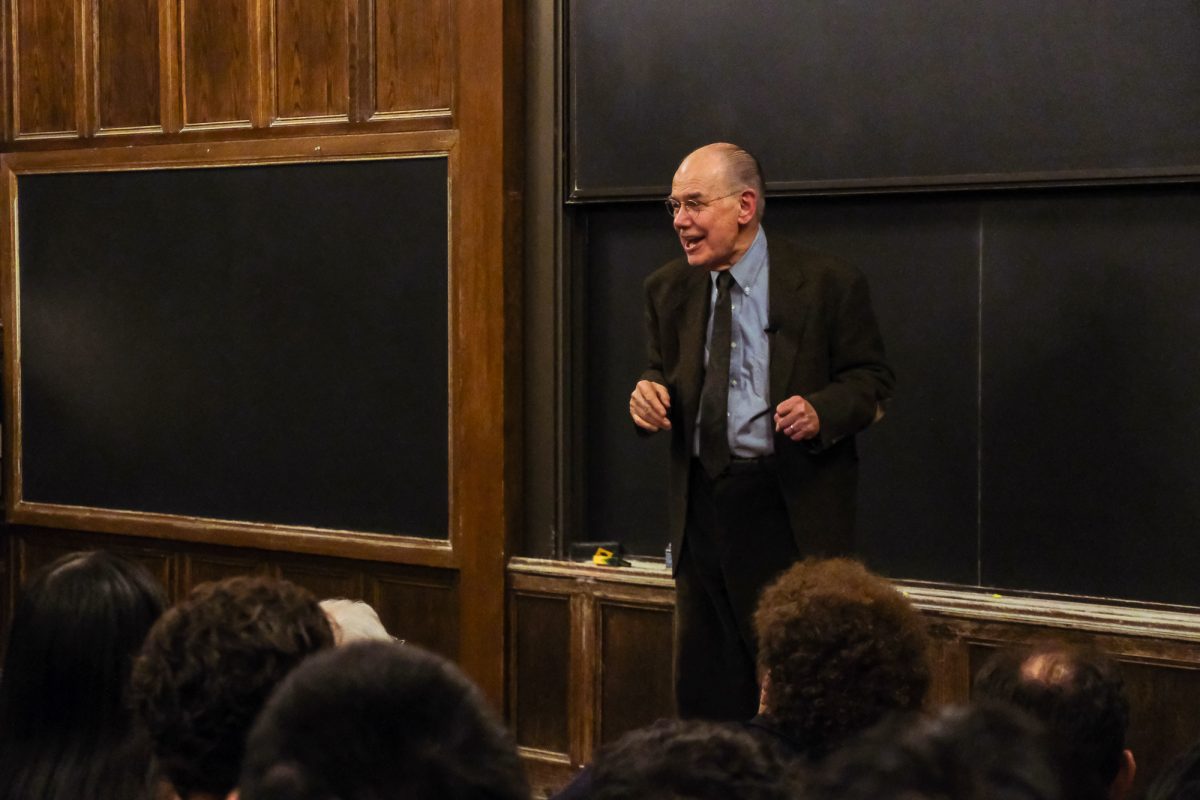

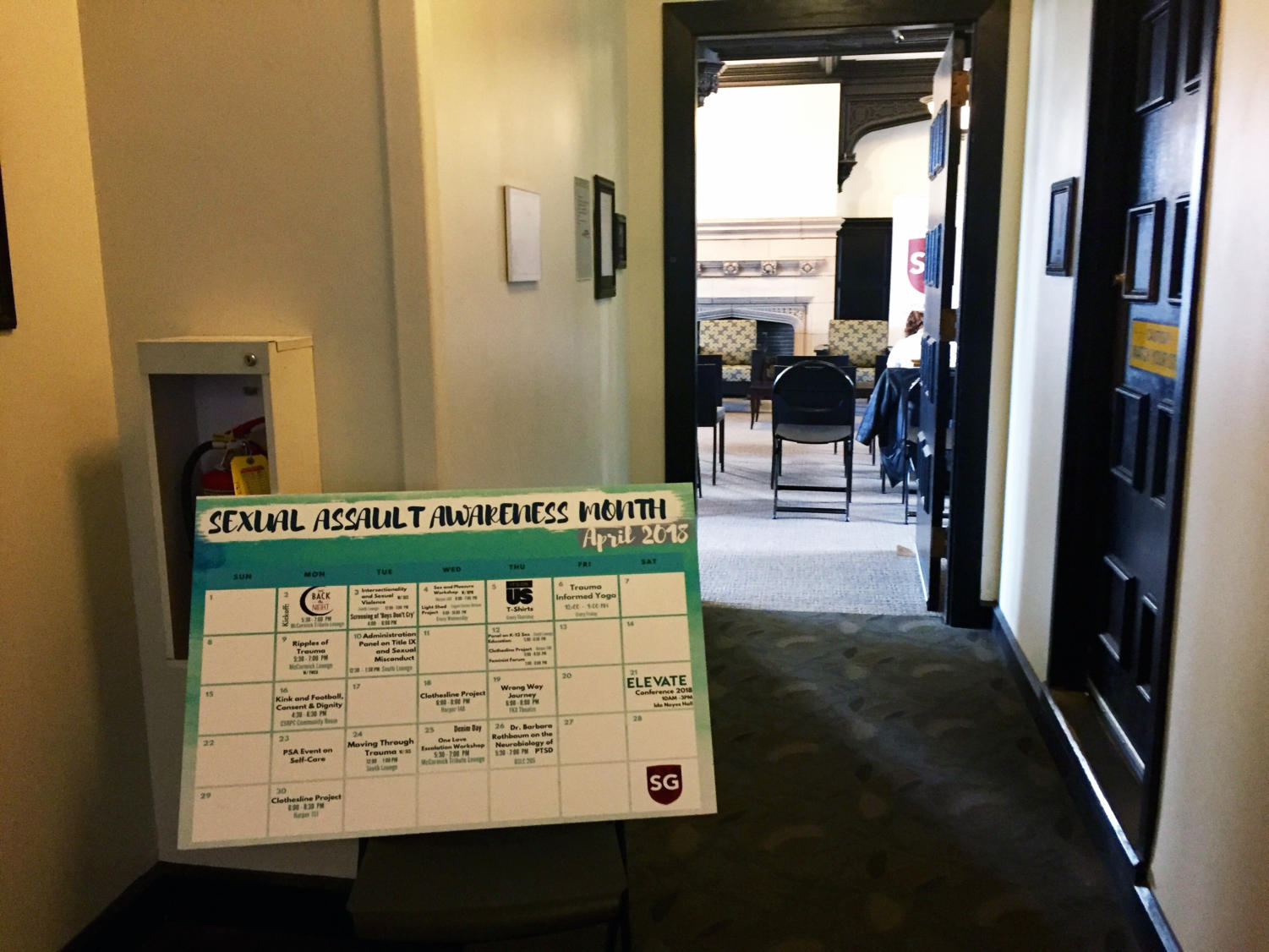

Three administrators took questions at a Student Government-sponsored panel last week on Title IX and sexual misconduct. The panel was part of programming around Sexual Assault Awareness Month (SAAM) and featured Title IX Coordinator Shea Wolfe, Associate Dean of Students Jeremy Inabinet, and H. Barrett Fromme, an associate professor of pediatrics and a chair of the University-wide Student Disciplinary Committee.

The speakers opened the panel with a brief overview of their respective roles and how to communicate with their offices about sexual misconduct. They spoke to more recent University initiatives surrounding sexual misconduct and emphasized themes of transparency, consistency, and accountability.

Administrative Action

Associate Dean of Students Jeremy Inabinet outlined the basic setup and procedure of the Disciplinary Committee, which is composed of 34 students, faculty, and staff. On this committee, students apply to serve one-year terms (with the option to be reappointed) and interview with the provost.

Staff serve three-year appointments (with the option to be reappointed) and are appointed by the provost based on recommendations from the Dean of Students in the University.

The provost solicits and appoints faculty members to serve three-year appointments. Fromme is one of three University-wide committee chairs. When a complaint reaches the hearing phase, typically five of these committee members attend the hearing: 3 faculty, one staff, and one student.

According to Title IX Coordinator Shea Wolfe, however, the procedure currently allows for this committee to comprise a minimum of three faculty and any combination of staff and/or student.

Wolfe acts as the first point of contact for many students. She reviews reports from students, student leaders (like RAs), and disclosures from “responsible employees.” Wolfe explained that she provides students with a one-page summary of support and resources at their first meeting, including a flowchart illustrating the University response to student disclosure of sexual misconduct.

If Wolfe does not hear back from a student within approximately one week after initial contact, she reaches out to the student again via e-mail with an informational letter and the same one-page summary.

Wolfe reiterated that her office allows her to help students coordinate academic and housing support, referrals to medical and law enforcement professionals, no-contact directives, and more. Wolfe often mediates many subsequent communications with relevant administrators “so that students don’t have to share their stories several times.”

“We take a trauma-informed approach,” Wolfe said.

Available Services on Campus

Wolfe highlighted Sexual Assault Deans-on-Call, Student Health Service (SHS), Student Counseling Service (SCS), and ordained religious advisors as confidential resources for students.

Wolfe said she has recently seen a “significant increase” in student accommodation requests and more reports of sexual misconduct in general, which she attributes to greater degrees of outreach and education.

Following the 2015 campus climate survey, which asked students about sexual misconduct and resources, the University has spearheaded several new initiatives. These changes include a “support person” initiative, which ensures that someone is always available to accompany students in meetings with Wolfe, should they desire.

These seven individuals have undergone at least eight hours of training, and an eighth individual is in the midst of training now, according to Wolfe.

“Under this initiative, trained faculty, other academic appointees, and staff are available to serve as support people during student disciplinary matters and can provide emotional and personal support during any administrative or formal process,” Associate Provost Bridget Collier and Dean Michele Rasmussen wrote in an e-mail to students last month.

At Tuesday’s panel, Wolfe stressed that there is no “expiration date” for students seeking resources. Students, for example, can seek University assistance two weeks or two years after an incident of sexual misconduct.

Moreover, she noted that students who meet with her are not automatically forced to pursue a disciplinary process. In fact, Inabinet does not receive information provided to Wolfe, even if the student chooses to pursue the disciplinary process, unless expressly requested.

“The same types of resources are available to respondents,” Wolfe said.

Wolfe chairs the Sexual Misconduct Student Advisory Board, which includes 15 students from the College, graduate divisions, and professional schools who serve as liaisons between the Office of the Provost and students.

The board meets twice-quarterly. Since last year, Wolfe, along with Inabinet, has also been working with Phoenix Survivors Alliance (PSA), which requested quarterly meetings with the administrators to discuss student concerns.

The Disciplinary Process

Students usually meet Inabinet, associate dean of students in the University for disciplinary affairs, to request certain restrictions for another student’s actions. Given that members of the disciplinary committee rotate, Inabinet said he is concerned with maintaining a “consistent and uniformly informed” reporting process, working off of a checklist whenever meeting with students to that end.

Once a student has reported, the respondent typically gets one week to meet in person with Inabinet to discuss the process and the respondent’s experience with the reported behavior. Inabinet then reviews the case with a faculty chair and decides whether or not the case will proceed to a hearing.

“Our threshold for that [decision] is pretty low,” Inabinet said.

Inabinet requires both parties to write out a statement for the five-member committee one week prior to the scheduled hearing. Inabinet meets with the students in advance to help them get familiar with the room where the hearing will take place.

Students may choose from several “degrees of participation” at the hearing: in person (with complainant and respondent separated by a curtain), via Skype, and more. Inabinet noted that one student even communicated with committee members via a support person, who donned a headset and relayed questions on the student’s behalf.

The panelists said that most students opt to be present at the hearing. Even so, the students involved never enter the room at the same time but are “staggered.”

“Through our process, our complainant and defendant never ever see or speak to each other,” Inabinet said.

In some cases, the University may not be the only channel through which students handle these events. Some may pursue criminal charges against a respondent, which may result in its own set of legal procedures.

“We’ve had students sue each other for defamation,” Inabinet said.

Fromme, a University-wide Disciplinary Committee chair, explained that the committee meets before a hearing to review proper questioning procedure.

Fromme noted that the committee operates off of a script when conducting hearings for consistency’s sake. After the questioning period, students have eight minutes for closing statements.

Although the committee strives for unanimous rulings, Fromme said, only a 3/5 majority is required.

“We’re always guided by policy and whether or not that policy was violated,” Fromme said.

If the committee reaches a decision before 4 p.m., students are emailed that day. However, decisions coming after 4 p.m. are not released until the following morning to ensure that resources a student might need are available.

Students receive a formal letter articulating the committee’s rationale within one week of the hearing.

To sanction a student in any way, the panelists explained that they take five main questions into account:

- What was the policy that was violated?

- What was the impact on the complainant?

- What evidence is there to determine a threshold for action?

- What community considerations do we have?

- Did the respondent have any awareness of their actions?

“We’ve never had anyone say they are responsible,” Fromme said.

The committee’s sanctions could range from the revocation of a degree to an official warning. Most sanctions feature a combination of several options.

“Additional sanctions in addition to what is listed could include a warning, unilateral no contact directives, restrictions to/from (RSO participation, building access, University events, University programs), and removal from housing,” Wolfe wrote to The Maroon in an e-mail.

The speakers also explained what happens should a student wish to appeal their decision. An appeal request, Inabinet said, needs to identify one of three things: a procedural error, new information, or proof of a disproportionate sanction. This appeal would then proceed to a “review committee,” composed of three disciplinary committee members who were not involved in the initial hearing.

Wolfe noted that this entire process is only four years old. Inabinet said that the committee is currently in discussions for drafting a mechanism for removing a Disciplinary Committee member from the committee.

Student Concerns

In the Q&A portion of the event, one student asked the panelists about their perceived misconceptions surrounding campus resources.

“An individual’s personal experience belongs to them,” Inabinet said, adding, “but that experience doesn’t speak for everyone.”

Another student asked the panelists if there are ways to shorten the duration of the disciplinary process, referencing the added stresses that this process can have on complainants.

Inabinet explained that the process usually doesn’t take longer than 60 days from complaint to hearing. Moreover, Inabinet said that his office has been setting hearing dates even further in advance, to give students a concrete end point for the investigation.

Wolfe clarified this timeline in an e-mail to The Maroon: “Students have three times in the process when a face-to-face conversation is necessary. The initial interview (which varies in time based on the details of the information present), the pre-hearing meeting (an opportunity to have the hearing process explained, in detail, and to be able to see the hearing space. This lasts about 30 minutes), and the hearing (which typically lasts one to two hours, depending on the complexity of the information).”

One student asked if Wolfe’s office will comply with potential policy changes under President Donald Trump’s administration.

“We’re adhering to the interim guidance for now, and no University policies have changed,” Wolfe said, adding, “At this point in time, we’re waiting to see what the policy recommendations are.”

In September, U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos announced interim guidance for investigating campus sexual misconduct under federal law. Some have expressed concerns that, under the new administration, the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) could reverse policies initiated by its 2011 “Dear Colleague Letter,” which mandated that federally funded universities use a lower standard of proof known as a preponderance of evidence in adjudicating sexual assault cases. Tuesday’s panelists said that they anticipate further information from the OCR in the coming months.

Student Solutions

While University administrators work to improve their approach to sexual misconduct on campus, some students have taken the matter into their own hands.

Fourth-year Sarah McNeilly, who attended Tuesday’s event, is currently writing her public policy B.A. thesis on possible improvements to the University’s sexual misconduct policies.

“Viewing UChicago within the constraints of bureaucratized higher education, I’m kind of looking at: Where do issues of institutional accountability fall? What are the greatest challenges to the administration? And how can we move forward?” McNeilly said, adding, “A big part of what I’m trying to do with my thesis is making sure that the recommendations that I provide are practical and feasible.”

For her thesis, McNeilly has met with six University administrators directly involved with programming and policies surrounding sexual misconduct. She told The Maroon that she plans to meet with one more administrator this week before submitting her thesis, which will propose recommendations to the administration. While some recommendations will include policy changes, she noted that other improvements run a gamut from program funding to redesigning marketing strategies.

“There have been a lot of campus movements over our four years here. In The Maroon, you’ll see a lot of critical editorials and think-pieces that end by offering policy recommendations,” McNeilly said. “The goal of my thesis was to take a very measured, data-driven approach to what should be the next steps forward.”

In January, PSA launched a campaign to amend the University’s Policy on Harassment, Discrimination, and Sexual Misconduct, calling on the administration to increase transparency.

“We have found that these policies are not only inadequate, but executed in ways that seriously compromise the rights and health of survivors on campus. This is evidenced both by the testimonies of numerous survivors and by close review of UMatter, the University website intended to provide information to students about these two policies, and of the policies themselves,” it read.

Then, in February, Student Government’s College Council voted unanimously to approve a statement in agreement with PSA’s proposed changes to the University’s policy.

Meanwhile, first-year Malay Trivedi is organizing a conference to address sexual misconduct policies at colleges and universities across Illinois, scheduled for November 9 in Ida Noyes Hall, 8 a.m.–6 p.m.

“The conference has two main goals: inviting students from all around Illinois and the Chicagoland area to talk about best practices—what kinds of initiatives they have started, what the results have been, and what has been successful. So a lot of that is about organizing and campaigns that are student-run,” Trivedi said.

The collaborative nature of the conference will facilitate Trivedi’s second goal: drawing on lessons learned from the conference to draft an open letter to state officials.

“I’ll be authoring an open letter to both the governor and attorney general of Illinois essentially describing how we as students need to see state law shaped in order to continue to protect us during what can only be described as a flux in federal law at the moment, as we don’t know what the new draft regulations by the Office of Civil Rights of Betsy DeVos will be. It’s essentially just a preemptive case about working with state government so that we will continue to have provisions in place for students,” Trivedi said.

Several members of PSA and Resources for Sexual Violence Prevention (RSVP) have joined the conference’s planning committee, Trivedi said.

The event itself will begin with a keynote speaker, followed by a series of breakout sessions. These sessions might delve into topics such as how Title IX affects minority groups, or how best to partner with university administration to combat sexual misconduct, Trivedi said.

“With something like this that has taken hold of national discourse and has really become more evident in recent times with, say, the Time’s Up and #MeToo movements, I just felt that it was important that we take an active stance to do anything and everything that we can to solve this problem now,” Trivedi said.

Not including event organizers and Maroon reporters, four students attended last Tuesday’s panel.

Sexual Assault Awareness Month (SAAM) will continue throughout April. Shea Wolfe will be moderating Student Government’s “One Love” workshop on April 25. Her office hours are Tuesdays 11 a.m.–2 p.m. For anyone interested in participating in Trivedi's November conference, please find more information here.