Led by Slovak conductor Juraj Valčuha, Thursday’s program at the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) was like a walk past the pastry counter of a Viennese café—each item sweeter and more decadent than the last.

The association isn’t purely sensory: The evening included works by Haydn and Johann Strauss, Jr., composers strongly associated with the Austrian capital, plus the waltzing-and-stomping Der Rosenkavalier Suite, drawn from Richard Strauss’s opera also set in Vienna. The apparent outlier, Polish composer Karol Szymanowski’s Violin Concerto No. 1, was nonetheless right at home in this lush, effusive program.

The evening began with one of Haydn’s Paris symphonies, the grand No. 85, nicknamed “The Queen” after Marie Antoinette’s supposed fondness for the piece. The symphony reflects a conscious synthesis of French musical convention, from the dotted rhythms in its first movement’s broadly striding introduction to the French folk song that forms the basis of the Allegretto second movement. But through and through, this symphony is quintessentially Haydn, and the CSO played with all the brightness, transparency, and clarity such a work requires.

The only thing missing? Some of the irreverent dynamic contrasts—so essential to Haydn—might have been more pointedly wrought without boiling over into caricature. On the whole, however, Valčuha’s clear-eyed vision for this 20-minute symphony helped even a very repetitive piece feel mobile and fresh.

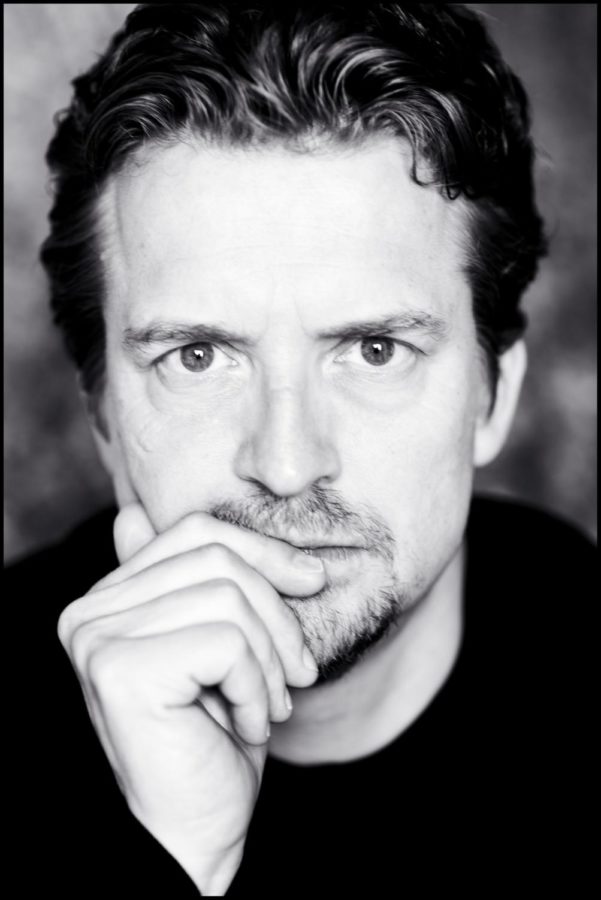

German soloist Christian Tetzlaff stepped into the spotlight for what was easily an evening highlight, giving a virile interpretation of the relatively unfamiliar Szymanowski. Tetzlaff has long been an advocate for Szymanowski’s overlooked concerto—a one-movement, richly harmonic, polyglot masterwork—having recorded the piece with Pierre Boulez and the Vienna Philharmonic in 2010 for record label Deutsche Grammophone, and he spoke passionately about the work in a video posted to the CSO’s website.

That passion came through in spades during Thursday’s performance; it was obvious that Tetzlaff truly immersed himself in this work. Although he performed with sheet music, he rarely consulted it, and gave a performance that was deeply personal and thorough without feeling studied. Though it seems clichéd when discussing artists of this caliber, one got the sense Tetzlaff could do anything with his violin: his intonation was unimpeachable, his sound big and bold, his fingers agile. All of this was tossed off with a natural ease that made even the piece’s most demanding passages look like child’s play.

The many ovations that called Tetzlaff back to the stage were well deserved, and the Szymanowski is due another hearing in Chicago, hopefully sooner rather than later.

The same royal theme from Haydn returned with Strauss’s Emperor Waltz and opened with a similarly majestic promenade, this time military in flavor. (The cut-time introduction is often snipped out of “Best Of” CDs, which—to the detriment of the piece—prefer to cut right to the first sentimental waltz theme.) Wisely avoiding kitsch and frivolity, Valčuha led the piece with the same dignity and attention to detail as the other pieces on the program, and the CSO responded with affectionate warmth, though one wonders why this rousing waltz didn’t open the program.

The waltzes in the Rosenkavalier Suite which followed presented the Viennese waltz at its most self-referential, as only an outsider could render. A Bavarian, Richard Strauss (no relation to Johann) was met with a mixed reception in conservative Vienna, and the rowdy edge to his saccharine waltzes from Rosenkavalier betrays an ironic take on the Viennese high society of yesteryear. (This milieu was also captured 10 years later by Ravel’s La valse, which similarly aches of toothrot.)

Richard Strauss and the CSO tend to pair well, and Thursday was no exception. Valiantly sung out in unison, the opening horn call was gooseflesh-inducing, the harmonies in the strings so plush you felt as though you could sink two feet into them.

But the real standout, yet again, was Valčuha. Recently appointed music director of the esteemed Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, it was no wonder he conducted the suite with an eye toward its operatic source material. Rather than resigning to the suite’s inherently episodic structure, Valčuha managed to tie all the goodness together into a multilayered cake, streamlining the scenes into a robust miniature of its own. It was a delicious end to an already memorable evening.