Nothing happens in a vacuum, Otobong Nkanga reminds us in her first American museum survey, To Dig a Hole That Collapses Again, which is now on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Born in Nigeria and currently based in Antwerp, Belgium, Nkanga mobilizes a variety of media to reveal the many interdependencies created by global capitalism and colonialism. Much of her work calls attention to one particularly fragile relationship that we often overlook: the relationship between our bodies and the landscapes we inhabit.

This relationship is tied to the legacy of colonialism. When we think of colonialism in the 19th and 20th centuries, we consider extraction, production, and consumption: Paternalistic superpowers extract natural resources from their colonies, manufacture these resources into industrial products, and sell them to consumers around the world. Though this paradigm may be simplistic, this process often decimates the landscapes of colonial territories, leaving scars that are still visible today.

To Dig a Hole That Collapses Again takes its name from one such scar. Several years ago, Nkanga visited the town of Tsumeb, Namibia, on which German capitalists gutted rich mineral deposits using local labor in the early 20th century. Tsumeb is now speckled with amorphous striated pits leftover from the previous century of mining. The town’s name literally translates to, “To dig a hole that collapses again.” In his monograph on the exhibition, MCA curator Omar Kholeif writes that the name suggests “the continual eruption and corrosion of a landscape, or perhaps a body consistently attempting to reconstruct or protect a site of mystical beauty only for it to be destroyed.”

A performance by Nkanga to launch the exhibition portrayed this connection between landscapes and bodies even more clearly. Nkanga stood surrounded by her sculptural piece, “Solid Maneuvers,” a series of three-dimensional abstractions of Tsumeb’s pits. Moving jerkily as if to suggest a crane or some other industrial machine, the artist scooped up mineral particles contained in the sculpture, swung her arm around while particles escaped her closed fist, and deposited the remaining minerals elsewhere while counting or issuing commands like “Drop!” The performance suggested not only our alienation from our environment, but moreover the futility of the modern ideal that humans are—or ought to be—predictable efficient mechanisms. While performing, Nkanga narrated surreal tales about individuals caught in the sweep of industrialization who cannot be sustained by their new lifestyles, forcing us to question the sacrifice we make in exchanging industrialization for our relationship with nature.

The permanent works in the exhibition express similarly nuanced critiques. “The Weight of Scars” exemplifies Nkanga’s characteristic use of woven textiles, surreal forms, map-like motifs, and photography. Photographs of marred landscapes, which serve as indices of market-driven extraction, are caught in a white web pulled ever more tightly by maimed human forms. Their labor is depicted as responsible for their own disfigurement. The piece reiterates questions the artist poses in a video outside the gallery: Why don’t we treat our environment as we would our bodies? Why do we view them as separate entities?

Another impressive work is “Carved to Flow,” in which circular towers are composed of bricks of soap. The soaps are made of materials like oil, butter, charcoal, and lye, which are extracted from various regions before they are combined into a single consumer commodity and once more distributed all over the world. This circularity is echoed by the form of the soap towers. “Carved to Flow” is not heavy-handed in its critique of global capitalism; it simply reminds us that the very products we use to nourish our bodies, and whose trade forms the staple of our societies, often have a completely different impact on the bodies and societies from which they spring. Nkanga urges us to remember this impact, which is precisely why visitors have the opportunity to purchase the soap at select times while the exhibition runs. Proceeds go to Nkanga’s Carved to Flow Foundation, which supports education about the value of land, natural resources, and ancestral knowledge in Nkanga’s native Nigeria.

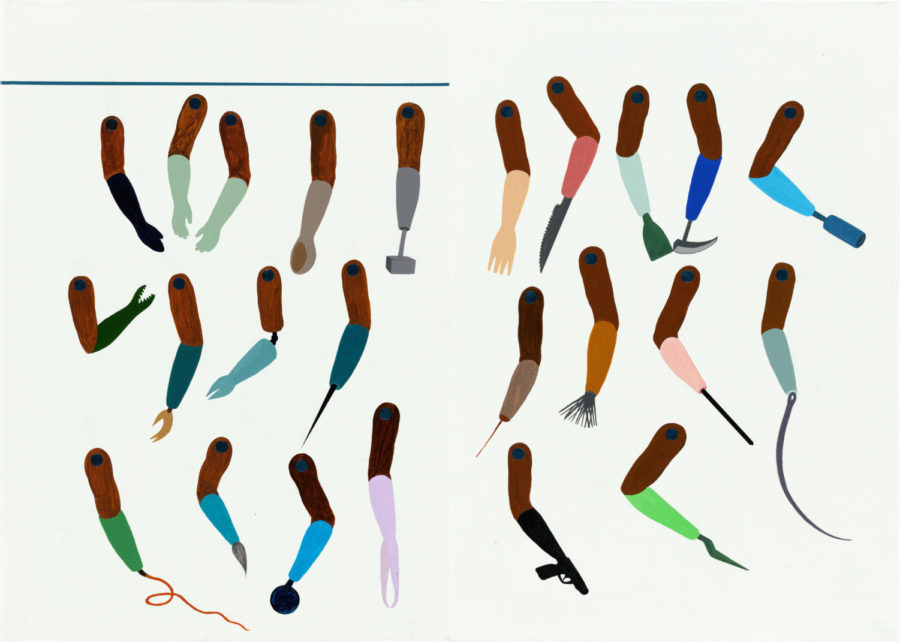

As Nkanga said to Kholeif at the exhibition’s opening, “the whole world is actually a colonial space.” To Dig a Hole That Collapses Again helps to bridge the gap between the individual and the legacies of colonialism, particularly as they relate to the environment. In a particularly captivating piece, a collection of abstracted arms each culminates in some sort of tool, be it a hammer, a gun, or a paintbrush. Though we may live in an industrial world full of modern demands, we still have the agency to choose how we interact with our surroundings, and what mark we make on our environment.

To Dig a Hole That Collapses Again continues at the Museum of Contemporary Art until September 2. “Carved to Flow” gallery performances will offer viewers the opportunity to purchase soap for the benefit of the artist’s Carved to Flow Foundation on Tuesdays and Fridays, noon–7 p.m., and on Saturdays and Sundays, noon–3 p.m.