At the tapping of a glass, the crowd in the Smart Museum looked up from their food and drinks. The man who called for their attention was Dexter Zollicoffer, who played Paedagogus in Sophocles’s Electra earlier this season at Court Theatre.

“I was sent for that purpose and will tell thee all.” With these words, Zollicoffer created a new space and time. Dressed in modern attire, he transformed the Ratner Reception Gallery into an improvised stage and the spectators into Clytemnestra’s court. The ancient battle that Orestes fought in replayed before us. Bridging the gap between past and present, his performance summed up the goal of Classicisms, the Smart Museum’s newest exhibition.

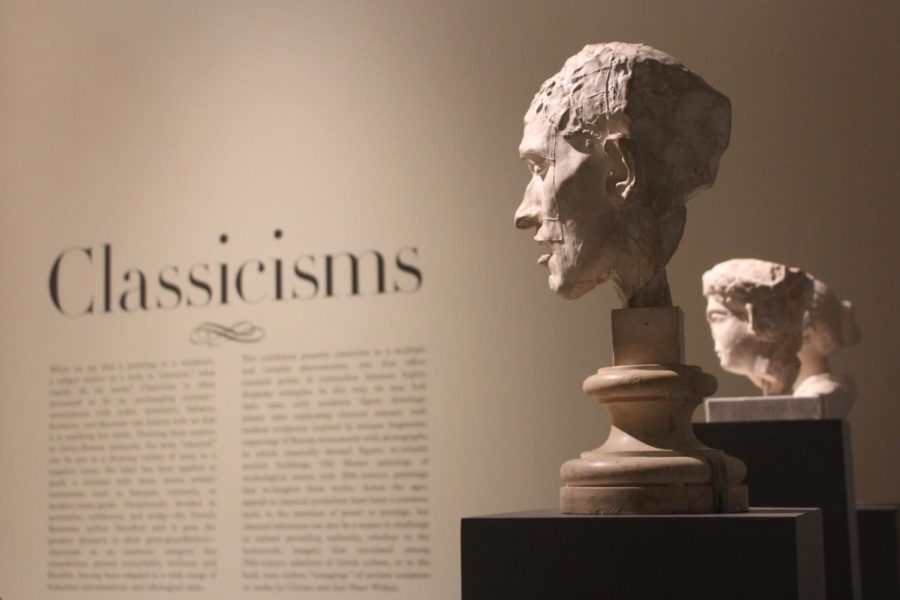

Classicisms celebrates the way visual arts have been, and continue to be, influenced by antiquity. At the exhibition’s opening reception last Wednesday, February 22, participants joined Andrei Pop, an associate professor on the Committee on Social Thoughts, and Anne Leonard, co-curator of the exhibition, for a gallery tour. Works are displayed in a nonlinear chronology: A Rodin sculpture stands next to a 5th century B.C.–artifact and an 18th-century piece. This layout allows a new definition of classicism to emerge—one centered around tension between the old and the new, between respecting and breaking the rules, between imitation and invention.

Antiquity, either celebrated or feared, appears as an endless source of inspiration for artists of the French Academy from the 18th to 20th centuries. In Giorgio de Chirico’s The Seer, antiquity appears as the shadow of an old building invading the painting, a looming menace that cuts across the frame.

Artistic Director of Court Theatre Charles Newell and Nicholas Rudall, professor emeritus of the Classics department, gave some context about Greek classical tragedy. They stated our debt to the Athenians who created an art for, and about, the city. But the question of “what the heck are we going to do now,” as Newell put it, is one of adapting this heritage to the world we live in. As the “s” in the title of the exhibition suggests, there has not been one answer to this question. Through its interdisciplinary approach, this exhibition at the Smart aims to challenge a definition of “classicism” that perhaps takes concepts of order, harmony, and decorum for granted.

In the middle of the gallery, two French paintings by William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Émile-René Ménard highlight the romanticizing of Homer as a character. He becomes the epitome of the poet. Here, as in the rest of the exhibition, the curators seem to ask the question, “How have artists interpreted antiquity throughout history, and how have they transformed it to speak to their society?”

Why does antiquity continue to fascinate both audiences and artists, even in the 21st century? In a culture obsessed with novelty, why does Newell continue to stage the ancient plays of Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus? Why do we still care about Orestes’s death?

“Because [the Greek playwrights] are talking about something bigger than family. They are talking about the big, unanswered questions,” Newell said.

They were talking about us. Still. Always.