An eager yet unimpressive Tutorial Studies student managed to convince a dean to let him have one more read on his senior paper after his two assigned faculty reviewers chose not to recommend it for honors.

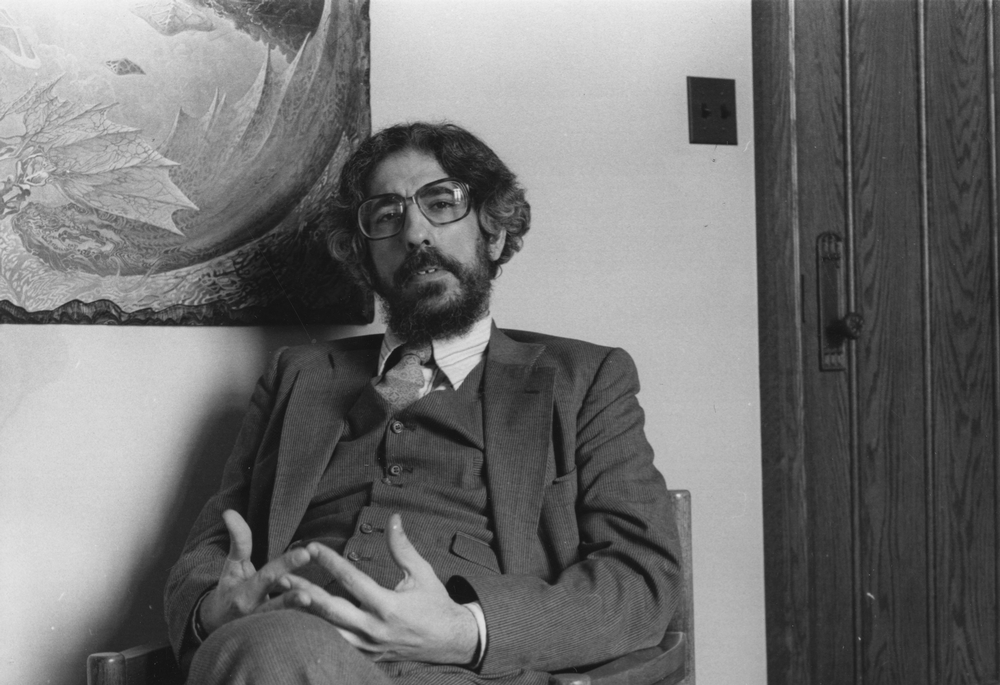

“He was trying to write about the Holocaust, and I just think he had no real ideas,” said Classics professor James Redfield (Ph.D. ’61), who taught at the University of Chicago for 50 years, retiring in 2016. He’s telling a story from the ’70s.

Redfield was the master of the New Collegiate Division, which runs Tutorial Studies (the College’s design-your-own-curriculum program), and he was fed up with having to accommodate this student.

But he knew just the man for the job: Jonathan Z. Smith, a historian of religion at the University of Chicago who is remembered by colleagues and students as an honest intellectual and an unshy critic.

Redfield will never forget how Smith, who was born Jewish but secular, responded to the paper.

“This is the first time I have ever felt sympathetic to anti-Semitism,” he said.

That was Smith’s style as a scholar. He was a brutal critic who pushed academia to join him in raw, deliberate analysis.

“He did not suffer fools gladly, either on the page or in person. He was critical in every sense of the word,” said Wendy Doniger, the Mircea Eliade Distinguished Service Professor of the History of Religions at the Divinity School, and a longtime colleague. “His critique of the way religion was studied is that it was not critical enough. Paradigms were not closely enough examined. He had a sharp mind, and he rightly wanted scholars to be more cold-blooded, more analytical in their treatment of religious phenomenon.”

Scholars throughout Europe and America listened to Smith and changed the way they studied religion, Doniger said.

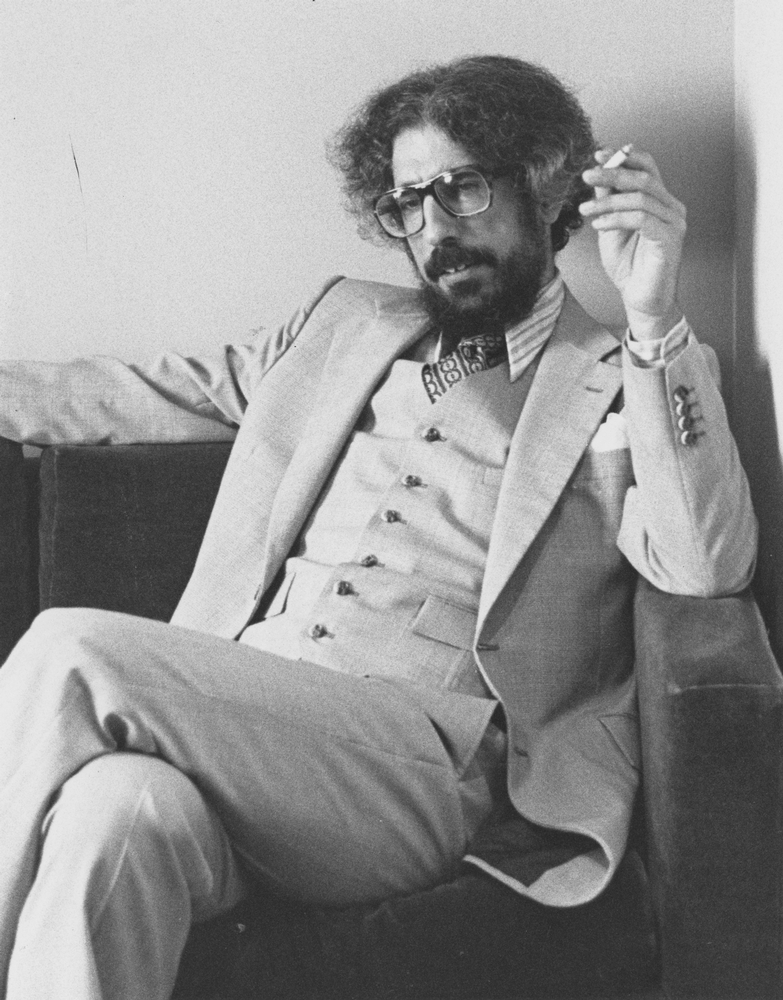

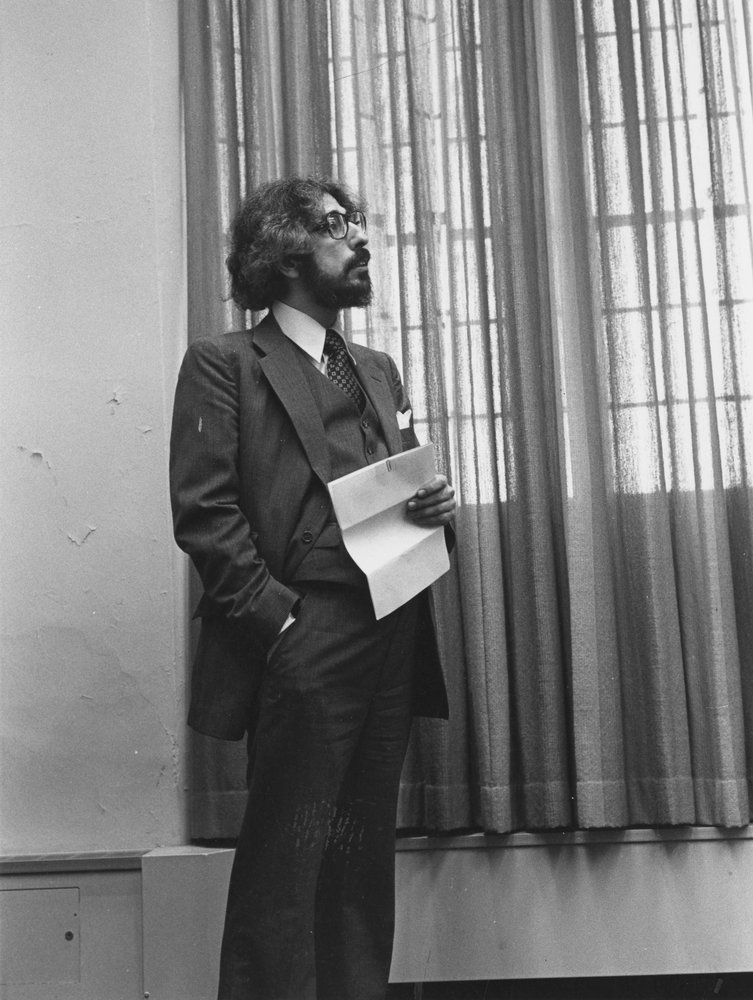

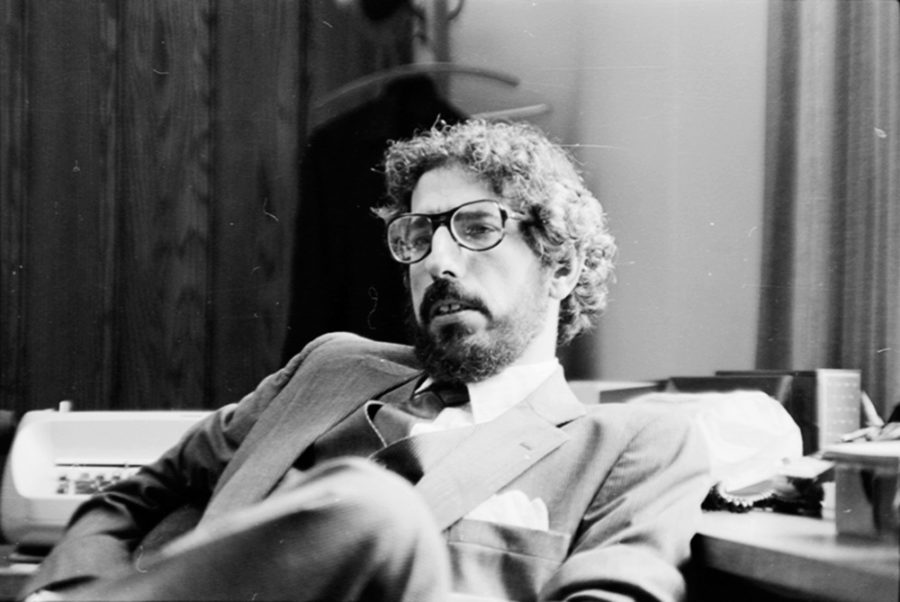

On campus, Smith was a beloved teacher. He taught prolifically at the University from 1968 until he retired in 2013, serving as dean of the College from 1977 to 1982. He was a sharp writer, a mesmerizing lecturer, and an intriguing character.

A lifelong smoker, he died suffering from lung cancer at age 79 on December 30.

Dean of the College John Boyer, who went to Smith for advice when he was offered the deanship in the early ’90s, said Smith was a wonderful man, loved by students, and an excellent colleague. Boyer, an expert on the University’s history, said his conversation with Smith when he was offered the deanship inspired him to write his book, The University of Chicago: A History.

“He told me he thought it would be very important for whoever took the deanship to try to give more of a public voice to the University’s and the College’s history,” he said, adding that Smith was always an interesting person for him to debate. “The thing about Jonathan is that you never quite knew which side of an argument he was on because he was able to see not only what emerged as his own point of view, but to understand and to give legitimate representations of other people’s points of view. You never quite knew where he was coming from, or where he was going until the end of the argument.”

Hanna Gray, whose 15-year term as University president from 1978–1993 overlapped with Smith’s deanship, said he was a remarkable teacher and colleague. She remembers the hard conversations they had about whether the College could be expanded from 2,700 to 3,200 students without losing its character.

“The important things about him were an extraordinary commitment to teaching—a wonderful commitment to teaching; a person of the highest kinds of standards; a person who taught really quite selflessly, that is, he didn’t think about how many courses a person was obliged to give. He gave more courses than anyone I know because he really loved it,” she said. “He was an extraordinary colleague and an extraordinary presence at the University, and that was in a way the most important thing about Jonathan Smith.”

‘An extraordinary presence’

Even in elementary school it was clear Smith was a bit different.

“There was something sort of extra-worldly about him as a youngster,” his childhood friend, attorney David Simpson, said. “He was interested in things that were beyond the usual purview of children—he marched to his own drum a little bit.”

They went to Hunter College Elementary, an experimental school for gifted students on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Simpson lived just a few blocks away from Smith’s home at 86th Street and Riverside Drive, and Simpson went over there quite often. He remembers that Smith was obsessed with animals and with learning about different cultures, Native American culture in particular.

Smith’s parents were a fairly ordinary Jewish couple: “They weren’t anything like what Johnny became,” he said.

They lost touch around age 12 when Smith went to Horace Mann School and Simpson stayed in public school.

As a junior Smith worked on a farm for an agriculture program that Cornell offered to high schoolers.

“I started off originally in grass breeding. That was what I wanted to do with my life,” he once said in a Maroon interview. “I went to a farm, because since if you’re a city boy going [to] an agricultural school which is free, you have to prove that you can stand in cow shit, so they send you to a barn for a while…. It still remains to this day the best thing I ever did in my life. But it was a bad time in Cornell’s history. They would let you take no liberal arts courses.”

Smith was frustrated that they wouldn’t let him study history or philosophy, so he protested to his headmaster who said, “That’s good, you’ll go to Haverford; they’ll figure you out there.” He made a phone call and got Smith into college.

On his first day at Haverford Smith scoped out the one spot in the library where it looked like you could smoke.

“Turns out it was a shrine where Quaker philosophers would study. And if there was one place where no one had ever smoked before, that was it. So there I was, happy as could be…. Then [philosophy professor Martin Foss] came in. Then some other students came in, and there was supposed to be a senior philosophy seminar on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind,” he said in the interview. “I was absolutely enthralled by [Foss’s] way of talking. So that afternoon I became a philosophy major.”

From there Smith went to Yale to study religion, finishing a 574-page dissertation on James George Frazer in 1969.

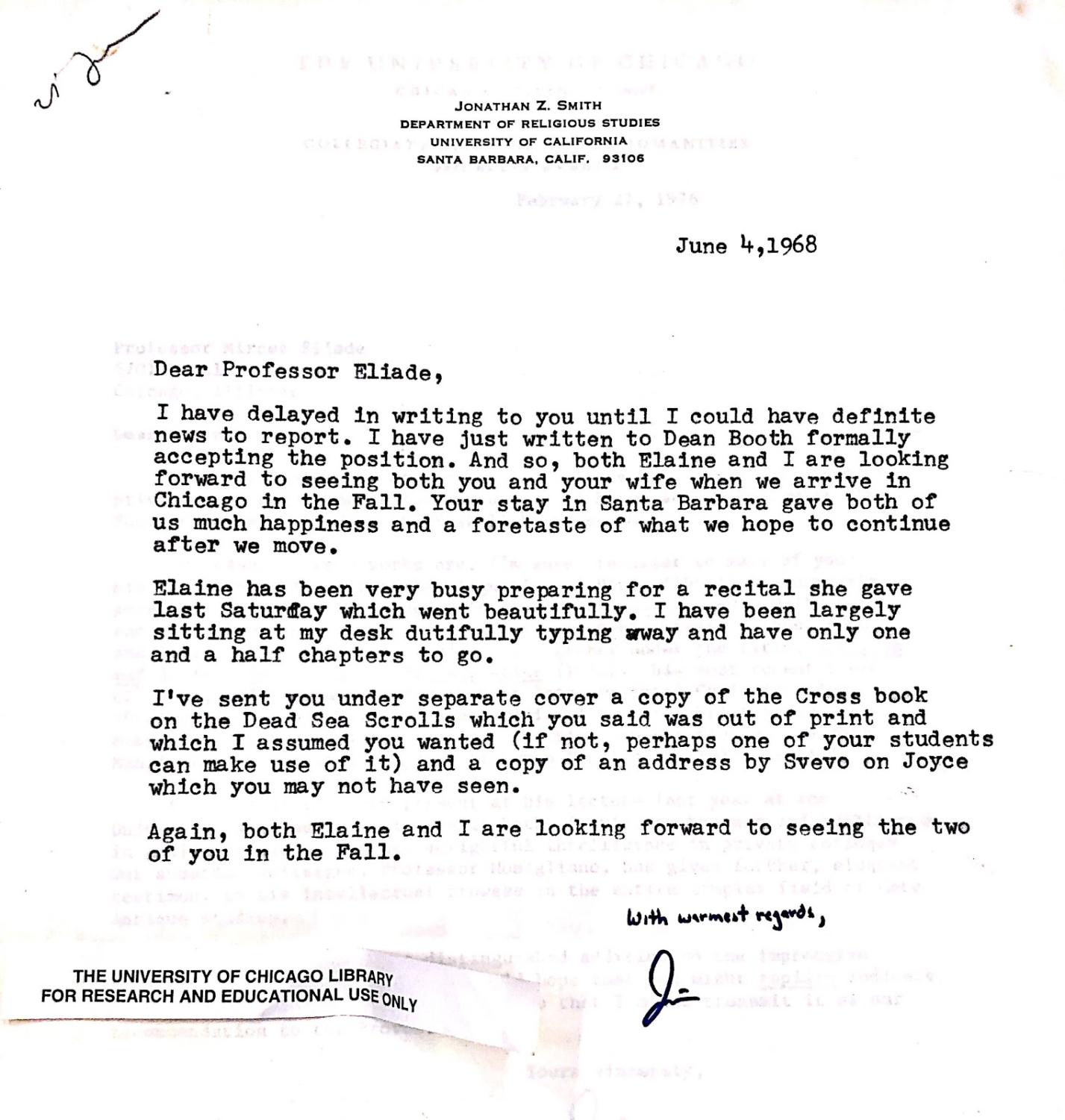

But the story of Smith and the University of Chicago begins before that, around 1968 with Hans Penner (Ph.D. ’65), a leading scholar in comparative religion at Dartmouth.

Penner died in 2012, but Charles Long (P.h.D. ‘62), a professor emeritus of religious studies at UC Santa Barbara, remembers the story. At the time, Smith was a young and promising scholar on the faculty in the just-established religious studies department at Santa Barbara.

Penner had gotten to know him at Dartmouth when Smith was an instructor there for a year from 1965–66, and he thought he would be a good fit at the University of Chicago. Penner excitedly told Long: “I met this person who thought like we thought at Chicago.”

Long was co-teaching a class called World History of Religions, one of the first courses in UChicago’s nascent New Collegiate Division, which was conceived as an interdisciplinary fifth division on top of the physical sciences, the biological sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities. “It was clear that it had legs,” Long said, remembering that the classes would overflow into the Swift Hall common room. He knew that the founding master of the division, professor Redfield, was still recruiting, and Smith seemed to him like a perfect candidate.

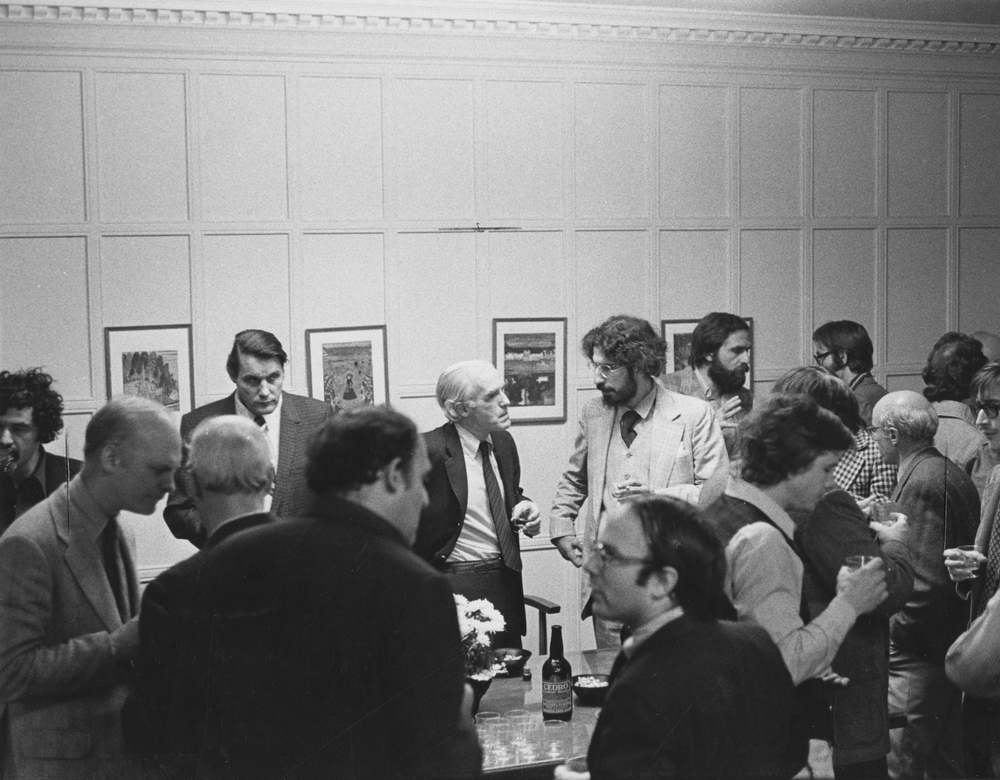

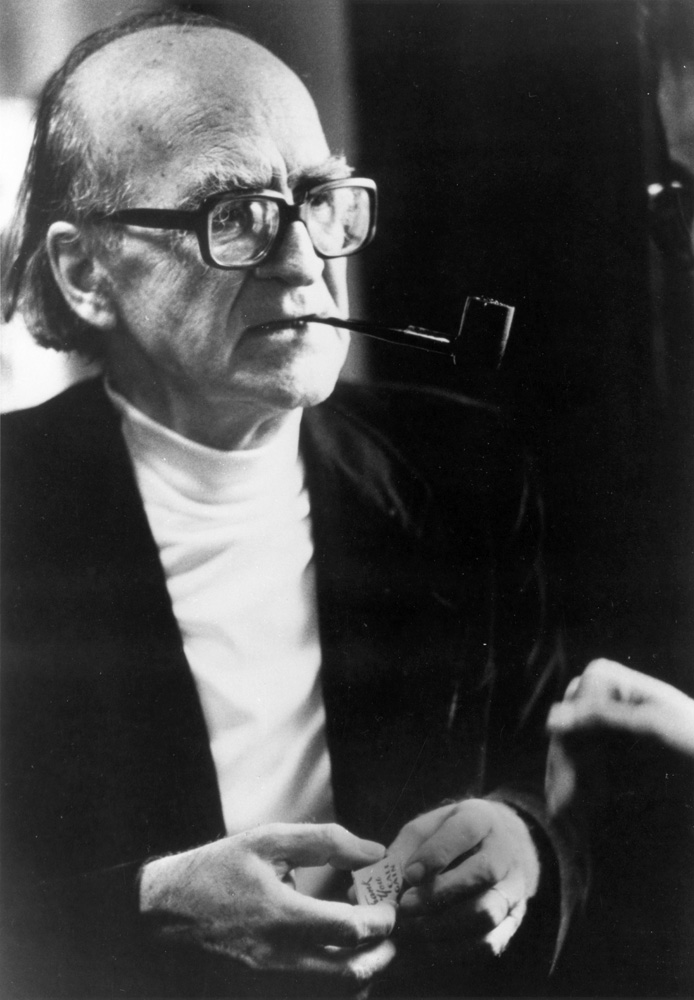

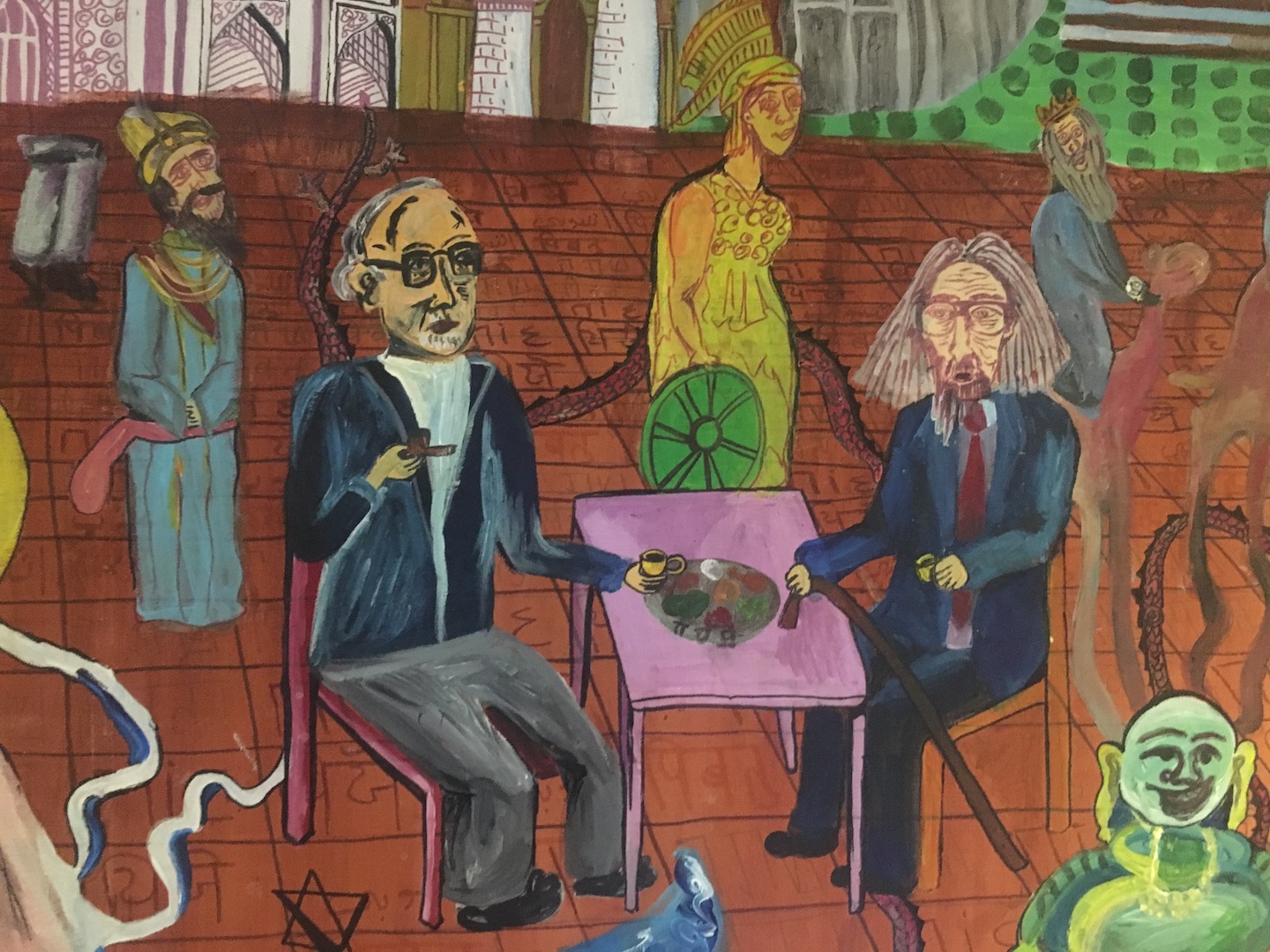

Upon Long’s recommendation, Redfield visited Smith in California, and he was immediately impressed. Mircea Eliade, then the most prominent professor at UChicago’s Divinity School, also met Smith out in Santa Barbara, on the evening of February 14, 1968, which was the day after Smith’s interview in Chicago and the day when Eliade arrived at UC Santa Barbara for a visiting professorship.

That summer, in a June 4, 1968 letter, Smith reported to Eliade that he had accepted the New Collegiate Division position and would be moving to Chicago.

“Dear Professor Eliade, I have delayed in writing to you until I could have definite news to report. I have just written to Dean [Wayne] Booth accepting the position,” Smith wrote. “Both Elaine and I are looking forward to seeing both you and your wife when we arrive in Chicago in the Fall. Your stay in Santa Barbara gave both of us much happiness and a foretaste of what we hope to continue after we move.”

On July 1, 1971, Eliade wrote to Dean of the Divinity School Joseph Kitagawa, recommending Smith be promoted to the rank of Associate Professor.

“I firmly believe that Jonathan Smith will become one of the most important historians of religions in the United States,” he predicted. “Of course, we must help him to realize his vocation, and I think that his promotion to Associate Professor is not only imperative, but overdue.”

At Chicago Smith lived up to Eliade’s high expectations: colleagues said they place Smith among a group of renowned University of Chicago scholars that includes Charles Wegener, Wayne Booth, and Jock Weintraub.

“I always think of Jonathan as being part of that old-school Chicago, which is extremely erudite, an intellectual polymath,” said history and law professor Dennis Hutchinson (J.D. ’70). “Not afraid to challenge any conventional wisdom, and also stylized: They never called each other ‘professor.’ It was always ‘Mr.’ and no honorifics, as there should be no hierarchy of learning or intelligence.”

College students were not to be called “undergraduates,” for Smith believed that would imply they were beginners, waiting to become real students when they went to graduate school.

“Smith thought this was all wrong and that college education was where it was at,” said Christopher Lehrich (Ph.D. ’00), a professor of religion at Boston University and a former mentee of Smith’s.

Lehrich later edited a collection of Smith’s writings about teaching, titled On Teaching Religion.

Smith came to be known as one of the most influential historians of religion of his generation, but Lehrich was inspired to put together the book when he discovered that there was a whole other side to Smith’s scholarly output: essays about teaching that were often “very radical.”

Lehrich remembers sitting in Smith’s office, talking to him about changes to the College and the Core. University president Hugo Sonnenschein was trying to expand the College—this time from 3,500 to 4,500 students. Too few students were applying to Chicago to allow for such an expansion, so the College had to move toward, as Sonnenschein said, “a curriculum more appealing to 17-year-olds.” The “Chicago plan” reduced the size of the Core from 21 to 15 classes.

Smith rejected this curricular trend away from a rigid core and toward “electivity,” which he took to mean the offering of more preprofessional tracks.

“I think that College students should be able to major in Undecided. It would be a wonderful thing if you didn’t have to major,” Smith proclaimed to Lehrich between drags on his cigarette.

“From Jonathan’s point of view, he loved the place, and he loved the students, and he loved what in his mind Chicago was devoted to and all about,” Lehrich said. “And so he was sickened to see what was happening to it. He could be a little bit sort of ‘the sky is falling!’ about everything, but I think he was horrified by things like the Chicago plan.”

Lehrich said Smith was so “greatly beloved by the students in part because he just didn’t seem to have any respect for anything, except, he loved the students and he loved the College.”

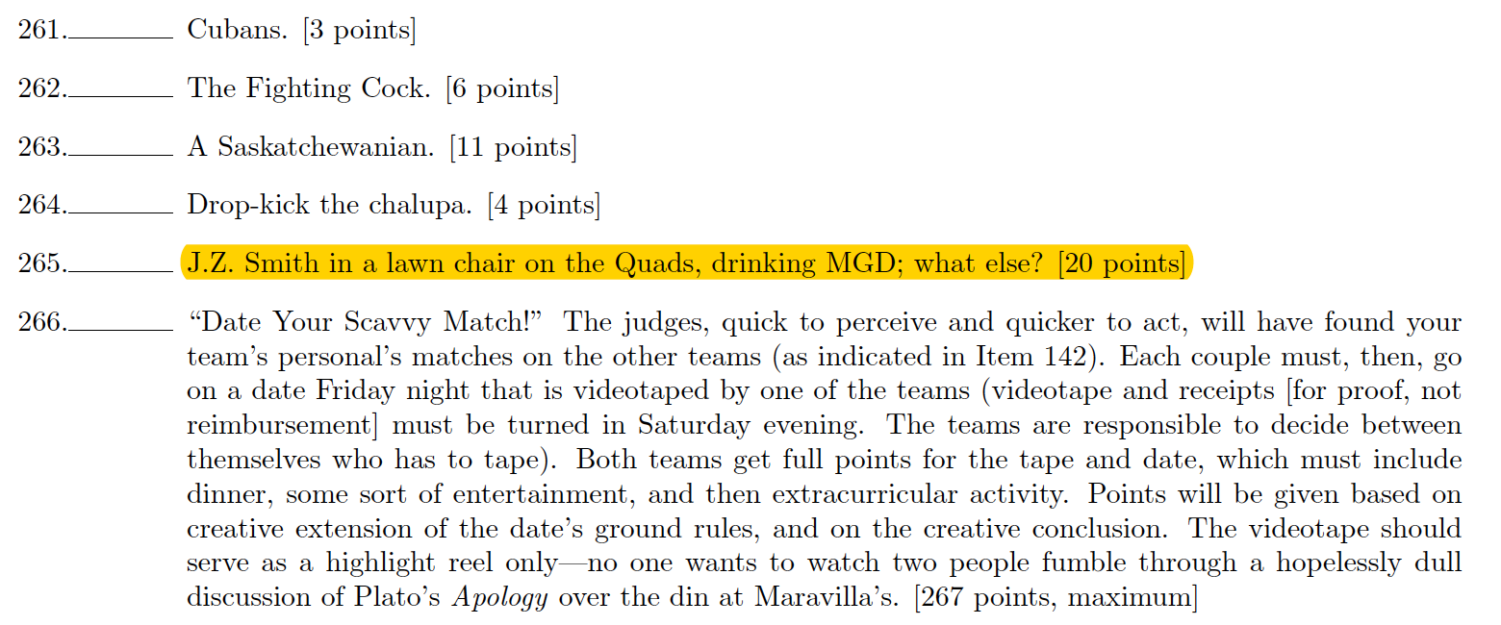

In 2000, item #265 on the University of Chicago Scav list was “J.Z. Smith in a lawn chair on the quads, drinking MGD; what else? [20 points].”

Smith was approached by one of the Scav teams, eager to collect points.

“Oh yes. Absolutely,” he told them, as Lehrich remembers.

And he lounged in a lawn chair and threw back a beer in front of the administration building.

“He was not pandering to the students. It’s like: The students want him to do something, and he can see why it’s funny. ‘Sure, I’ll be happy to do that.’ I don’t think he had any sense that this was beneath his dignity, or an inappropriate thing to do. No, it’s part of the College life,” Lehrich said.

Smith was a private person; he organized his life to maximize time for reading and thinking. At the same time, however, he was a very human presence on campus.

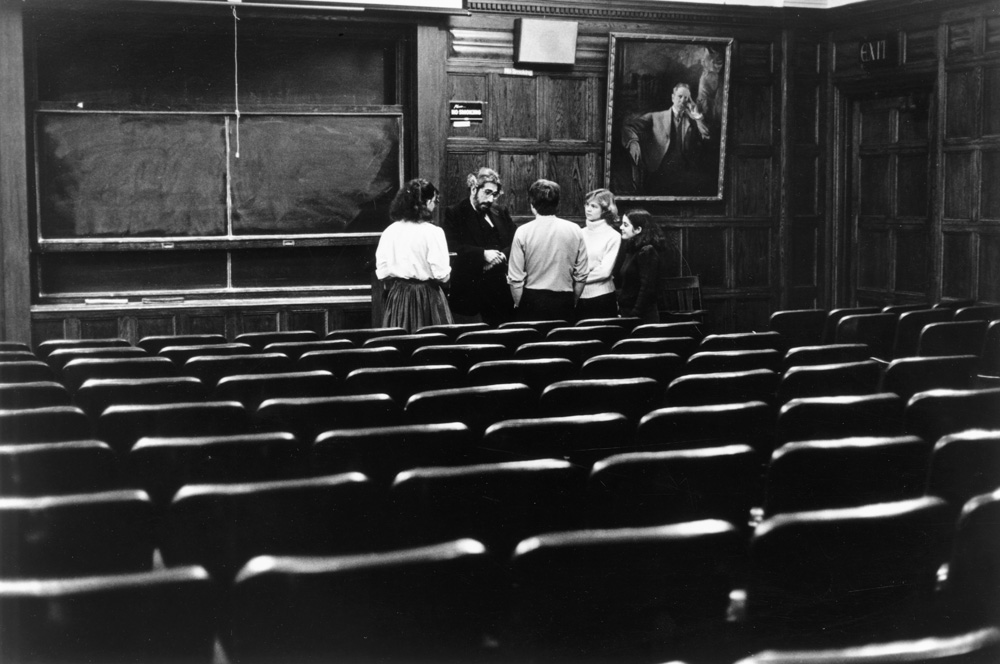

He ate lunch in Cobb Hall before class and had coffee in Swift Hall after class, and he welcomed his students to join him.

Doniger remembered that Smith always commanded the attention of a room when he talked.

“He smoked; he was a chainsmoker. And he would let the ash on his cigarette roll longer, and longer, and longer, and longer. And everyone in the room was mesmerized watching the ash on the end of his cigarette, waiting for it to fall. You could’ve heard a pin drop,” she said.

If his character and presence brought people in, it was his ideas that kept them engaged.

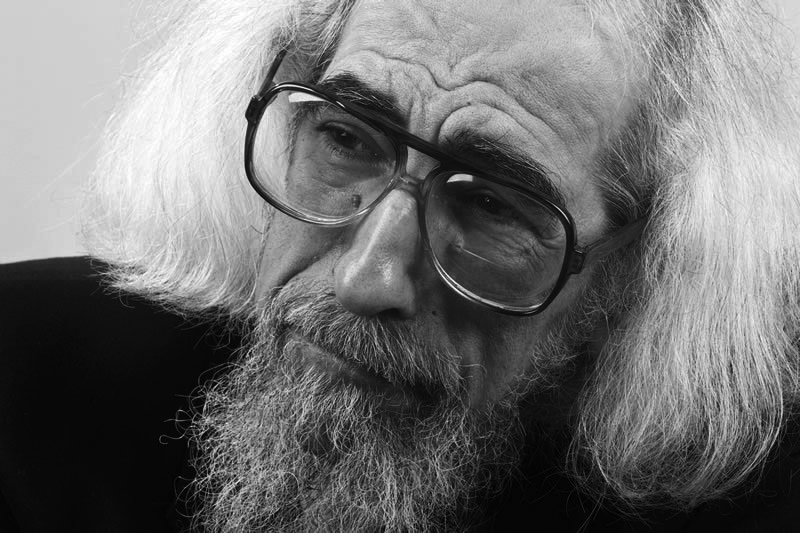

“That crazy stick he walked with in recent years and so forth—that kind of made him a beloved character around campus. But the reason you listened to him when he talked was because he was a brilliant and arresting speaker,” Doniger said. “He was just smarter than anybody else.”

As Smith aged, he grew out his beard, carried a hand-carved cane, and wore huge glasses.

“I’m going to invent myself as this old guy!” Long remembers Smith saying to him, around the time he started losing his curly black hair.

“The giant rhododendron cane, the beard down to his navel— He was a character, and he knew it. And he took advantage of it,” Hutchinson said. “It made him more engaging: What’s this guy on about? What’s his intellectual agenda? And it turned out his intellectual agenda would get people to think. And I think one of his accomplishments of being in the College—and something John Boyer has carried on—is he viewed himself as a spokesman for liberal education: What are we trying to do here? How do we do it? Is the Core such a good idea, or is the Core authoritarian?”

The College was his home

Unusual for a scholar of his stature, Smith almost exclusively taught College students.

“He did not teach doctoral students,” said Harvard Divinity School professor Kimberley Patton. “I mean, that is unheard of. He could have taught them, and he could have easily been chair of the department for years and years and established a doctoral dynasty.”

Colleagues and academics have different theories for why this was. It’s clear that Smith wasn’t interested in teaching students who were highly specialized or pursuing a preprofessional track. He did not like that graduate students already had their minds made up; to Smith, college students tend to be more intellectually honest because they are more open to being influenced. That was the theory, at least.

“I think his view was that doctoral students were so far socialized into repeating what they thought their professors wanted to hear that you often didn’t hear what they really thought,” Patton said.

Lehrich, one of only a handful of Divinity students whose dissertations were supervised by Smith, said he probably felt graduate students were in it for the wrong reasons: Most of them “wanted to say, ‘Oh, I worked with J.Z., so I’m a strong candidate.’ He wasn’t interested in that kind of thing.”

But this is probably not the full story of why Smith distanced himself from the Divinity School.

Smith held very strong and particular views about teaching that made it challenging to find the right place for him at the University. A year or two into Smith’s three-year appointment in the College, he came to Redfield’s office and explained that he wanted to go to the Divinity School full time.

“I can’t believe I can’t make something that works for everybody,” Redfield remembers telling Smith, referring to the New Collegiate Division he founded.

“You may remember that the Creator had the same problem,” Smith quipped back.

Smith didn’t last long at the Divinity School. By 1973 he had designed his own undergraduate program in the College—Religion and the Humanities. He officially resigned his Divinity School affiliation in 1977.

“The religious studies program coming out of the Divinity School was seen as a direct counterpoint to Jonathan’s own religion program, so there’s some intellectual tension involved in how he developed and applied his field within the University,” said professor Hutchinson, now the master of the New Collegiate Division. “He saw religion, as far as I understand his views, as more of a conversation—an act of creation—whereas so many in the Divinity School, at least when he was kind of railing against them, were much more academic in the sense of specialized key areas and more of the graduate taxonomy of specific knowledge—he saw no use for that.”

Professor and former Divinity School Dean Margaret Mitchell explained that Smith is perhaps most famous for his argument that scholars produce religion: “Religion is solely the creation of the scholar’s study,” he wrote in a 1982 book of essays, Imagining Religion. “It is created for the scholar’s analytic purposes by his imaginative acts of comparison and generalization. Religion has no independent existence apart from the academy.”

She notes that the co-director of Religion and the Humanities was Divinity School professor Anne Carr, but she still said that “to some degree Smith thought of the major as an alternative to the Divinity School.”

Mitchell said that Smith had a remarkable ability to talk across ideological divides. She said he is “the figure who has most left his mark on the American Academy of Religion, and yet he was also the president of the Society of Biblical Literature.” (The two groups had a divorce about a decade ago.) She said there’s no other scholar who could speak across the field of the study of religion like Smith.

“He is the person who almost everybody in the study of religion has read, and thought with, and interacted with. His mode of exposition was the essay. Most of his oeuvre—his scholarly work—is really brilliant collections of essays. And what he’s known for is both theorizing about the nature of comparing religions, and setting up himself really interesting pairings of artifacts and texts from very different contexts, and bringing them into conversation,” she said.

His mode of teaching was the lecture. He typically wrote out his lectures by hand before each class. It took him at least three or four hours of preparation to give one hour of lecture, and until near the end of his career he would throw out his notes on the last day of the quarter to force himself to design his next course from scratch. Mitchell, who sat in on some of Smith’s classes, described how his lectures set up comparisons of unlike things that always seemed out-there at first, but Smith would bring them together in a way that was masterful and compelling.

Ideological differences

While Smith seems to have had real disagreements with the Divinity School at times, nearly everyone who spoke to The Maroon for this story pointed out that he had a remarkable ability to separate intellectual disputes from personal relationships.

Smith used Friedrich Nietzsche’s note to readers in Ecce Homo, “I am one thing, my writings are another,” as an epigraph to his 2010 address at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion in Atlanta, Georgia.

Smith was invoking the Nietzsche line in a different context—he was modestly resisting the concept that there is that much to learn from a scholar lecturing about his own life—but the choice of that epigraph speaks to his belief that there was an important distinction between scholars and ideas. He was in the business of taking down the latter.

Patton and Doniger both remembered that Smith played a significant role in organizing the University’s 100th anniversary conference for Eliade in 2007, despite Smith’s frequent criticism of Eliade.

Patton co-edited a book that collected responses to Smith’s 1982 essay In Comparison a Magic Dwells. Smith argued in that influential essay that comparison in the human sciences was practiced in a way that was problematically unscientific, with a lack of objective and agreed-upon rules (ie. “magic”). It was a devastating critique of comparative religion, and it had a profound impact on the field. Mitchell credits Smith for the establishment of models and criteria for responsible comparison.

The essay was not a critique of him specifically, but Patton said that Eliade, who was in the field of comparative religion, “typified for Smith much of what was problematic about the field.”

At the University’s commemorative conference, Eliade’s work faced significant criticism, and Smith certainly could have piled on.

But he didn’t, and instead chose to present a defense of Eliade. He wrote a “wonderful article” defending Eliade as a scholar of religion, Doniger said, which was presented as a lecture at the conference and then published as an article in the book that came out of the conference.

“Most people would not do that for someone whom they had critiqued so powerfully, with whom they had disagreed so much. And yet he did. Why? Well, he liked Eliade, and he felt he was just a really important—and he was—scholar in the field of the history of religions,” Patton said.

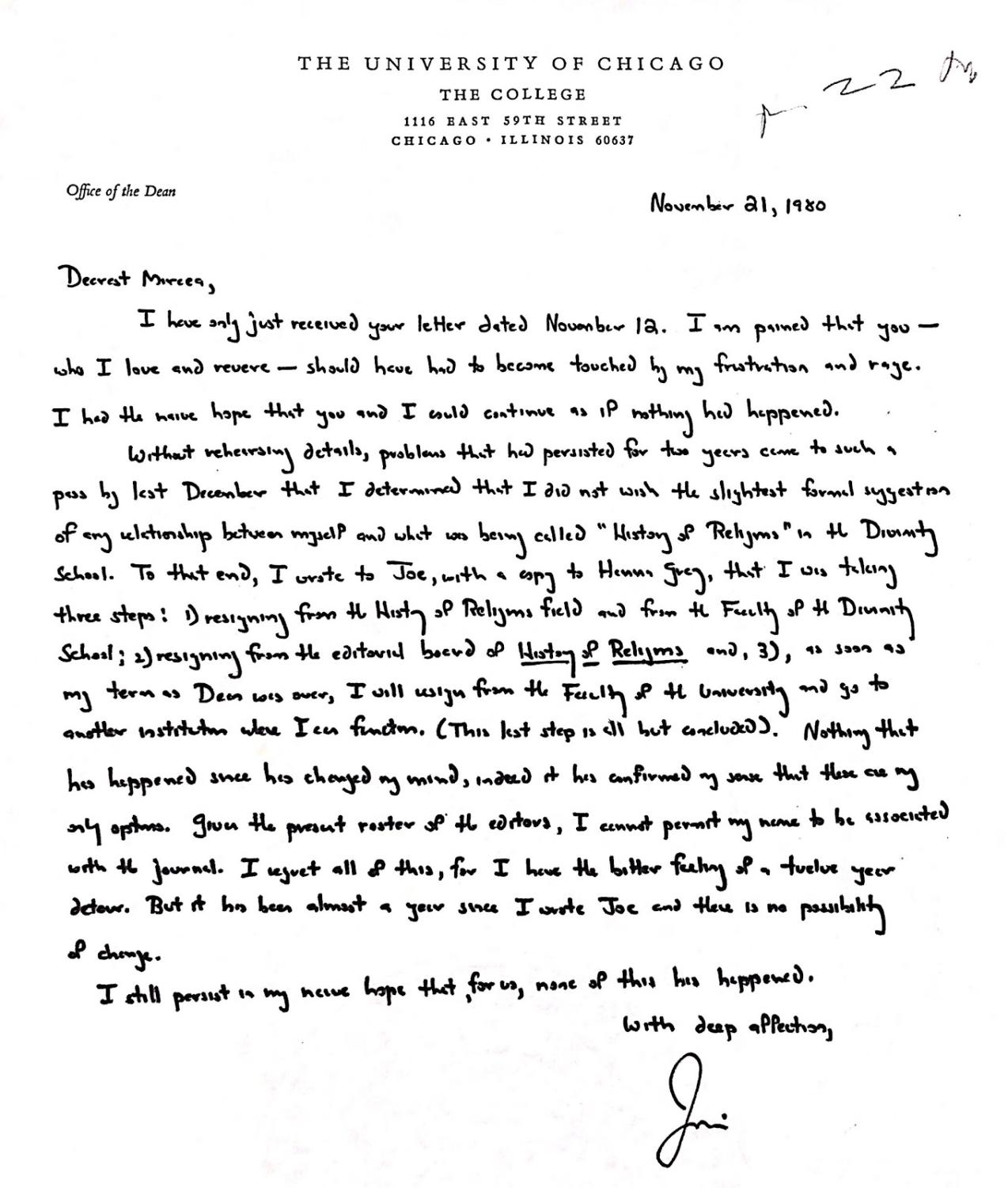

It’s clear in Eliade’s archived papers and correspondences that he and Smith were good friends, but the last letter from Smith in Eliade’s collection, dated November 21, 1980, takes a sad turn. Smith writes that he is pained that Eliade was touched by his rage, explaining he wanted to have no formal relationship with the Divinity School. To that end, he planned to resign and leave for a different University in 1982, when his five-year term as Dean of the College would end.

“I had the naive hope that you and I could continue as if nothing had happened. Without rehearsing details, problems that persisted for two years came to such a pass by last December that I determined that I did not wish the slightest formal suggestion of any relationship between myself and what was being called ‘History of Religions’ in the Divinity School,” Smith wrote. “I still persist in my naive hope that, for us, none of this has happened.”

Smith did not leave the University, but The Maroon was not able to put together a complete account of what changed his mind. “I didn’t know about the letter, but he did consider leaving the University and they wooed him back and he stayed,” Doniger said.

Smith’s legacy as dean of the College

Professor Hutchinson met Smith in 1981, the first month he joined the faculty, when there was a holdup with his appointment.

“That’s a bureaucratic snafu! I can take care of that. What a stupid rule!” Smith told him animatedly.

“He had just no pretense, no decanal affect. And I immediately warmed to him,” Hutchinson said.

Smith could navigate University bureaucracy and get things done.

Katherine Karvunis, who was Smith’s assistant for the nine years he was an administrator (1973–1982), spoke in awe about his productivity. He dutifully followed through on all tasks, he made every meeting, and he was very easy to work with, she said.

President Gray was disliked by a lot of students because she was seen as too focused on fundraising. Smith, however, wasn’t thought of as a money-grabber; he was regarded as someone who cared about academic standards, multiple alums from that era told The Maroon, remembering that Smith was dean at a time when the University was more apathetic toward College students.

“He was very well-liked by a student body that didn’t like many administrators,” said Abbe Fletman (A.B. ’80), a judge in Philadelphia, who was editor-in-chief of The Maroon from 1978–1979.

But not everyone remembers Smith as the outlier in a cold administration. Wendy Oliver (A.B. ’81), now a business attorney in Portland, Oregon, described the administration during this time period as “indifferent at best to students. It was kind of like an English boarding school, where they felt they needed to toughen you up,” she said, adding that Smith was at least partially responsible.

Oliver recalls being brushed off by Smith after going to his office to request a sexual misconduct investigation. According to Oliver, a professor had told her to come to his apartment to pick up an assignment, offered her a drink, and then tried to proposition her sexually in exchange for a grade, asking: “What’s it going to be: an A or a B?”

A January 22, 1982 Maroon story about the administration’s mishandling of her complaint explained that Smith had told her he would investigate the allegations fully. During their meeting, however, Smith treated her report lightly: “He went on to tell me little anecdotes about other cases of female harassment where professors met their students at the door in a bathrobe or something…. He thought it was funny,” Oliver was quoted saying.

“It was certainly another time. The College was just not very responsive to students. It was just not a very friendly place to be. And I don't think anyone I knew considered the administration to be friendly or helpful,” she said.

When Smith informed then-Divinity School Dean Joseph Kitagawa of his intent to leave the University at the end of his term as Dean, he would have been in the process of overseeing a major review of the University’s curriculum.

Even during that process he indicated he didn’t want to continue as Dean for another term. In the May 4, 1979 issue of the Maroon, Smith was interviewed about his three-year curriculum review.

“I want it done before I go out,” he said, also describing the review as “huge, the most significant report in the history of the College.”

Karvunis said Smith wanted to do a complete reevaluation of the Core, but he was somewhat constrained by Gray, who Karvunis said didn’t want to make sweeping changes to the degree Smith wanted.

Gray, however, insists she agreed with Smith completely.

“We both agreed entirely on the opposition to pre-professional education, and believed that it was in the tradition of the College and a distinctive strength of the College that half of its program was devoted to that kind of broad education…. And we believed in the importance of the commonness, that is of students all sharing at least some important portion of their education so they could really learn from each other as well,” she said.

Smith articulated his views on the Core in an epic two-hour 2008 interview with Supriya Sinhababu (A.B. ’10) for the inaugural issue of The Maroon’s revived long-form publication Grey City. Sinhababu reflected on that conversation a decade later for this story.

“He’s this guy with the giant glasses and the beard and a walking stick. I mean, he looks like a wizard. He died at 79, but in my head he’s at least like a thousand. He really feels like a legendary figure.”

Smith never used a computer and despised the telephone, so it wasn’t always easy to contact him. His aversion to technology stemmed from his desire to maintain uninterrupted time when he could focus on thinking and writing, said chair of the religious studies department at Yale, Kathryn Lofton (A.B. ‘00), who majored in Smith’s Religion and the Humanities program.

Lofton regularly went to Smith’s office hours, and she said she would always have headphones in her ears.

“He would ask me whether I could hear anything over the noise of my music. And I would say, ‘I want the noise,’ and he would say, ‘I don't know if you can hear anything that way.’ We probably had exchanges along these lines ten different times,” she wrote in an e-mail. “I never gave up the Walkman, and he never gave up his sense that listening to a Walkman while walking defeated the point of music and walking. Yes, it was a Walkman. This was 1996-2000!”

All Sinhababu had to get her interview was Smith’s address, so she went and knocked on the door of the Greystone house where he lived, just up the street from Salonica, the corner diner where he was a regular.

“Which I felt like a creep about, but in the absence of any other choice I decided to knock on his door. And when I did so, his wife answered kind of through the glass screen door. And by answering, I mean she looked through the glass at me. And kind of stared at me for a couple seconds and left. Like, ‘Who is this person? I don’t know you.’ But his door had a mailslot, and so I dug a little piece of paper out of my backpack, wrote the interview request on it, and slid it through. Apparently he got it.”

She said her interview with Smith was—by far—the most-read article she ever wrote. “Obviously that was due entirely to my subject,” she said. “We tried to put the whole thing on the website but it actually broke the character limit for an article at the time. I kept getting e-mails for years afterwards, like, ‘This is a great interview, but why does it cut off at the end?’ It speaks to just how interesting he is and how much people want to know about him. Even after reading thousands and thousands of words they want more.”

There’s one more memorable story about Smith and the Maroon.

The front page of the paper on May 4, 1979 had two photo slots, each one column in width: One was Jonathan Z. Smith; one was a police sketch of a rapist in Hyde Park.

Smith’s picture should have appeared under a headline about the College’s ongoing review of the Core, but you can guess the mistake when the printer went to line up the photo negatives with the corresponding picture slots.

Fletman, the editor at the time, said she called the Dean immediately so he would not have found out about it another way.

Chris Isidore, a senior business writer at CNN, who was editor-in-chief of The Maroon in 1982, remembers that Smith was easy-going, answering the phone as ‘the friendly neighborhood rapist.’

“I of course had great trepidation about making this phone call, but he was very good humored about it,” Fletman said. “It’s a good story because it does really reflect what an accepting guy he was.”

The joke at The Maroon was that the rapist was furious because he didn’t want to look like Smith.

The papers were picked up from newstands, and the corrected version made it to the library’s microforms collection.

‘An after-dinner speaker’

Smith’s status in the administration and his membership on two national commissions that issued major reports on liberal education drew “attention to the continued musings of a college teacher,” he said in his self-written preface to Lehrich’s collection of his essays.

Smith came to be regarded as somewhat of a thought leader in higher education, giving 150 addresses at universities, professional associations, and conferences over the years. He started calling himself “an after-dinner speaker,” Lehrich said.

While advancing his beliefs about education Smith tried to hold the University to its own word, and he was an excellent spokesperson for principles he saw as fundamental to the University.

His talks would get published, but often in remote, out-of-the-way journals.

“Some of these essays really challenged the whole notion of how collegiate education ought to be done,” Lehrich said. “I felt that this stuff shouldn’t be forgotten.”

He worked with Smith to find copies of his lectures and to select which ones to include. “It’s the kind of thing a graduate student does for an old mentor.”

Central to Smith’s education philosophy was what colleagues came to refer to as “Smith’s iron law”:

A student may not be asked to integrate what the faculty will not.

This law manifests itself in Smith’s first three rules for teaching (as printed in Lehrich’s collection, On Teaching Religion):

- Students should gain some sense of mastery. Among other things, this means read less rather than more. In principle, the students should have time to read each assignment twice.

- Always begin with the question of definition, and return to it.

- Make arguments explicit. Both those found in the readings and those made in class.

An application of this law is found in the ‘08 interview. Sinhababu asks about his criticisms of the Core:

I think the Core, if it were a Core, is terrific. Now, the thing about a Core is it really has to represent a hard-won faculty consensus… It has to be that of all the books we could possibly inflict on you—only in 10 weeks, and you waste the first week, you waste the last week, so you’ve got eight weeks. If they're not crazy, they're going to take two weeks to read a book. So you're down to four books. Now what that Core really ought to be doing is saying that out of all the books in the world, these are the four books you should read. If they're not prepared to say that, they should shut up shop. That's my first comment… The second issue is I really think that if it’s a Core, there shouldn't be so many of them. How can you say “we hold these truths to be self-evident, and by the way we've got eight sets of truths. You can choose which one you’d like to take.” I’m not a fan of the fantasy of the Core in the days when on Wednesday, April 8, every student was reading exactly the same page of Plato. It’s the automaton theory of uniformity. I mean, stick with one or two, but then it’s five, six, seven, eight. The word fundamental means something or it doesn't mean something.

So what made something “fundamental” to Smith? What would a proper, “hard-won faculty consensus” look like?

In line with rule #2, Smith’s talks usually involved creating definitions, as did his writing. “His notion of the argument always had to do with a discussion about language…. He thought universities were special arenas for the clarifications of language and therefore the argument,” Long said. Mitchell calls him their field’s “great definer,” like a “modern-day Aristotle” because his work was obsessed with the question of classification and organization of material.

The 1982 Aims of Education address challenged Smith because it forced him to define two words.

Referencing a dictionary definition of “aim,” Smith said in his speech to first-years, “If, ‘aim implies a clear definition of something that one hopes to effect,’ then my assigned title puts me in double jeopardy. For it requires a ‘clear definition’ of education (no small task), a clarity, even if attainable, that seems to be placed at risk by the pluralism of ‘aims.’ If education, in the context in which we gather this evening, means baccalaureate education or liberal education, the problem is intensified,” he said. “What, then, to do? I was about to give up and hunt for another title, when my eye was caught by the etymology of ‘aim.’”

The word “aim,” he explained, is derived from the old French verb for “to guess,” giving Smith some solace because there is confusion and uncertainty built into it.

He declared that he was retitling his address, “A Guess About Education.”

“Regardless of the academic calendar employed, there is almost always less than one hundred hours of class-time in a year-long course. … We do not reflect often enough together on the delicious yet terrifying freedom undergraduate education offers by these rigid temporal constraints…. A college curriculum, whether represented by a particular course, a program, or a four-year course of study, thus becomes an occasion for deliberate, collegial institutionalized choice. This, then, is what our common discourse needs to be about.”

The talk continues, and Smith pauses to wrestle with defining the word “interesting.” He says that when we use the word interesting, we often use it to mean “tres amusant,” French for “very amusing.”

But the “very amusing” is not fundamental, and it shouldn’t be the basis of a curriculum.

“Translated into the world of collegiate education, such a gossipy, inconsequential understanding of ‘interesting’ is what often governs the elective curriculum, and, all too often, the survey course.”

What Smith wanted was “quality,” Redfield said. “He was always looking for it.”

Smith, in the Aims address, moves on to another understanding of the word “interesting”: the one that his iron law says ought to ground a college curriculum.

“In this understanding, things that are ‘interesting,’ things that become objects of interest, are things in which you have a stake, things which place you at risk, things which are important to you, things which made a difference,” he said. “Courses must be designed to be ‘interesting.’ For, students cannot be asked to be consequential while the faculty abstains. Students cannot be asked to integrate what the faculty will not. Students will not be critical if the faculty is not.”

Smith is survived by Elaine Smith, his wife, and two children: Siobhan Smith and Jason Smith. Reached by phone, Elaine said they had already given the University all the necessary info for its obituary, which was published a few hours later. She put Jason on the phone, who said they could consider responding to questions by email. Jason did not return email inquiries. Smith’s death notice said there would be no funeral or memorial service.

Verdery Doolittle Kassebaum / Nov 19, 2022 at 10:05 pm

At the University of California, Santa Barbara, in the mid-to-late 1960’s, I took a series of four of Jonathan Smith’s courses in the Religious Studies department: New Testament, Old Testament, Judaism, and Ancient Near Eastern Religions. His classes were always interesting and quite often humorous. I had started as a Psychology student, but learned much more about humans from his lectures, and soon switched to Religious Studies. I never regretted that decision.