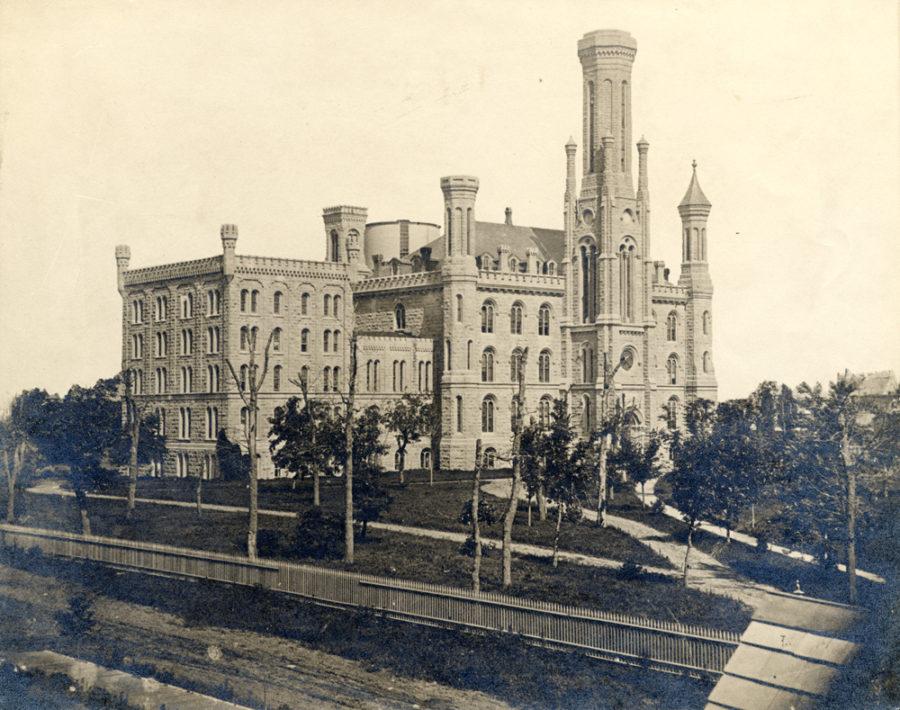

Prehistory: 1857

The first University of Chicago rose about 20 blocks north of its present campus in 1857, founded on the generosity of local Baptist congregants and land donated by Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln’s famous opponent in arguments over slavery. It lasted three decades before being done in by financial mismanagement and internal squabbling. A piece of the Old University’s long-destroyed Gothic edifice sits in the wall between Wieboldt and Classics Hall.

The New University of Chicago: 1892

Class began at the University of Chicago’s new campus in Hyde Park. Under the presidency of William Rainey Harper, it was one of the country’s first research universities, drawing from German precedents and focused on graduate education. The school was founded with support from the American Baptist Education Society, Chicago businessmen, and the oil baron John D. Rockefeller, who would continue to be a generous and instrumental contributor throughout the school’s next several decades. This combination of heady ambitions and financial windfalls established a pattern of periodic University-building projects followed by financial retrenchment.

The Hutchins College: 1942–1953

For a little more than a decade, the University of Chicago pursued a dramatic education experiment at the prompting of President Robert Maynard Hutchins. His tenure saw a rejection of traditional elements of college life seen as distractions from academic pursuits—most famously, football, along with undergraduate fraternities. He built the undergraduate experience around a prescribed, general education B.A., with specialized departmental work shifted into advanced degrees. In order to accelerate the process, the University recruited students it judged ready to take on undergraduate work as early as the end of their sophomore year of high school. For more than a decade, education at the College diverged sharply from the mainstream of American higher education. Many of the innovations introduced by Hutchins were overturned or eroded; football and fraternities both eventually returned to campus. The curricular reform, opposed from the start in some quarters, was abandoned as too radical a break.

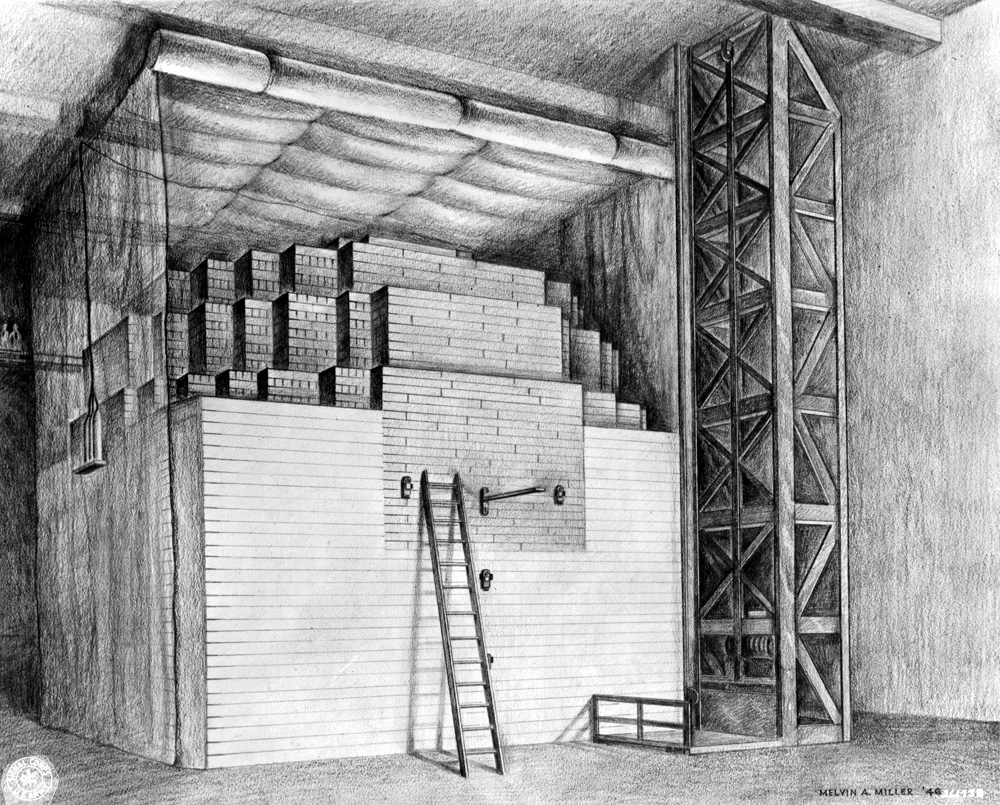

Nuclear Reaction: 1942

Seventy-five years ago on December 2, 1942, scientists working at the University of Chicago began the first artificial and self-sustaining nuclear reaction in a squash court beneath the bleachers at the now-demolished Stagg Field. (The actual reaction at Chicago Pile-1 had been meant for a rural site, away from Chicago’s population centers, but a labor dispute at the site intervened.) During the war, the University housed the Manhattan Project’s Metallurgical Laboratory as well as some of the world’s leading physicists, a key part of the United States’s effort to produce an atomic bomb. Laboratory personnel and projects sprawled across campus during the war; at one point, copies of the The Maroon containing a seemingly innocent profile of a University physicist were interdicted to avoid revealing the purpose of the project. Some members of University leadership and scientists working on the project expressed regret at the use of the destructive weapons they knew would result from their research.

Years of Rage: 1966–1969

The University of Chicago encountered the same concerted panic that faced other universities in the period. Students confronted administrators over campus housing, racism, and Vietnam. Demands for University action on the pressing public issues of the day elicited the Kalven Report in 1967, which laid out the University’s position: Its proud tradition of academic freedom could be maintained only by studied institutional neutrality.

The counter-cultural agitation culminated in the huge sit-in of 1969, which began when around 400 students seized the campus’s main administrative building 15 days earlier in protest of the decision not to rehire a popular and radical sociology professor. Disciplinary measures following the sit-in became a whole new source of agitation: At one point, a sitting of the disciplinary panel was shuffled out a side door while a phalanx of law students and security guards confronted 200 student protesters. In the end, 40 students were expelled and 82 were suspended.

A New Focus on College Life: To Present

The College’s oddness—its bookishness, its quirks of history, its monkish abstention from some traditional amenities of collegiate life—made it an odd beast. A surprising portion of alumni, one poll found, valued their education at the University but would not send their children to follow them. Admission rates, considering the University’s apparent academic rigor, were high, with correspondingly disappointing results on University rankings. The past few decades have seen a concerted effort to present a cleaner-looking university to the world. New dorms started rising around campus, and are still rising today, consolidating the old mélange of University housing into new gleaming towers and brick-orange slabs. A polished presentation of the University’s virtues has driven down acceptance rates, and the University has simultaneously risen in U.S. News & World Report. The whole process has produced no small amount of anxiety, with one graduating class after another convinced that the more recently matriculated represent an unprecedented break with the University’s history and mission.