The Free Women’s Library began in New York City two years ago, when Ola Ronke started organizing monthly pop-up libraries across Brooklyn. Fueled by book donations, the libraries aim to provide free books written by and for black women.

“The library uses books to build community,” Ronke explains on her Tumblr, “and explore the intersections of race, class, culture and gender while creating a space to center and celebrate the voices of Black women and girls in literature.”

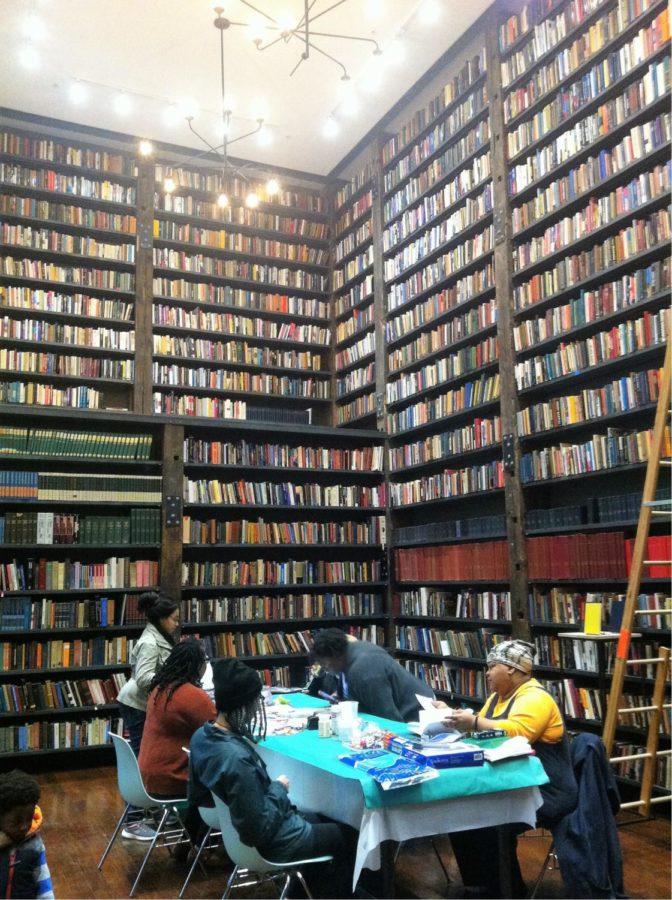

The idea quickly spread. Last year, the Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture gave away free books and organized a day of teach-ins on black women’s movements. This year, the project took place at the Stony Island Arts Bank, a national historical landmark since 2015. On Saturday, May 6, the bank hosted Chicago's second Free Black Women’s Library pop-up library—a powerful idea sown in an uncommon and vibrant place.

The bank—constructed in 1923 and abandoned in the ’80s—has been completely redesigned as a center celebrating African-American culture and history. It is an incredible space that spans the old and the new, preserving the past in a modern form. Upon stepping under the library's domed ceiling, you discover a wooden sanctuary dedicated to Frankie Knuckles, known as the “godfather of house [music].” His entire vinyl collection is stored on the third floor of the building, in what used to be a banker’s office. From the hall, you can also catch a glimpse of the impressive archival collection owned by the Johnson Publishing Company, the largest black-owned publishing firm in the United States. The bank also hosts Edward J. Williams’s 4,000 mass culture artifacts, which present a stereotypical image of the African-American community. Thus, a single building on 68th Street documents both the heavy past and the hopeful accomplishments of the black community.

The Free Black Women’s Pop-up Library thus joins in the building’s mission to preserve black culture—with an added emphasis on women. The library spread out beneath the entrance hall, with new and used books from African or African-American authors. But the books were only one part of this curious library. The entire building was filled with teach-ins, healing sessions, and arts and crafts workshops, all of which created a space where black women could feel welcome, share their experiences, and feel proud of their identity. The left wing of the arcade hosted associations working for black women's rights, such as Sista Afya, which is dedicated to black women’s mental wellness.

As a white woman, I could only partially relate to their experience, but I felt more aware of their reality, especially after the teach-in on domestic violence and criminalization of black women taught by Deana Lewis, a member of the association Love and Protect. Through brainstorming and collective writing, the session offered a moment to reflect on what it means to be a black woman today among the images the media and society convey. The group of women in the room discussed their experiences with the criminalization of black people, particularly women, in schools and on the streets.

The discussion was followed by a presentation on the trial of Bresha Meadows, a 15-year-old girl arrested for killing her abusive father. Love and Protect is actively seeking her freedom, denouncing the injustice of her situation.

“She has been in jail for almost a year now,” Lewis said, “because no one else defended her and her family against domestic violence. Her health, both physical and mental, is not taken into account. She needs to be healed, not punished!” The participants were given the opportunity to write a note to Meadow herself as well as to her judge to plead for her release.

In a building that houses the hope and weight of African-American history, the pop-up library represented the multiple aspects of black women’s reality: It was both joyful and solemn, celebrating a community gathered to remember its heritage, accomplishments, and struggles.