It is almost inevitable that in their second or third year, college students will try their luck and move off campus, whether it is with Mac Properties, Peak Properties, or other real estate firms in Hyde Park. No matter the firm, they all annually raise rents, making rent prices approximately $200 more per month. But, is this increase, when considered against the backdrop of the housing market, fair for students? The answer is a little more complex than one may think. Rent increases are inevitable given that demand for apartments in Hyde Park is so high. While this may not sound fair, off-campus living costs will always be lower than those of living in the dorms.

To give a brief overview of the market to understand where we fit in, it’s essential to understand the housing market more generally. The market is cyclical and characterized by four main phases: recovery, expansion, hypersupply, and recession. Each phase has held a steady 18-year rhythm since 1800, and, currently, we are in the expansion phase. This means that because of increased demand from the recovery phase, vacancy decreases across all real estate asset classes (residential, office, retail, etc.). Occupancy begins to exceed the long-term average and as unoccupied buildings become scarce, landowners raise rents. This is the phase where the price of land reflects not just the existing state of the market but also the anticipated rent growth to come, and investors, who justify this price with the future growth, overpay. Welcome to the UChicago housing market.

Our rent increases because we make it increase. Students offer a relatively constant demand due to a large portion of the student body choosing to move off campus, which is largely a more affordable option than on-campus housing. Real estate firms, in turn, acknowledge this demand and price rent accordingly. For example, one of the more prominent firms in Hyde Park, Mac, has pushed for a renewal rate that is 3 to 6 percent higher than the former tenants’ price this year. Their reasoning, according to a Mac consultant, lies in the fact that “the price fluctuates daily based on the market and the market demand.” Does the market demand, however, actually enforce this statement?

In Chicago, the answer is no. While national home prices are anticipated to climb 3.9 percent, the 2017 housing market in the Chicago area is expected to be the weakest out of the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas. The prices of homes throughout the Chicago metropolitan area are expected to climb only just 1.95 percent, which is less than what these firms are expecting from us. According to the S&P Core Logic Case-Shiller Index, Chicago’s home prices on average remain about 20 percent below July 2007 levels; it is still one of the slowest areas to recover from the housing market crash. Why is our rent rising at a higher rate than the economic trend of Chicago?

At UChicago—as much as we don’t want to admit it—the rent aligns with the demographic and economic trends of the area. Gentrification, especially in Hyde Park, has spawned steep rent increases. In the case of demographics, millennials have pushed up the number of renters under the age of 30 by nearly one million over the past decade. In response to record growth in demand, vacancy rates have fallen sharply in markets across the country and the rental housing stock in turn has expanded by approximately 8.2 million units in a decade, from 2005 to 2015. Our overpayment originates from us as students creating a high demand for apartments and, in turn, creating a micro-gentrified and luxurious economy within the greater landscape of Hyde Park, where buildings such as Vue 53 are constructed and ask from us a high rent price of $2,300 per month for a two-bedroom, two-bathroom apartment.

Pushing this discussion even further, I think another conspicuous question should be answered: is it worth living off campus even with the price increase? Nominal price-wise, let’s do a simple calculation. Assume a typical quarter has three months. Tom is a second-year living in a double in Max Palevsky and is on the unlimited meal plan. His utilities are budgeted in the cost of his room. Taking the quarterly cost and dividing by three, he will pay $920 for his room and $667 for his meal plan per month. His total cost per month comes to $1,587.

Take Beverly. She is a third-year living in a median-priced off-campus apartment. Her utilities are not included, and she has to buy her own groceries for her meals. Per month, she will pay $750 for her apartment, $20 for utilities (including water), $10 for Wi-Fi, and $259.10 for groceries. Her total cost per month comes to $1,039.

Even with a renewal rate that is 3 to 6 percent higher than the original price factored into her apartment cost, Beverly will still spend $347—$548 less than Tom per month. This allots to $3,123 to $4,932 of savings per school year.

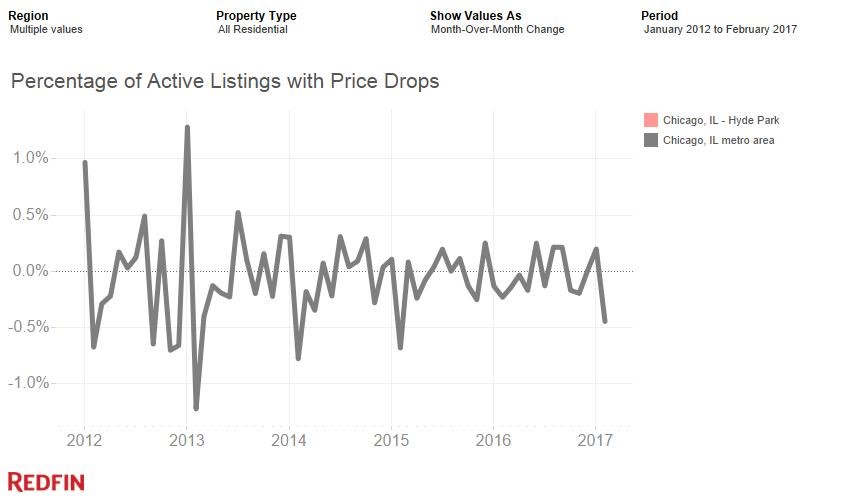

Off-campus housing, economically, is therefore more efficient than on-campus housing. Following this, I took a look at the percentage of active listings with price drops in the Chicago metro area from January 2012 to February of this year to see if there was a pattern. From the chart above, the cyclical nature summarizes the best and worst months to buy. Best months are February, May, July and October, due to a historical 0.2 percent month-over-month decrease in price. Worst months are September and January due to a historical 0.2 percent month-over-month increase in price. This is neither absolute nor consistent, but it illuminates a hope that while the housing market can be fierce, it is not without reason. Fair or not, increases in rent are impossible to avoid, but it is possible to mitigate the brunt of its impact.

Jasmine Wu is a second-year in the College majoring in economics and philosophy.