Traversing the Past, an exhibition featuring photography by Adam Golfer, Diana Matar, and Hrvoje Slovenc, opened this Thursday at the Museum of Contemporary Photography. The three artists share family histories of political turmoil and migration, examining their countries of origin with a critical eye. The opening reception for the exhibit featured a conversation between Columbia College professor Erin McCarthy and artists Golfer and Slovenc; Matar will lecture at the college later this month.

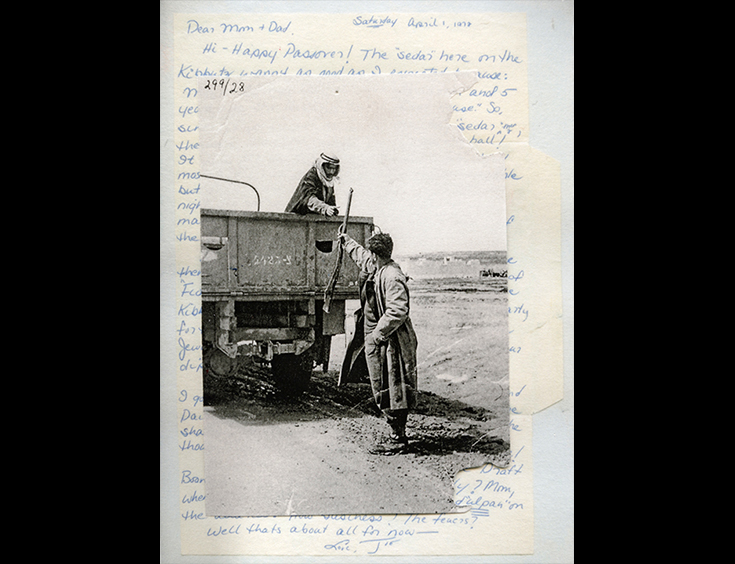

“There isn’t some sort of past that is fixed,” Golfer remarked during his conversation with Slovenc and McCarthy. The Jewish-Lithuanian artist’s work presents a look at modern-day Israel and Germany interwoven with his father’s narrative living on an Israeli kibbutz (collective agricultural community) in the ’70s and his grandfather’s experiences in World War II concentration camps. Golfer’s work is notable for its use of a variety of mediums that add additional layers of narrative to the work. His portion of the exhibit occupies multiple levels of the museum and features film, text projected with slide projectors, vintage photographs, letters from his father, and smaller printed photos nestled behind larger photographs which viewers can pick up and examine. Additionally, booklets of Golfer’s poetry and prose are available to read in the context of his other work. His writing feels separate from the rest of his work but ties in thematically as Slovenc’s collection also features his writing.

Golfer has impressively synthesized familiar iconography of Jewish identity, such as Anne Frank and Paul Newman, with imagery from his personal travels, to evoke the multiplex relationship between his own identity and the historical narrative. Screen grabs of Paul Newman and an image of Facebook recommending Anne Frank as a friend (“one mutual friend” it notes) contrast photographs of verdant hills in the German countryside and police barriers in Israel. However, knowing that those verdant hills hide residue from WWII battles and those barriers represent Israel’s complicated history with its Middle Eastern neighbors, the collection is more cohesively interpreted as a mixed-media expression of the identity crisis that many young Jews experience.

Golfer described having to fight the instinct to photograph “like a journalist” when visiting Israel, and as a result threw out lots of material that seemed too much like cliché newspaper documentation, such as photographing a weary protester holding a sign and thus forcing the weight of an entire conflict onto the image of a single person. Golfer’s collection, entitled A House Without a Roof, presents subjects of deep personal importance with an objective eye, drawing comparisons between personal history and present events, which is no small feat.

Matar’s work is concerned with the effects of state-sponsored violence in Libya. Her father-in-law, Jaballa Matar, a Libyan opposition leader, was kidnapped from his home in Cairo in 1990. The family heard from him only once, when they received a letter in his handwriting explaining he had escaped a maximum-security prison in Tripoli. He was never seen again.

The work displayed by Matar spans a variety of her projects, with photographs taken in Italy capturing the places where violence took place and imagery that represents both sides of Libya’s past. These are displayed in a more minimalist and traditional fashion than her colleagues work. Poetic inscriptions are hung side by side with some photos, adding intrigue and a touch of melancholy to the photographs. The photographs deliberately vary in size, prompting the viewer to move closer to observe some portraits, such as “Leave to Remain”, and back away to observe other larger, more abstract photos at a distance. Matar’s photography is dark, both visually and in subject matter, evoking the weariness of a people who have endured a violent civil war and the mystery of a tragic event in her own family. It was a shame that Matar did not participate in the conversation with her fellow artists, as her work and perspective would have provided for interesting conversation in context with those of Golfer and Slovenc.

“What does it mean to come home?” asked Slovenc, who is a Croatian immigrant. His part of the exhibit, a collection titled Croatian Rhapsody: Borderlands, attempts to address this question with a veritable rhapsody dedicated to Croatia. The photography is nothing touristic; the photographs represent symbols of cultural difference and display the duality of Slovenc’s personal connection and sense of disconnect with his home country.

A “rhapsody” can be a miscellaneous collection, an emotional outburst, or effusively rapturous or extravagant discourse. Slovenc’s work is all of these. The collection, which, like Golfer’s, implements multiple media to enhance the photography, is indeed a miscellaneous collection: a sensual image in inverted black and white, a triptych of abstract prints, a 15-photo series of black-and-white photographs of the backs of several men’s heads. One might describe it as “installation photography” featuring sculptural elements, a large rug representing the Croatian border, and booklets of short stories by the artist. The different elements don’t initially appear linked, in style or subject matter, but when viewed as a cohesive body of work, they provide a view of Croatia that does not want for depth or breadth.

“The more I stayed here, the more critical I was of what was happening, the more clearly I read the past,” Slovenc said.

Slovenc cleverly combines the familiarity of a native Croatian with the perspective of someone many years removed from his birthplace. The advantage of having an outsider as opposed to an insider perspective was a major topic of conversation that night, as Slovenc and Golfer both ruminated on how taking on the role of an outsider in places to which they both claim strong ties informed their photography. Golfer mirrored the sentiments of Slovenc when he remarked, “Both of us are sort of looking backwards and forwards simultaneously.”

“Photography doesn’t represent reality” Slovenc argued, but Traversing the Past is an exhibit that showcases masterpieces of perspective—works that are linked by the simultaneous affection and criticism each artist had for their subject matter—which present a truth worth consuming.

TRaversing the Past will be on display at the MOCP until April 1.