I’ll admit that I was at first a little dubious about the latest exhibition at the National Museum of Mexican Art in Pilsen, Luis Tapia: Sculpture as Sanctuary. Sculpture as sanctuary? It sounds like a caricature of vacuous “art speak.”

But from the moment viewers walk into the exhibition and find themselves confronted by Tapia’s sculpture from earlier this year, “Broken Promises,” it becomes clear that Tapia and this exhibition as a whole pose a multitude of hard-hitting questions.

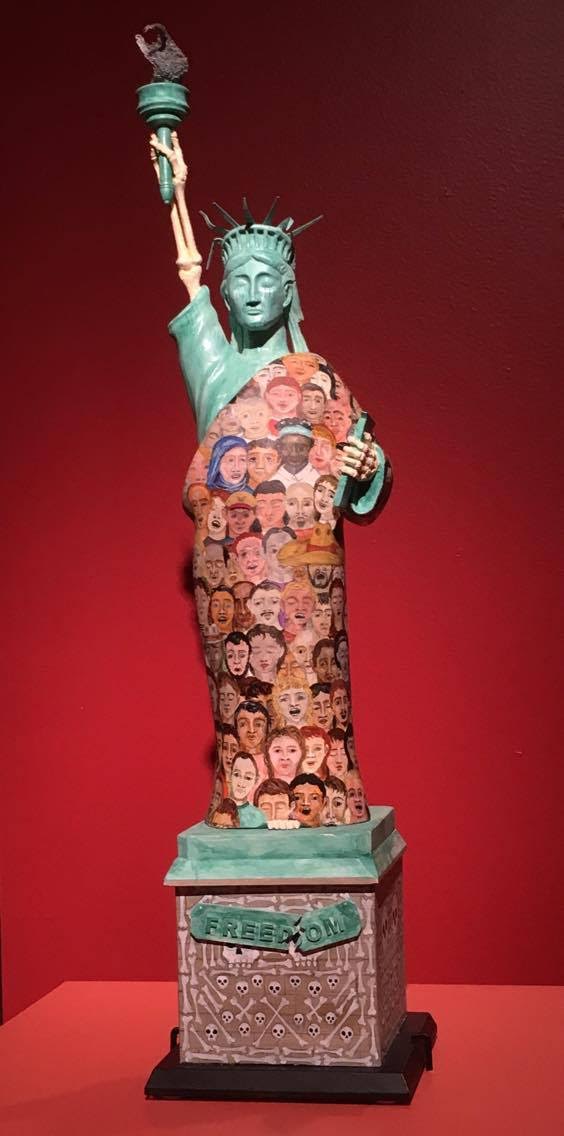

Like most of the other pieces in the exhibition, “Broken Promises” is a hand-carved and painted wooden sculpture displayed in the round. It is modeled after the Statue of Liberty in New York, but with a few clear subversions that indicate that the icon’s promise of freedom has indeed been broken. A sign reading “FREEDOM” is splintered in half on Lady Liberty’s skull-and-crossbones-emblazoned pedestal while tears run down her face and her crown wilts.

“Broken Promises” is one of a number of glaringly political pieces in Sculpture as Sanctuary. Others contrast the vulnerability, desperation, and heartbreaking humanity of the millions who attempt to cross the Mexican border into the United States alongside the severe, inhumane treatment they receive. Together with “Broken Promises,” these pieces frame the central question of the exhibition: If we can’t find sanctuary in the notion of our country and the freedom it promises, where can we?

Tapia has much to say in response to this question.

A recurring theme in Tapia’s work is the intersection of the divine and the earthly. One of his pieces, “Juan Diego,” reimagines the first American Catholic saint, granted miraculous apparitions of the Virgin Mary, as a tattooed, modern Chicano man. He holds a beer and dons a black “El Azteca Taqueria” T-shirt with an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe on it. In pieces like these, Tapia seems to be heralding the sacred significance in each individual person whom we might encounter in our day-to-day lives. His medium is itself reflective of the intersection of the lofty and the quotidian: His hand-carved sculptures continue a venerable 400-year tradition and achieve a grand level of autonomy, beauty, and meaning when displayed in the gallery. Still, they reveal the omnipresent hand of their mortal carver, as well as the recalcitrant essence of the materials from which they are made.

Proceeding from the concurrence of the sublime and the mundane, Tapia reveals that we can find moments of transcendent sanctuary in everyday life. In “Abuela,” for example, there is a palpable feeling of love and security as a young boy curiously looks up at his grandmother, whose hand he is holding. The syringes and empty bottles that litter the grungy asphalt at their feet melt away into irrelevance. On the other side of the sculpture, a rainbow separates an idyllic scene of Jesus surrounded by children and animals from a garish and overwhelming barrage of corporate logos, as if seen through the blithe imagination of a child. Another sculpture, “Dos amigos con sus vicios,” depicts two men with their arms around each other, holding beers and conversing. Tapia illustrates the potential to find sanctuary in friendship, even in the presence of external danger and violence, as implied by one of the men’s dog tags and Che Guevara shirt, and the other’s military jacket.

All of Tapia’s pieces are intensely thought-provoking. Some posit the potential to find sanctuary in one’s identity and culture, and others attack religion as a false locus of sanctuary. “Man Trapped in His Religion,” for example, illustrates a figure resigned to his gilded cage, while in “Happy Birthday, Jesus!” a confused Christ examines the weapons and consumer commodities used by people nominally devoted to Christianity.

My personal favorite piece, however, is undoubtedly “Cruising Hollywood: Homage to Magu,” one of a series of car dashboards that Tapia created. The car itself appears old, with a few personal knick-knacks, and through the windshield can be seen the bustling streets of Hollywood, along with Tapia’s friend Gilbert “Magu” Luján. The Virgin tranquilly looks on from the rearview mirror as if approving. What’s more comforting than cruising down familiar streets, in a beloved car, and spying the face of an old friend?

Reminding us of our capability to find transcendent moments of sanctuary in our everyday lives, Tapia espouses tactics, as opposed to strategy, for seeking utopia. Rather than advocating a revolutionary program to create long-term changes, Tapia seems to promote the apprehension of small pockets of joy and goodness all around us.

For many viewers, Tapia’s sculptures themselves, which create warm, intimate relationships with their viewers, might provide such pockets or sanctuaries, just as the title suggests.

Luis Tapia: Sculpture as Sanctuary will continue at the National Museum of Mexican Art through April 15.