“You can see, here, she’s not worried about putting a perfect body on canvas,” said the woman standing near me at the Art Institute of Chicago.

“And the tube-like compositions,” responded her companion. “Who was doing that at this time? Léger?”

“And her name is…tar-SEEL-uh?” asked the woman. Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil is the first exhibition exclusively dedicated to the artwork of its namesake, Tarsila do Amaral, to appear in North America. The conversation I overheard between the couple illuminates the source of my anticipation for the exhibition: A complex artist whose work is worthy of deep analysis, Tarsila do Amaral—or simply “Tarsila,” as she is commonly known—is too frequently overlooked by lovers of modern art outside of Brazil. The reason is not difficult to discern: The history of modern art is often told as a narrative of innovations in Europe, even when European artists looked abroad for inspiration.

The man whose conversation I overheard is correct in that some of Tarsila’s paintings are markedly similar to those of Fernand Léger; she studied with him in Paris. Upon seeing Cubism, she remarked, “a new world unfolded to my restless soul.” Unlike Léger, however, Tarsila does not fit easily into the confines of Western modern art history. In fact, the Art Institute’s very exhibition traces the journey of her restless soul instead of constricting her to a single narrative.

Visitors to the exhibition are immediately confronted with the pinnacle of her ideological evolution: Hanging right in front of the door is “Antropofagia,” or “Anthropophagy,” which is widely considered her magnum opus.

“Antropofagia” is the literal and ideological synthesis of two prior paintings, “A Negra” (Black Woman) and “Abaporu,” both of which have been strategically displayed diagonally behind “Antropofagia” so that all three can be viewed together.

“A Negra,” notes the wall text beside it, was painted while Tarsila was still in Paris, and marks her entry into the European avant-garde. Picasso, Matisse, and countless others among these ranks had, at one time or another, also chosen a bathing woman as their subject matter. Indeed, “A Negra” seems to exemplify a phase in which Tarsila was still working with a European vocabulary: It is reminiscent of Cézanne in its creation of space through layered plains, and it exoticizes and primitivizes a non-European subject that was certainly en vogue at the time, regardless of its ethics.

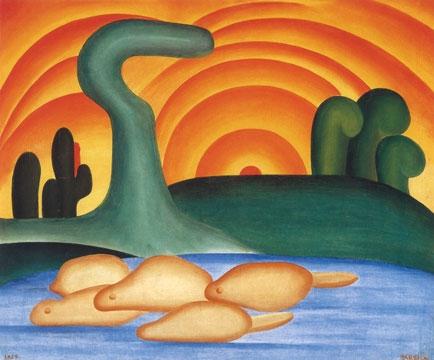

“Abaporu,” which translates roughly to “the man that eats people” in the indigenous Tupi language of Brazil, reimagines the bather through a Brazilian aesthetic vocabulary. Her work from this period often incorporates bright colors and depicts the intersection of Brazil’s natural, lush landscape and its new industrial infrastructure through the use of overlapping Cubist planes.

When Tarsila presented “Abaporu” to her husband at the time, Oswald de Andrade, as a gift, he remarked that it could inspire an entire ideology. Sure enough, his “Manifesto Antropófagu,” or “Cannibalist Manifesto,” appeared the same year, exhorting Brazilian artists to devour their myriad influences—including European—as a method for producing distinct and eclectic Brazilian art. “Tupi or not Tupi, that is the question,” quips de Andrade in a line that quite literally combines words connoting indigeneity with those of a European masterpiece.

It is perhaps to be expected, then, that Tarsila’s artwork on display from this period reaches new heights of expressiveness and beauty, as if she has been liberated from the constraints imposed by seeking a single perspective, be it European or Brazilian. “Anthropofagia” does just what de Andrade’s manifesto calls for: It combines the figure from “A Negra,” steeped in allusions to contemporary European art, with the figure, landscape, and vivid palette of “Abaporu.”

The exhibition concludes with a few of Tarsila’s later works, in which she seems to begin fusing the style of social realism, the trend among liberal-leaning artists during that period, with her own beautiful surrealism. The exhibition also includes many of her sketches and studies of form for her paintings.

Ultimately, Tarsila’s artwork and accompanying ideology would go on to inspire generations of artists. Joaquín Torres-García’s “School of the South Manifesto” in 1935 would make similar arguments about embracing local culture as a means of producing art that is contemporary and universal. The Tropicália movement in Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s explicitly embraced Tarsila’s fusion of traditional Brazilian and foreign influences. (The installation by Hélio Oiticica from which Tropicália derives its name appeared in the Art Institute earlier this year.) In a multicultural country grappling with waves of nativism and struggling to define itself, the beauty that results from Tarsila’s eclectic perspective is a lesson worth learning.

Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil will continue at the Art Institute of Chicago through January 7, 2018, before traveling to the Museum of Modern Art in New York from February 11 through June 3.