You can’t help but wonder what the dilapidated walls of 6018North manor have seen as you weave through the wine-sipping and cheese-sampling crowd on its steps. Inside, unhinged doors and a wall traversed by a moss-like creature make you even more curious about the history of this manor-turned-contemporary-art-space that has become a performance venue for this year’s Chicago Architecture Biennial.

Last Saturday’s performance, entitled Savageness, or There are veins embraced in the property, began with its performers—Jennifer Scappettone, Judd Morrissey, and Abraham Avnisan—nowhere in sight. Hearing a rumor that the third floor of the building was haunted, the audience headed upstairs to find four pale effigies with flamboyant ribbons around their heads, suspended by strings tied to the stubs of a ceiling fan. Their spinning movement evoked the ancient Mesopotamian dance ritual that the artist Rodrigo Lara Zendejas appropriated into this artwork.

As the boundary between the art installations and the decrepit facilities of 6018North blurred, a bushy-haired dark figure, wearing a Venus of Willendorf around her neck, made her away across the hallway, breathing through a copper pipe into the electrical sockets on the walls. She wore a belt of fairy lights and a phone strapped around her forehead like a luminous third eye. All three performers emerged downstairs wearing the strange headgear, like miners about to excavate your mind.

Experimental electronica music played in the background while a light blinked on and off in a corner to rhythmically signal a pattern in Morse code. The miners stood attentively, notepads in hands, pipes to ears, to translate:

“A critical analysis would doubtless destroy the appearance of solidity of this house.”

Scappettone, Morrissey, and Avnisan took turns articulating a prophecy dooming 6018North’s “image of immobility.” They spoke of the house as a “nexus” at the center of many worlds, with invisible sprawling veins connecting it to electricity generators, stamp mills, and mines. Their performative transmission of data paid tribute to the once-vital telegraph and telephone networks that contractors and miners far from home relied on to tell bureaucratic stories about this very house.

Just outside the wall was another work hosted by the Biennial: the Chapuisat brothers’ In Wood We Trust, a convoluted wooden structure with entrances on the second floor and through a window on the first floor. Scappettone entered the shadowy shaft while Morrissey took the stairs, leaving a befuddled crowd with a glitchy recording of Bing Crosby’s “Pennies from Heaven.” Half of them followed. For those who remained, live feeds from the different miners’ headsets were projected onto the building’s walls, allowing the audience to simultaneously crawl upwards through a dark labyrinth and stand upright at its summit.

Scappettone lay supine on the platform as Morrissey poured pennies over her body for the next part of the performance, making the audience wonder whether the copper mine had collapsed upon the miner. Morrissey then began to locate the scattered currency using a metal detector. There was scarcely time for bewilderment before the next act began with all three performers taking turns in translating more Morse code. Pipe to ear, one yelled out: “PENNYWORTH DEADSHAVE!” The second deciphered: “will serve as a warning/encroaching upon the reserve.”

The performers’ code came from various code words chosen from a thick telegraphic code book filled with bizarre abbreviations and their mundane meanings. By piecing the code words together, the performers created an imagist poem that animated seemingly meaningless phrases from the past to convey a powerful statement about the environmental and social implications of urban domesticity. In the surreal space of 6018North, you could feel the taste of copper on your tongue; the fairy lights, pennies, pipes, and poetry all served to highlight how foundational the material was to the different telecommunication systems evoked in the show.

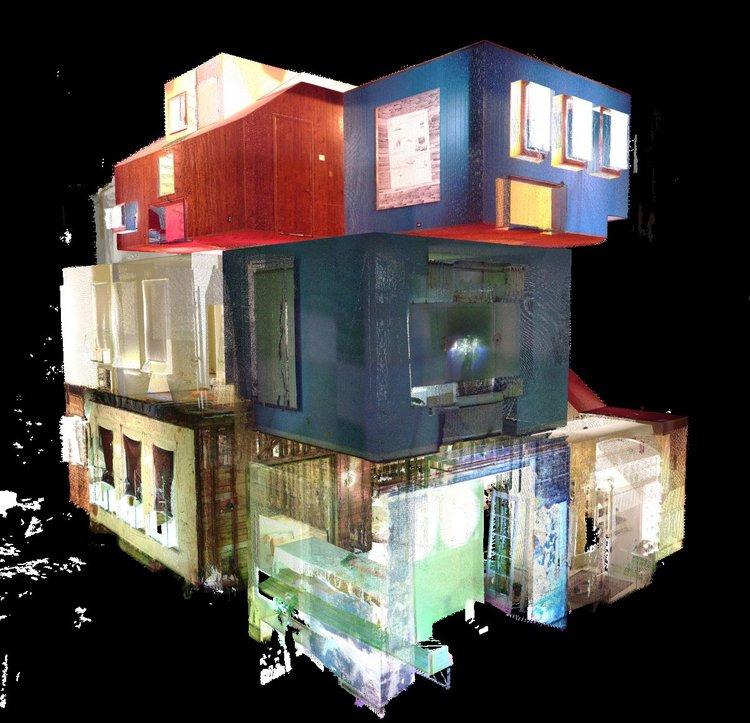

LIDAR projections formed a backdrop to the miners’ act, projecting scans that seemed to tear down the newly constructed drywall and perforate the very fabric of space-time to reveal the house’s past incarnation. Eventually, the projections were replaced by a digitally fabricated video of papers rolled up like pipes, spinning in a void, from which the performers took turns reading.

“It is impossible for a man and a family to live on 72 cents a day.” Such quotes, which ranged from personal letters to legislations, were interspersed with Crosby lyrics and more of the reappropriated telegraphic haikus, read out of an AR software installed on iPads that hung from pulleys on the ceiling. The scene could have come from a science fiction novel.

The show concluded with the three miners sitting on a dining table while Scappettone, in the middle, flipped through the telegraphic code book. Savageness gives its audience so much to take in at once that processing—let alone remembering—the experience is difficult. Yet, as Scappettone used her phone camera to let the audience see the pages of the code book, we were given a bionic eye to visualize the lives of the workers who built the very floor beneath us, who spun the wires through which people routinely upload parts of their soul, and whose work ensured there are indeed “veins embraced in the property.”