A walk through Chicago’s Andersonville is a strange experience for those of us who were not aware the city has a Swedish neighborhood, let alone one so fanatically Swedish. From the ubiquitous Swedish flag to the Swedish shops to the Swedish-American museum, it’s hard to take a step in Andersonville without being bludgeoned by Nordic-ness.

The neighborhood is quaint and the effect is cute, but the reality is Andersonville is clearly not a Swedish-only enclave. The same can be said for other neighborhoods: Ukrainian Village, Lincoln Square, and Little Italy, for instance. A great deal of the appeal that these cultural hotspots offer is strictly historical, as places that were once demarcated with clear ethnic lines, lines now seriously blurred and sanitized for visitor enjoyment.

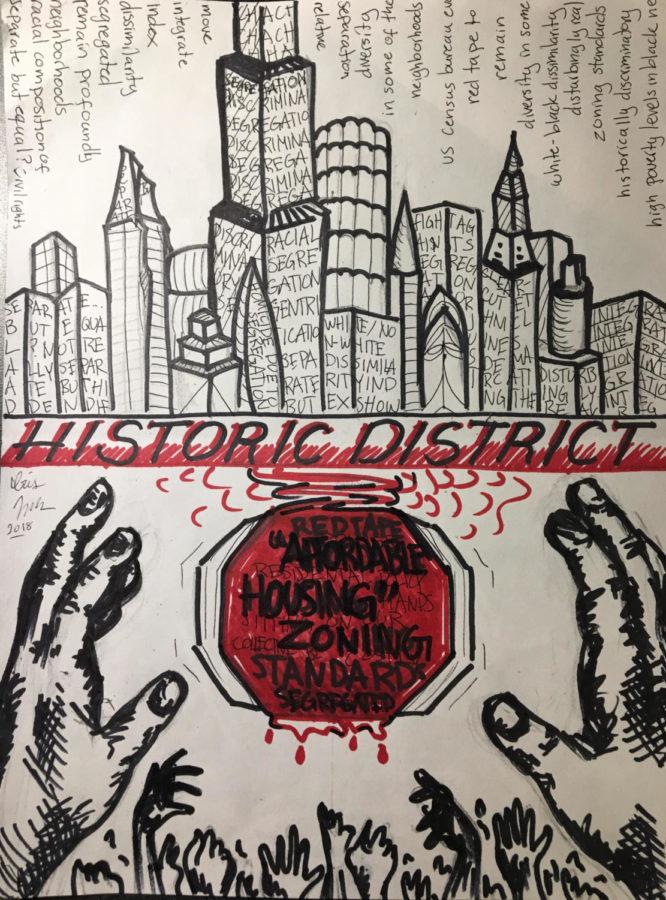

But if Chicago’s hyperspecific ethnic neighborhoods lie somewhere between historical fact and touristy gimmick, the city’s segregation between white and black is disturbingly real today.

By most rankings, Chicago is still among the most segregated metro areas in the United States. Many people, however, latch on to the city’s signs of improvement. Driven in part by movement to the suburbs, the city has become less segregated in recent years, with greater levels of diversity in some neighborhoods. The U.S. Census Bureau evaluates segregation with the dissimilarity index, used to measure the relative separation of two groups in a given area. The dissimilarity index provides the percentage of one group or the other that would need to move to completely integrate an area (a white/non-white value of 40, for instance, would mean that 40 percent of the white population or the non-white population would have to move to integrate the area). Cook County’s white/nonwhite dissimilarity index has dropped from 60 to 57.37 since 2009, an encouraging decline.

This may seem like good news, but it doesn’t tell the full story. Chicago’s white and black populations remain profoundly segregated. The white–black dissimilarity index ranks Chicago as America’s fifth most segregated metro area (after Gary, Detroit, Milwaukee–Waukesha, and New York, respectively), with a score of 83.6. That’s a stunning number, and it isn’t the only troubling segregation statistic for the city.

An alternative measure of segregation, the exposure index, shows the average racial composition of a person’s neighborhood given their race. Exposure indices for Chicago are absolutely damning. Whites in Chicago, on average, live in neighborhoods that are 78.6 percent white and only 4.5 percent black. For blacks, the average neighborhood is 14 percent white and 75 percent black—in a metro area which, by way of reference, is 58 percent white and 18.6 percent black overall. These numbers are at odds with the notion of a city making good progress in its fight against segregation, but you don’t hear them discussed very often.

Most of us are well-versed in at least two reasons for Chicago’s segregation—historically discriminatory housing policies and high poverty levels in black neighborhoods. But we tend to brush over how the city’s current residential policies exacerbate the problem. Wealthier white neighborhoods use “historic district” designations and high building standards to prevent new development and jolt housing prices upwards. Zoning standards ensure that new buildings in these neighborhoods tend to be larger and pricier. These factors work to keep these areas unaffordable, and as a consequence, segregated.

How segregation might be addressed is far from certain, but far too many are happy to simply wait for the problem to solve itself. Meanwhile, the city’s black population has been steadily declining. The cost of sitting on our collective hands is high—according to a report released by the Metropolitan Planning Council, the city would gain $4.4 billion in income and cut the homicide rate by 30 percent if it lowered the black-white segregation level to the national median. That might have been 229 lives saved in 2016.

The city has sporadically pursued measures to boost integration, typically through affordable housing efforts. But efforts to introduce this to wealthier North Side neighborhoods often meet opposition. One such measure, the Keeping the Promise ordinance, would have reformed the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA). The CHA has been running a cash surplus of over $400 million, obtained by circulating 13,500 fewer housing vouchers annually than funding provides for. Keeping the Promise would have tightened regulation of the CHA and spread affordable housing efforts across the city. After a spurt of publicity earlier in 2017, the ordinance vanished from the news, apparently set aside by the City Council to collect dust.

It shouldn’t have been. Chicago pays a tremendous price for its segregation, in terms of lost lives and opportunities. In that context, the city’s idleness is mystifying. CHA reforms, ultimately, are one of many policies that could meaningfully address the city’s segregation, but the political will doesn’t seem to exist. Many Chicagoans don’t think dramatic changes are necessary—they believe segregation is either a problem of the past or an inevitability. But segregation is preserved in no small part by today’s policies. Many others, even those of us in Hyde Park, simply don’t believe segregation has any impact on our lives. But the entire city is grievously harmed by our apathy.

Natalie Denby is a third-year in the College majoring in public policy studies.