This article was based on a set of internal administration documents given to The Maroon last month. More information on these documents can be found here.

Unaudited budgetary documents obtained by The Maroon provide an unprecedented and extensive look at the University’s current financial state.

The documents include a fiscal year (FY) 2017 budget update presented to the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees, a third quarter budget progress report of the same year, and a preliminary list of points of concern and upside potential for the FY 2018 budget.

University administrators pushed back against much of the contents of the “inappropriately obtained” documents in a statement provided to The Maroon, arguing that the numbers in the files reflect only a “moment in time” and do not “take into account major factors such as revenue from fundraising for the endowment, investment returns, and patient revenue from the medical center,” making them “incomplete.”

The documents, likely drafted by the Provost’s office, show that the University’s operating expenses have exceeded operating revenues by millions of dollars in FY 2017, even with delays to the start of several major capital projects, such as the Rubenstein Forum, until the next fiscal year.

While they did not deny that the numbers showed that the University ended the fiscal year with an operating deficit, administrators noted to The Maroon that “the University’s financial plan included a certain number of years of Board-approved, planned deficits” to “maintain and enhance its eminence.”

This disparity between expenses and revenues partially appears to be the result of several units failing to meet their assigned budget targets. The acquired budget progress report suggests that several units may have missed their targets due to a variety of issues, such as unexpected declines in gift revenues, a reduced number of prospective student campus visits, and a state budget crisis.

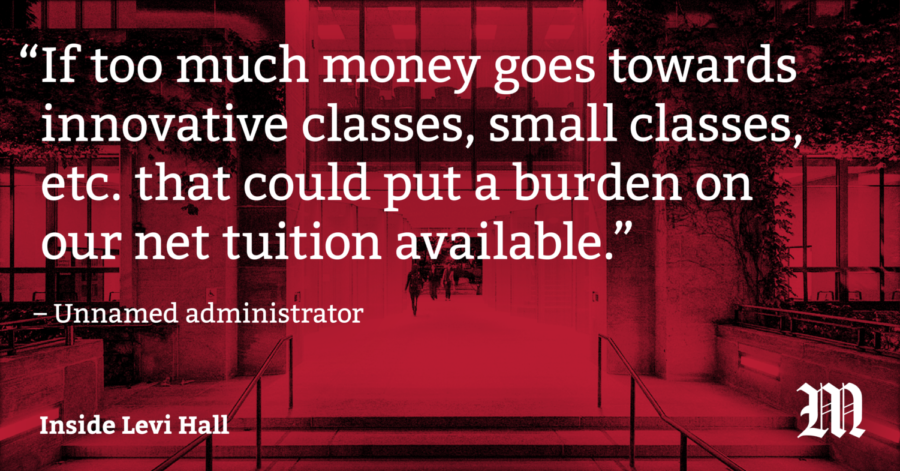

In the set of notes on the FY 2018 budget, an unnamed administrator familiar with the University’s budget situation, in an effort to maintain fiscal discipline, warns against “too much money go[ing] toward innovative, smaller classes, etc.,” advocates in favor of establishing an internal bank, and suggests potentially exploring a process called “position control,” where some new non-faculty hires would require approval from senior administrators.

The notes on the FY 2018 budget also call the status of federal grants under President Donald Trump’s administration an “existential concern.”

The administration said, in reference to the FY 2018 budget document, that “Academic decisions, including what courses are offered, are made solely by deans in consultation with faculty members and other academic leaders. Deans have authority over academic direction and resource allocation within their schools or divisions. An undated and unsigned document of informal notes does not constitute University policy, and it is not representative of programming and budget decisions within units.”

The documents are attached in full at the bottom of this story.

The documents, in context

When Daniel Diermeier succeeded Eric Isaacs as provost last July, he set out to standardize the administration’s accounting practices by adopting the widely used GAAP standard, or Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, across all units.

By ensuring that unit finances were measured by a standardized metric, the Provost could assign each unit in the University a budget target. The leaders of units are granted flexibility in determining how their units would meet these targets.

Diermeier told The Maroon at the end of spring quarter this year that budget targets allowed the University to cope with economic pressures without technically instituting “budget cuts,” as the former allowed units to compensate for budget reductions without cutting back on expenses—if they successfully earned additional revenue.

Some of the documents provided to The Maroon appear to be the product of the Provost’s new initiative. In particular, the May third quarter budget progress report reports, in table form, how close each of the University’s units were to meeting their assigned budget targets. This report does not reference the Medical Center, whose revenues are extremely significant, suggesting that it was the product of the Provost’s Budget Office, which only manages budgets for the University proper.

The FY 2018 budget notes appear to show that this new initiative, billed as a cost-saving measure by the provost, will be less than fully implemented for FY 2018, leading to a substantially larger budget overall. The document states that “Because certain units were partially exempt from…reaching their full GAAP performance target, and we have gone over our budgeted amount for central commitments, we are looking at a budget that comes to ~($95M) rather than the ($80M) target."

Factors for concern

The notes do not enumerate the units that had missed their budget targets, but the May budget progress report—which provides unit performance information absent from the University’s publicly released financial reports—provides some hints.

The progress report shows that not all units were on track to miss their performance targets. Those that were clearly off track, however, would likely fail to meet their targets for a variety of reasons according to the administration.

Several units are noted as having attracted a smaller amount of gifts than budgeted, with the Law School in particular receiving $5.9 million less than anticipated in restricted gift revenues.

Some units faced unique challenges. The University of Chicago Press struggled due to continued declines in book sales, reflecting industry trends. The Institute for Molecular Engineering faced high faculty start-up costs as the young unit continues its ambitious initiative to hire faculty. Admissions also needed more funds than budgeted in an attempt “to address concerns about [a] drop in campus visits by prospective students.” In a statement to The Maroon, however, the administration said that “Admissions has been an area of notable strength for some time, with considerable long-term improvements.”

There are also signs that the Illinois budget crisis had a negative effect on University finances. The state’s failure to pass a budget had forced CPS earlier this year to freeze funding for charter schools. The document reveals that the University had to provide additional funds to the Urban Education Institute, which runs the University’s network of charter schools, during this period to make up the gap.

The budget progress report does not describe how much the units were budgeted to begin with, and whether these budgets were lower or higher than those from previous years. Long term trends thus cannot be inferred solely based on this report.

Balancing the budget

Observing that there is no contingency (the nature of what a “contingency” entails is not specified), the FY 2018 budget notes document identifies missing budget targets as an especially important problem. The notes include details of possible methods to cut costs, some of which appear to have been scheduled to be implemented over the next fiscal year.

The document states that spending “too much money” on “innovative classes, small classes, etc. […] could put a burden on our net tuition available.” It labels such spending practices as mismanagement.

The “upsides” section notes that John W. Boyer, the Dean of the College, is expected to be “quite conservative in the use of tuition dollars.”

The administration also will introduce an internal bank that is expected to cut costs. While the exact process is not described in the obtained notes, the internal bank could allow units to save any allocated funds that they could not use to augment their budgets for the next fiscal year. With such a system, units will no longer have as strong an incentive to use up all their allocated funds within a fiscal year.

Along with the opening up of the internal bank, the document states that the University expects new deans to be more effective at reducing costs for the divisions they manage.

The document also suggests that the University could look into what is called position control to further reduce costs, identifying Columbia University as a model.

While information about position control at Columbia is not publicly available, the University of California, Berkeley introduced position control in 2016 in an effort to cut persistent budget deficits and describes it as a system in which all new staff hires (excluding student jobs) have to be approved by a top level administrator. When a staff member retires, Berkeley can, under position control, centrally determine whether the employee is worth replacing—likely lowering the number of individuals employed by the university in the long run.

There is no indication that the University of Chicago has adopted such a system for the FY 2018 budget, but it may look into such an option if deficits continue to be a problem.

Trump administration adds uncertainty

The FY 2018 budget note document mentions another significant factor that could impact the bottom line, stating that there is an “existential concern on federal grants” if the Trump administration is able to implement a substantially lower cap on federal government reimbursement rates for “Facilities & Administrative” costs.

The Facilities & Administrative cost reimbursement program (F&A) is designed to reimburse universities for some of the indirect costs involved in conducting research, such as accounting, building maintenance, and central support services like libraries. These costs are very significant, so universities negotiate with the federal government every year to determine a reimbursement rate—essentially the percentage of the total cost that will be covered by U.S. taxpayers.

Trump’s 2018 budget proposal suggested a 10 percent cap on National Institutes of Health spending that covers indirect costs for universities and other entities that receive grants for science, reasoning that many private organizations, like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, are less generous in covering these indirect costs and that a fixed cap would reduce abuse.

The document raises concern that such a cap would be financially disastrous for the University, likely due to the fact that its F&A rate for on campus research hovers around 60 percent.

The administration confirmed that it is worried about a potential F&A cap, providing The Maroon an unpublicized letter[3] that University president Robert J. Zimmer sent to Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services Tom Price and Director of the Office of Management and Budget Mick Mulvaney.

In the letter, Zimmer implores Secretary Price and Director Mulvaney to consider the “potential negative consequences” of the cap, noting that a fixed 10 percent F&A cap would reduce the “university’s annual indirect cost recovery by about $38 million.”

Ultimately, however, the University may have reason to be somewhat optimistic. Congress may oppose the F&A cap. It has recently showed few signs of supporting the executive branch’s proposed cuts to scientific funding.

How we got here

That the University, excluding the Medical Center and the Marine Biological Laboratory, has ended FY 2017 with a negative bottom line is perhaps not surprising when examining the administration’s financial strategy since 2008, two years after Zimmer became president.

Instead of cutting expenses and avoiding debt during and after the Great Recession like many peer institutions, the University did exactly the opposite.

Spurred by historic gifts like David Booth’s $300 million naming gift to the then–Graduate School of Business in 2008, the University borrowed heavily to finance a large number of construction products, costing well over $1 billion.

Administrators felt that this spending, which included a series of planned deficits, was essential to ensuring that the University maintained its status as one of the world’s elite institutions. Some have speculated that the University also saw this period of economic uncertainty as an opportunity to overtake some of its cost-cutting peers.

John Cochrane, a former professor at the Booth School of Business and now a senior fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, noted in a blog post in 2014 that the University had every incentive to borrow. Interest rates were historically low, so borrowing could often be more attractive than saving.

Nevertheless, heavy borrowing had consequences. In 2014, Moody’s cited its growing debt load when it downgraded the University’s credit rating (while noting that “Indications are that the university's investment in strategic priorities is yielding favorable results that will position it well in the future”). The University’s unusually high debt load relative to its comparatively smaller endowment (when compared to Harvard and Yale) was also noticed by Bloomberg and Crain’s.

In 2015, academic departments reduced their budgets by 2 percent, while non-academic units faced 6 percent cuts. In that year and the next, layoffs were not uncommon, affecting, according to Crain’s, at the very least 100 staff members.

The University managed to keep itself in the black overall between 2012 and 2016 with the help of patient revenues from the Medical Center (UCMC), which are denoted separately in fiscal year reports released by the administration.

The University’s negative bottom line this year, as suggested by the documents provided to The Maroon, appears to be a continuation of the University’s financial strategy adopted after the recession.

Despite the continued deficits, the administration told The Maroon that the University is financially healthy and remains confident in its strategy.

“The University of Chicago’s finances are sound and have continued to grow stronger in the last year. The University anticipates that record fundraising and strong investment performance in the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2017 will combine to increase the endowment to a record level for FY 2017. Our credit ratings remain in the Double-A category from all three major rating agencies, and this strong financial position will facilitate continued investment to maintain and enhance the eminence of the University,” University spokesperson Jeremy Manier wrote in a statement.

Professor Denis Hirschfeldt, the University of Chicago chapter head of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), told The Maroon that such a rosy picture can be hard to easily accept, especially when remembering recent cuts and the “secrecy and unaccountability of the Board of Trustees’ decision-making process.”

“The cuts have rightly raised suspicions, as there seems to be an uncontrolled growth in new centers and institutes, contrasting with a lack of concern and funding for the basic teaching and research missions of the university. In this issue, as in so many others, lack of transparency makes it difficult to trust the process and the thinking behind it.”