Last Friday, the Arab Student Association invited New Orleans–and Marrakesh-based contemporary artist Alia Ali to give a talk on her multimedia practice and artistic roots. Ali started out as a documentarist and photographer before traveling extensively, gradually cultivating her interest in textile as a narrative medium. Now, Ali is best known for her work with textiles, through which she examines the politics of identity and boundary.

Ali began her presentation with a video she filmed in 2009 in Yemen, capturing the inner alleys and bustling marketplace of the neighborhood where she grew up. The site is now in ruins, razed by warfare. When introducing herself, Ali thus often references her origins in “two countries that no longer exist: Yugoslavia and South Yemen.” Growing up, she lived in a house divided between the European sensibilities of her Bosnian mother and the Yemeni customs of her father, allowing her to cross the cultural boundaries between the two. However, she soon came to realize that such borders were heavily guarded. She saw how people were valued differently when her father announced their family had not been put on the government-issued evacuation list during the violence of an early 1990s Yemeni unification, and she expressed a sense of having her soul stolen following her father’s decree that their family would no longer use Arabic after moving to America post-9/11.

As such, Ali was no stranger to the concepts of exclusion and power imbalance when she was invited to contribute to the exhibit Shades of Inclusion in Boston three years ago. She responded with a photographic series called "CAST NO EVIL,” framed also as a dialectical investigation.

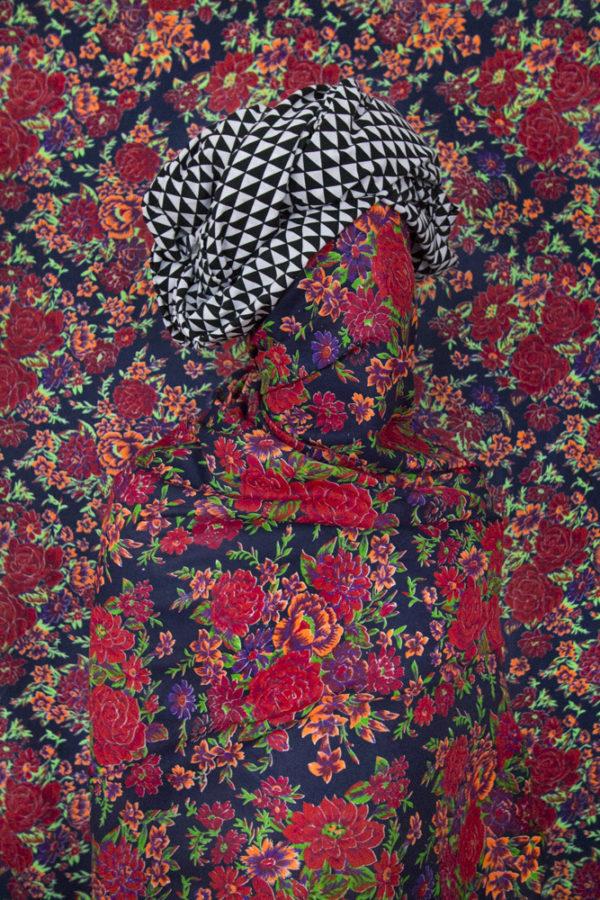

At last Friday’s talk, Ali discussed the ubiquity of the veil as a cultural marker and source of ambiguity. She explained how the garment could be a statement of devotion, sign of oppression, or expression of power. “CAST NO EVIL” took this uncertainty to its extreme, featuring faceless, fully veiled figures to expose the fabricated nature of social barriers. Ali’s exhibit asks: “[Are the figures] powerful for their anonymity or are we for their confinement?” The pieces are meant to engage viewers in an active dialogue concerning their position with regard to that fabric.

Another project of Ali’s from the same year examines her immigrant status. As an adolescent immigrant only faintly acquainted with the idea of extraterrestrial life, Ali had trouble grasping why her parents sought naturalization from a people that labelled them “aliens.” Her 2015 project, “I Am [Not],” creates otherworldly creatures out of traditional textiles partly supplanted with woven newspaper. The project embodies the tension between stereotype and personal truth by considering traditional and modern approaches to textile. “I Am [Not]” is part of a touring exhibition of art created by 31 women from North Africa and West Asia, all responding to the title “I Am.” Ali responds by studying what one is not. In her case, she is culturally a Muslim and legally an American; she is neither a terrorist nor an alien. As both the photographer and the photographed, Ali questions whether it is the individual or their media representations that hold power over their identity.

Ali’s conversation with the audience shifted toward the darker truths of terrorism and imperialism. Two pictures from “Election” (2015), created after Ali relocated from Marrakesh to New Orleans, featured figures donned in black-and-white bandanas that had been sewn into hoods reminiscent at once of the KKK uniform and the cap that Ali Shallal al-Qaisi wore in a controversial 2004 image of his torture in Abu Ghraib prison. The bandanas underscore a hidden history of American colonialism: While often interpreted as a product of the glorified Wild West, the bandana is a misappropriation of Native American visual culture and Kashmir fabric production.

In a 2016 project called “People of Pattern,” Ali traveled the world to document and try her hand at indigenous textile production, revealing the beauty ingrained in techniques from Southeast Asian floral dyeing to West African wax printing. She wanted to translate her physical border crossings into artistic ones that would encourage viewers to shed their own misconceptions about the racial, cultural, and religious borders; in particular, she wanted to counter the discriminatory attitudes propagated by certain United States presidential candidates. In every location she visited, she collaborated with locals to host free exhibitions, artist talks, and interactive workshops.

Something as perennial as textile is often taken for granted—as are people’s assumptions, biases, and misconceptions. Alia Ali’s work allows viewers to appreciate the intricacy of fabric as well as the complexity of the cultures behind them. Her sartorial aesthetic destabilizes one’s position in relation to the artificial boundaries created between cultures, languages, ethnicities, and, on the most fundamental level, people.