The heavily publicized Harvard admissions trial surrounding race-based affirmative action policies wrapped up this past Friday, but the case—and the issues it poses—are far from resolved. Regardless of the decision, which is expected to be released in early 2019 and will likely be appealed to the Supreme Court, there will be far-reaching effects throughout the world of highly selective college admissions, a world that includes UChicago.

This case is deeply personal to me. I am Asian American, the demographic at the forefront of this current push to end race-based admissions and the racial group perhaps most conscious of the possible injustices of affirmative action policies. I submitted applications to multiple highly selective schools, Harvard included, and received a slew of rejection letters. I have, at times, felt frustrated by the way in which college admissions seem to give people who look like me such short shrift.

That being said, I don’t believe that ending race-based affirmative action is the proper way to address the existing issues with college admissions, issues that include a lack of transparency in the system, the usage of personality-trait tests easily subject to racial stereotyping, and the reality that certain qualified students are not given a chance, simply because of their race. Race-blind admissions, the solution that Students for Fair Admissions advocates, is not the answer. No matter what we might want to believe, race matters. Race has always mattered. As a minority, it is a fundamental part of my identity, something inextricably bound to who I am and what I have experienced. To ignore that part of me, as Harvard alum Sarah Cole so eloquently stated in her testimony, “is an act of erasure.” If colleges truly want to look holistically at all of their applicants, if they truly want to foster diversity on their campuses, then they must take race into account.

Much of the anger surrounding race-conscious admissions policies seems to be severely misplaced. Many Asians and Asian Americans who are campaigning against affirmative action direct undue blame toward Black and Hispanic applicants, arguing that it is those students, many of whom are viewed as under-qualified, who are taking spots away from ostensibly more deserving Asian Americans. Indeed, throughout both the trial and news coverage of the case, the statistic that Asian Americans need to score hundreds of points higher than Black and Hispanic applicants on the SAT in order to receive the same admissions consideration has been heavily emphasized. While these numbers are true, and unfortunately so, it is sobering to see them used as a basis for such a cynical story. Black and Hispanic students, despite the benefits they might receive from affirmative action, are still underrepresented across the board at elite, highly selective universities.

By ending affirmative action in its current form, by eliminating race entirely from the admissions equation, the Asian admit rate will certainly rise, but the white admit rate will rise as well, at the expense of every other minority group. Some in the Asian-American community may still see this as a win, but a win for Asian Americans at the expense of Blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities is not a win worth celebrating. Not when, at the end of the day, white privilege will again be affirmed. Asian Americans, despite their anger, cannot allow themselves to become pawns in a white man’s game.

None of this is to say that the anger is unwarranted. While the arguments made by the Asian-American groups spearheading the case against Harvard often feel simplistic and off-the-mark, there are real issues at play that Asian Americans should be angry about. It is frustrating to see Harvard employ a personality scale on which Asian Americans score markedly lower than any other demographic group, despite the fact that interview impressions are roughly equivalent. It pains me that former MIT Dean of Admissions Marilee Jones would label a Korean-American student as “yet another textureless math grind.” It makes me angry that a system designed to lift up underrepresented minorities, to combat systemic racism and oppression, seems to actively flatten the Asian-American applicant, ironically perpetuating the tired, racist trope that “all Asians are the same.”

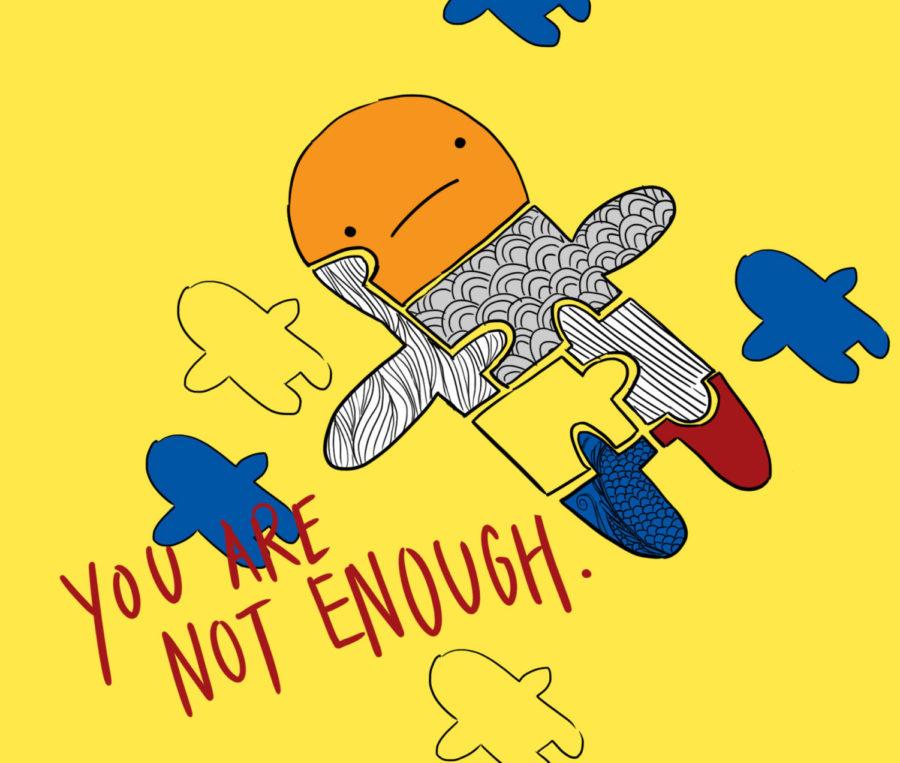

I think that all Asian Americans who have applied or are applying to college, particularly elite, highly selective colleges, have felt acutely conscious of their Asian-ness and of all the stereotypes and burdens that come with it. When I was in high school, preparing to start my applications, I was very aware that my race would be seen as a strike against me. And for me, it hurt, not so much because I was afraid of rejection, but because it felt like, in this moment where we were all being judged, all the self-doubt, all the identity struggles, all the small confusions that come with growing up Asian in America were being hammered into me yet again. But this time, the same message I had heard for so much of my life was practically being shouted by the very gatekeepers of privilege: If you are Asian, you are not enough.

It made me bitter that nothing I was doing seemed to matter. I cared about school, I liked learning things, but it felt like the more I worked to get the grades I wanted, the more I became just another typical Asian robot in the eyes of society. And it was infuriating that colleges seemed to reward Asians for being “different,” as if it were somehow an insult to be likened to other Asians, fueling the self-hate that already permeates the Asian-American community.

Affirmative action is complex and engenders similarly complex problems, ones that don’t present easy solutions. While race-conscious admissions practices can at times play into painful stereotypes, race-blind policies are misguided, wayward stabs at an answer. But what other solutions are there? And will those solutions be measurably better than what we have now? Perhaps these issues will never truly disappear. Perhaps we, as a society, simply place too much faith in our elite educational institutions. But amid these uncertainties, one thing is for sure: College admissions will change, and those changes, for better or for worse, will alter the future of privilege in America.

Lucas Du is a second-year in the College.