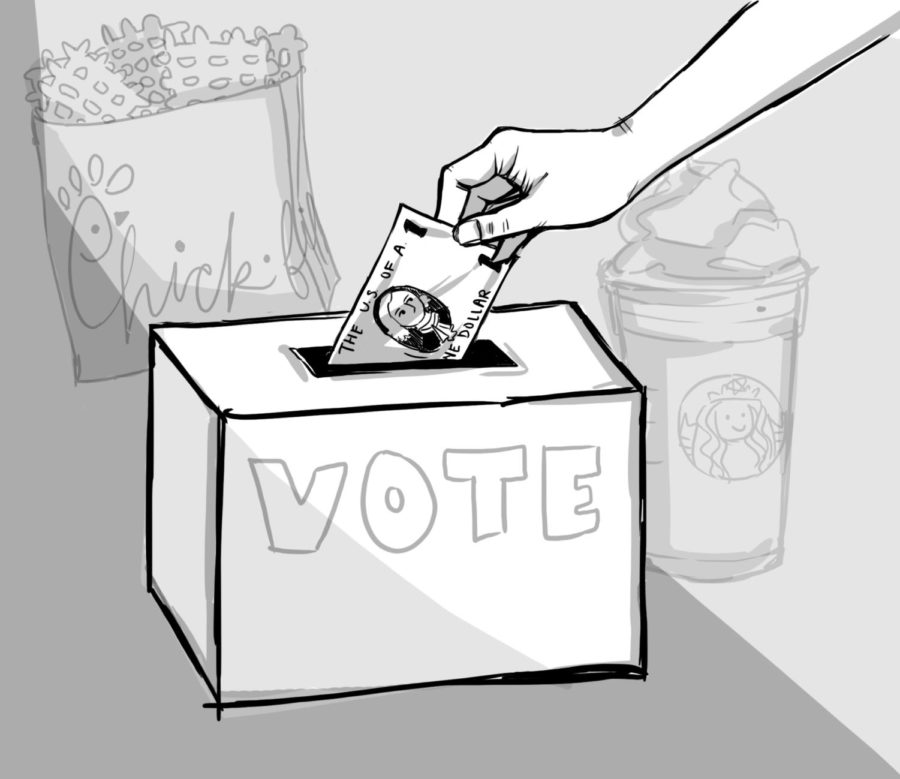

There’s absolutely nothing new about the idea of “voting” with your dollars. Consumers have long threatened companies with desertion or boycott for unsavory political stances or acts. This tactic has been wildly successful at times—the Montgomery Bus Boycott, beginning in 1955, is one of the most notable examples.

Recent history abounds with instances of consumer retaliation. After Parkland, gun control advocates boycotted advertisers and retailers that were too cozy with the NRA or too willing to stock certain guns. And gun rights advocates retaliated, boycotting pro–gun control restaurants and eliminating a $40 million tax break for Delta after the airline shelved an NRA discount that only 13 passengers had ever used. Insufficiently Christian coffee cups are an affront to some caffeine addicts; racist coffee servers are equally galling to others. Donating to PACs and other groups with a political bent is always a risky maneuver for retailers.

Modern examples of “dollar voting,” however, have evolved a great deal. Today, boycotts and consumer desertion no longer represent just reactions to something a company has done, but opinions on what they should do. Consumers don’t just retaliate against companies for what they believe are incendiary political stances or acts. Instead, people demand active political stances from ostensibly nonpartisan institutions, like ordinary workplaces, retailers, and major universities. The rise of these moral demands goes to show how even routine affiliations have themselves become increasingly political acts.

Eating, for instance, has become a curiously partisan endeavor. It isn’t simply that you might have felt obliged to snub Chick-fil-A in 2012 for its CEO’s comments on gay marriage. The “kiss-ins” and boycotts that followed were reactive; they represented a more conventionally political response to an offensive stance.

Today, however, you might eat at Chick-fil-A—or perhaps not—because of the basic “Christian values” system it promotes. Chick-fil-A is well-known for its religious bent; they close on Sundays to allow employees to go to church, for instance. Its corporate purpose states that it aims “to glorify God by being a faithful steward of all that is entrusted to us and to have a positive influence on all who come into contact with Chick-fil-A.” If that lofty ideal seems mostly irrelevant to sandwich sales, apparently you’re missing something key in the intersection of God and the poultry industry.

Although less in your face, plenty of other establishments have used savvy marketing to link their brands with inclusive values and tolerance, or else with some America First sensibility. In either case, the values mostly have nothing to do with the products themselves.

Although the racist expulsion of two black men several weeks ago is a prominent exception, Starbucks has a long history of marketing itself as a bastion of liberalism—from creating refugee hiring programs to supporting baristas’ college ambitions to openly marketing books on mass incarceration. And you would have had to be living under a rock to have missed the furor that accompanied Target’s gender-inclusive product labeling.

Even though these companies often take stands on issues central to their field, it’s not always about the coffee or the toddlers’ toys or whatever other product is ostensibly at stake. Chick-fil-A doesn’t simply facilitate church attendance for employees. Rather, it makes a point of telling you, the potential consumer, that this is something it cares about. The same is true with Starbucks’s book choices. These moves represent calculated signals to and for consumers: It’s OK, you’re buying evangelical chicken. Or, that Venti latte is for Bernie supporters with strong opinions on the tax bill.

In some sense, we should welcome this insistence on bringing our values into our daily lives. We’re right to think that we should act on the ideas we espouse, that we make grand principles real by dragging them down from their lofty abstractions to the gritty business of our day-to-day lives.

Although our moral demands reflect a welcome focus on the profound implications of our “boring,” routine affiliations, they can go too far. Responding to others is one thing—our desire to react to stances we find offensive can be admirable and just. Few would contest the idea that when possible, you should avoid financing “evil.” But we can veer into risky territory. We don’t actually gain much when we insist on bringing out a full-fledged value system every time we open a wallet; we might, however, add to our existing divisions.

This isn’t even to mention the absurdity of pitching “family values,” for instance, in fast food, retail, or any service industry. Why should I have to choose between pious and open-minded chicken? What are you gaining when you suss out the implied ballot choices of a cup of joe? It’s raining and late, your car needs gas, and you find an intersection with a BP gas station on one corner and a Marathon station on the other. What sort of due diligence are you required to conduct before picking one? Do you have to review their corporate mission statements? Track down their political donations?

That particular kind of moral demand adds little to our lives and risks sorting us further into strict partisan bins. I don’t want my choice of food chain to tell you anything about what I believe. It won’t actually change those positions. (Who on Earth has ever been converted by a sandwich?) It probably won’t materially support those positions, either—although companies routinely make political donations, the process by which your coffee funds a campaign is arguably more shadowy, objectionable, and self-serving than it is high-minded. In the rush to be virtuous buyers, we can easily become over-obsessed with our gratuitous, empty signals about the people we think we are. That’s what bumper stickers—not coffee choices—are for.

Natalie Denby is a third-year in the College majoring in public policy studies.