In just the past five years, the University of Chicago has expanded at dizzying speed. It broke ground in 2016 on the long-awaited and hard-won University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) trauma center and expanded emergency facilities, and announced the same year that it had successfully brought the Obama Presidential Center to the South Side. It opened Campus North and began plans for another major residence hall, and announced in March that it would provide full scholarships to the children of Chicago Public Schools employees.

These projects complement the University’s portrayal of its role as a “community anchor” for economic development, as the largest employer and a major landowner on the South Side. But while developments like the trauma center are laudable, community members are on alert to ensure that new projects make good on their promises. The mistrust stems from a long history of secretive and exclusionary housing and urban development practices by the University.

The South Side Through the 20th Century

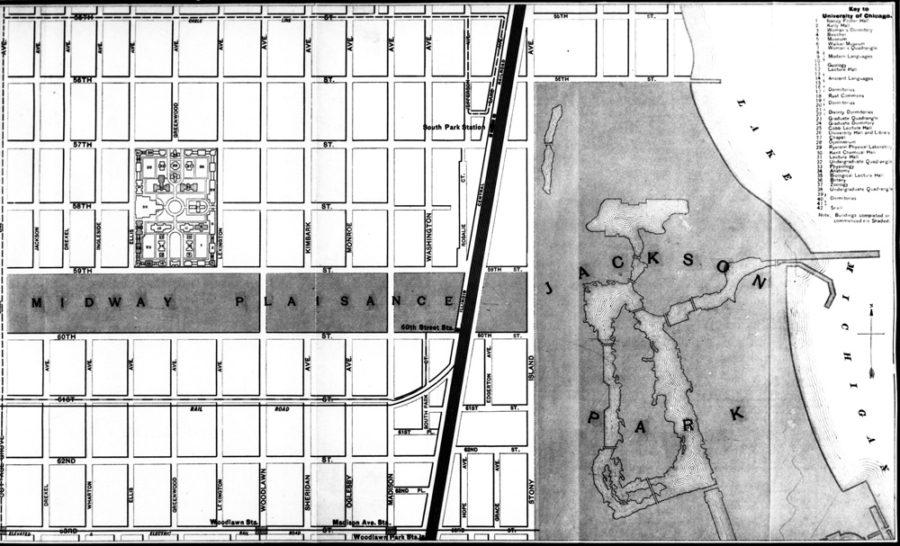

At some point while exploring the South Side’s rich offerings—catching live music or art window-shopping or trying Harold’s fried chicken—first-years inevitably notice the abundance of dead ends, one-way streets, and otherwise odd instances of urban planning at the edges of Hyde Park. The awkward layout is not an accident. Over a century of intentional restructuring built Hyde Park into an affluent haven and accounts for why so few streets run continuously through Hyde Park and into neighboring Woodlawn today.

Woodlawn sprung up as an offshoot of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair as a predominantly white middle-class neighborhood, home to many University of Chicago professors. In the early 20th century, racist housing policies kept black families confined to the so-called South Side “Black Belt,” a crowded neighborhood of low-income housing. The Back Belt was reinforced by Congress’s 1934 creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which insured private mortgages for middle-class families and became an engine for the growth of the white middle class, while it forced black families, even those better equipped to pay off a mortgage, into segregated neighborhoods.

Although redlining and housing discrimination were nationwide practices, they were by no means the only factors restricting black economic mobility around Hyde Park. Through a number of intermediary community organizations and property owners’ groups, and through its own land buying practices, the University played no small part in shaping “the white island” it occupied.

In the ’30s and ’40s, the University indirectly funded racially restrictive covenants, legally enforceable contracts to prevent selling property to non-white people, through various “community interests” projects. While the University attempted to be discreet about its real estate holdings and funding of “revitalization” projects, its influence was well-known. The Chicago Defender, Chicago’s preeminent black newspaper, reported that “many of the real estate owners in that area refer to restrictive covenants as ‘the University of Chicago Agreement to get rid of Negroes.’”

Even while the University backed racist housing practices, they led national universities in the effort to integrate and diversify academia. Unlike many of its peers, the University was founded as a coeducational school, and welcomed Julian H. Lewis, the first African-American professor at a major American research university, in 1917.

This hypocrisy extended to University president Robert Maynard Hutchins, who championed diversity within the student body while simultaneously defending racial covenants. Hutchins advocated “absolutely indiscriminate selection [admission] of students,” because “a university is supposed to do what is right, and damn the consequences.” Yet, as Arnold Hirsch reports in Making the Second Ghetto, Hutchins could not reconcile his push for diversity and inclusion with the University’s real estate policies.

Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer held in 1948 that racial covenants violated the protections of the Fourteenth Amendment, and the expansion of black communities on the South Side began in earnest, although redlining and discrimination prevented them from attaining homeownership at the same rates as white families.

In 1954, professor Julian Levi, father of Hyde Park urban renewal policies, articulated his vision of University self-interest. “We’re not a public improvement association. We’re not supposed to be a developer. We’re not interested as a good government association. The only standard you ought to apply to this is whether the University of Chicago as an academic entity requires a compatible community,” he argued to University president Lawrence Kimpton.

As the population grew after World War II, Woodlawn began to diversify, although the process was still difficult for middle-class black families. Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play, A Raisin in the Sun, documents one black family’s move to then–all-white Woodlawn, and the racial and socioeconomic tensions that result.

By the 1960s, shortly after A Raisin in the Sun was published, white flight turned the neighborhood into an almost entirely black area, centered around bustling 63rd Street, which was known for its jazz clubs. With lack of investment in the ’70s and ’80s, Woodlawn’s population plummeted from a peak of almost 81,000 in 1960 to under 25,000 in 2010. However, in the years since 2010, Woodlawn has finally seen a reversal, with population slowly creeping back up and business investment returning to the area.

In the 1960s, Woodlawn community representatives organized increasingly for bargaining power, and negotiated an agreement that the University would not build south of 61st Street. That understanding held for over five decades, but in 2016 the University presented plans for a new charter school on 63rd Street between Greenwood Avenue and University Avenue.

However, that announcement has generated less backlash than the more conspicuous dormitory plans that have followed the closing of satellite dorms. Less than a year after the opening of Campus North, the University is planning a new residence and dining complex at 61st Street and Dorchester Avenue and announced over the summer that it would make housing available in Vue53, a luxury apartment building on 53rd street.

Cosette Hampton, A.B. ’17 and current Harris School M.P.P. candidate, authored a petition arguing that University housing developments are complicit in neighborhood gentrification, and that black-owned businesses should be protected by rent stabilization.

“As University students move into Vue53 this Fall Quarter 2017 and the University makes plans to move further south to 61st & Dorchester Ave…it needs to make sure that its ‘civic engagement’ isn’t merely benefitting incoming students and professionals, but also the populations that have roots in Hyde Park and call it home,” the petition reads.

Cultural Centers: The Arts Block and Obama Presidential Library

A better-received University investment initiative is the Arts Block, which will repurpose a cluster of properties on Garfield Boulevard, west of Washington Park. The project, led by University professor and installation artist Theaster Gates, has already opened a number of arts-themed enterprises including the Currency Exchange Café and BING Art Books, and the next phase of development will develop vacant land into community green space.

By far the most widely publicized development has been the Obama Presidential Center, which has been promoted as a new kind of presidential memorial: It is intended to serve as an active community center and economic engine, bringing tourism, jobs, and extracurricular activities. Foundation chief Martin Nesbitt has spoken frankly about violence reduction as a chief priority of the community center.

But community leaders are concerned that despite its lofty intentions, the new development, with early cost estimates exceeding $600 million, could contribute to gentrification and push out longtime residents with higher prices. To prevent this disruption and guarantee that the foundation will make good on its promise to deliver jobs that pay a living wage and contract black- and female-owned businesses, numerous organizations have demanded the Foundation sign a Community Benefits Agreement. The Foundation formally refused the request this month, insisting that the agreement is unnecessary.

The Trauma Center

In 2015, while the University was lobbying heavily for the Obama library, it announced that it would build a trauma center at the medical school. Several community leaders who have long advocated for the center tied their support for the Obama library to the new emergency facilities, which have long been a source of conflict between the University and surrounding neighborhoods.

The center addresses a major discrepancy: The South Side has gone nearly 20 years without a trauma center, and as a result, victims of gun violence or blunt trauma have died in ambulance rides to distant hospitals on the west or north sides of the city. UCM’s original unsuccessful venture into trauma care closed after only two years in 1988 because of insurance issues and financial insolvency. Trauma care is notoriously hard for hospitals to finance, as trauma patients tend to be uninsured and less able to pay.

Construction on the UCM’s new $43 million trauma center and emergency room began in fall 2016. The project is tied to a wider expansion of the University’s existing medical facilities, including the addition of a cancer hospital and 188 beds, partially to accommodate an increase in trauma patients.

The new emergency room is scheduled to open January 8, 2018, and is projected to serve 2,700 patients in its first full year of operation, but that’s just the beginning; once the expansion is fully in place, UCM is expected to accommodate an additional 25,000 patient visits every year.

Housing and Community Engagement

A less publicized but highly successful development effort by the University is the Employer-Assisted Housing Program (EAHP), an initiative that provides down-payment funds to employees purchasing South Side homes. In 2014, the program pivoted from general fund support to make Woodlawn its “focus area,” and now explicitly structures loan eligibility according to its development goals: $10,000 towards Woodlawn purchases, $5,000 for other surrounding neighborhoods, and only $2,500 towards residence in Hyde Park or South Kenwood.

The University’s relationship with the South Side has also been colored by the University Community Service Center (UCSC), the network of programs founded by students and directed by Michelle Obama from 1996 to 2001. UCSC is the parent organization of numerous initiatives for community engagement, including Seeds of Justice leadership development program, the Chicago Studies program, and the Summer Links internship program.

UCSC faced backlash in 2013, when its high turnover rates and lack of transparency culminated in the unexplained dismissal of Assistant Director Trudi Langendorf. Students and program alumni argued that, under new leadership and closer University supervision, the UCSC was changing from a grassroots service network to a résumé-builder. It drew still more criticism when it added for-profit organizations to Summer Links, a social impact internship that has historically partnered students with Chicago nonprofits.

“I see this as an attempt to make this more of a pre-professional, personal growth program, which to me is antithetical to the original mission of Summer Links, which is grassroots community building,” Ione Barrows, a former Summer Links participant and College Council representative, told The Maroon at the time.

Further Reading

For further reading on the history of the University, Dean Boyer’s extensive history of the University of Chicago is a great starting place. It grew out of a series of 17 monographs delivered to faculty, one of which, entitled “A Hell of a Job Getting It Squared Around,” describes the challenges faced by University administrators Burton, Kimpton, and Levi, and their respective visions for urban renewal.

For a full account of the policies that shaped the South Side and communities surrounding your new home, see Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago, 1940–1960 by Arnold Hirsch, especially the chapter “A Neighborhood on a Hill: Hyde Park and the University of Chicago.” Additionally, Building the South Side: Urban Space and Civic Culture in Chicago, 1890–1919 by Robin Faith Bachin chronicles the earlier history of discriminatory policies at the turn of the century. Ta-Nehisi Coates’s The Case for Reparations is an excellent reference on the history of redlining.