead. Yet Boulez’s willingness to attack such a visionary is indicative of the audacity that made him famous. “Pierre Boulez,” an exhibit in the third-floor reading room of the Regenstein Library, commemorates the legacy of this remarkable conductor, author, and composer.

In Boulez’s obituary in The New York Times, journalist Paul Griffiths writes, “Mr. Boulez belonged to an extraordinary generation of European composers who emerged in the postwar years while still in their twenties. They started a revolution in music, and Mr. Boulez was in the front ranks.”

Born in France in 1925, Boulez began his musical career as the director of a theater company, later becoming a composer and formidable conductor. Upon his death, he was the conductor emeritus of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, had stood at the helm of such institutions as the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and the BBC Symphony Orchestra, and had gained many other accolades.

His works are considered cornerstones of postwar contemporary classical music. He engaged in numerous collaborations and projects, all the while seeking to reinvent the symphony orchestra. During his time as music director for the New York Philharmonic, he tried to institute “rug concerts,” which were performed for listeners on the floor of Philharmonic Hall, during the summer season.

The three glass cases in the Reg showcase a man who had a profound influence on classical music as a composer, writer, and maestro. They feature manuscripts of some of his most famous compositions. One case highlights Répons, a work composed for a large chamber orchestra, six percussionists, and live electronics. In the 1980s, Boulez’s repeated attempts to write music that integrated electronics and orchestral music were revolutionary.

The cases also feature two versions of Movement IV from his piece Notations, one written for piano and one for orchestra. A prominent feature of the exhibit is its emphasis on Boulez’s habit of constantly revising and rewriting his works. In another section, images of some of his early notes show one of his pre-compositional charts. The exhibition of Boulez’s infamous aforementioned 1952 essay “Schoenberg is Dead,” in which he critiques the inventiveness of the iconic Arnold Schoenberg, demonstrates Boulez’s classic polemics and support of “a radically modernist tradition,” as the exhibit explains.

Yet Boulez is perhaps best known for his conducting legacy. The two albums included in this exhibition, Boulez Conducts Boulez and Boulez Conducts Zappa, showcase his versatility on the podium. His collaboration with famed musician and genre-bending composer Frank Zappa is telling of his insatiable hunger for new musical experiences, unlikely musical combinations, and redefinition of expectations. Though celebrated for his interpretations of 20th-century works, he was also an apt interpreter of Mozart and twentieth-century repertories, and, as he matured, Mahler, Bruckner, and Strauss.

When Boulez passed away last year at the age of 90, current music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti said, “With the loss of Pierre Boulez, the world of music today is infinitely poorer.” The Reg exhibit heralds Boulez as having a “resolute imagination, force of will, and ruthless combativeness”; the cases of his manuscripts, discography, and writings allow his works to speak for themselves.

“Pierre Boulez” is an exhibition located on the third-floor reading room of the Regenstein Library.