The University’s biological sciences graduate program in June removed the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE) admissions requirement across all graduate programs, at the urging of the Graduate Recruitment Initiative Team (GRIT), a student organization that advocates for diversity and inclusion.

Since its founding in 2016, GRIT has seen its membership skyrocket. It currently counts over fifty members spanning the Biological Sciences Division (BSD), which houses 16 graduate programs totaling about 400 doctoral students and admitting about 75 students annually for Ph.D. study. GRIT also recently expanded into the Physical Sciences Division (PSD), recruiting for the mathematics and chemistry departments.

In June, following the College’s announcement that it would go test-optional and no longer require candidates’ SAT or ACT scores, GRIT sent an open letter to BSD faculty asking graduate programs to follow suit and drop the GRE.

For over 80 years the GRE has been used as the standardized test admissions requirement of choice for most graduate schools in the United States. According to parent organization Educational Testing Service (ETS), the exam measures verbal and quantitative reasoning, analytical writing, and critical thinking skills.

Urging faculty to remove the GRE requirement from applications to the division, GRIT cited studies that “have highlighted the exam’s bias against minorities, women, and persons from low socioeconomic backgrounds.”

UChicago GRIT students spearheaded the removal of the GRE Requirement from the Biological Sciences Ph.D application. If you’re interested in how we did it, stop by our booth (816 & 818). #SACNAS2018 pic.twitter.com/9pHoJqWhCN

— UChicago Graduate Recruitment Initiative Team (@UCGRIT) October 11, 2018

Within four days of sending out the letter, the organizers learned that the division had agreed to drop the GRE requirement, GRIT cofounder Cody Hernandez, a Ph.D. candidate working in molecular genetics and cellular biology, told The Maroon.

While the College made headlines as the first top research university to go test-optional for undergraduates, UChicago’s BSD was joining a growing slate of institutions, including University of California–Berkeley, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University, and Stanford University, that have opted to remove the GRE requirement in recent years.

This shift in admissions requirements follows a change in national standards for science funding: In 2015, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that it would no longer require GRE scores in applications for fellowships and training grants.

The NIH decision, in turn, came seemingly in response to an influential article by physicists Casey Miller and Keivan Stassun, published in Nature in 2014. The article argues that admissions committees’ reliance on the GRE metric “severely restricts the flow of women and minorities into the sciences.”

Referring to data from ETS, the article notes that in the physical sciences, women score 80 points lower on average than men, and Black people score 200 points below white people.

“In simple terms, the GRE is a better indicator of sex and skin colour than of ability and ultimate success,” Miller and Stassun conclude.

In conversations with The Maroon, GRIT organizers echoed these views.

“The GREs are not predictive of how you’re going to succeed in graduate school. The only thing that it holds any correlation to is how rich, white and male you identify as,” Selina Baeza-Loya, GRIT’s current director of recruitment, told The Maroon.

GRIT’s Inception and GRE Removal

Initially, GRIT organizers focused on attracting underrepresented minority (URM) students to apply to the University of Chicago, traveling to national conferences and research fairs to recruit potential candidates.

The organization’s cofounders were familiar with literature arguing that the GRE is biased against URM students, and in 2017 floated the idea of removing the GRE admissions requirement, bringing it up to Victoria Prince, dean of graduate affairs in the BSD. At the time, they were told there simply was not enough departmental support.

Just a year after GRIT’s unsuccessful first venture, however, the College announced that it would drop the SAT/ACT requirement for undergraduate applicants. GRIT seized the moment to make their case again.

“The political climate had changed—GRIT was now an officially accepted thing—and also, GRIT was included in a lot of these training grants, now. So GRIT had a lot more leverage,” said GRIT cofounder Mat Perez-Neut, a Ph.D. candidate in molecular epigenetics. While the timing was key, he added, “there was still a lot of resistance.”

Although their proposal to drop the GRE passed the second time, “one-third of the faculty members were opposed to eliminating the GRE,” Perez-Neut told The Maroon. “I was actually surprised that two-thirds wanted to remove it…. I think a lot had happened that really changed the culture to allow for something like this to occur.”

Prince told The Maroon that GRIT’s efforts helped the department rethink its skepticism toward dropping the test.

“When we thought about it last year, people thought there was still some value in the number, even though they understood that it’s a bit of a flawed measure, that has some links with socioeconomic group rather than being anything close to an IQ test. But they thought, ‘there’s still a bit of signal there.’ So it took that additional pushing from the GRIT students and from a careful evaluation of the literature,” she said.

Reasoning Behind GRE Removal

Graduate departments that have removed the GRE requirements have noted the poor performance on the test of women, students who are from low-income socioeconomic backgrounds, and URMs. Studies of the exam have also found that the GRE is a poor predictor of admitted students’ academic outcomes, and many opponents of the test argue that admissions committees should instead favor a holistic analysis of interviews, research experience, college GPA, and letters of recommendation.

Prince told The Maroon that a “subliminal stereotype threat” accounts, in part, for racial and gender disparities in GRE performance. Stereotype threat refers to a finding in social psychology that individuals who belong to negatively stereotyped groups perform worse on tests due to anxiety, widening the achievement gap between different groups.

She said that departments at other universities have tried various approaches as they struggle to achieve diversity in their programs.

“The physical sciences in some schools have decided to just weight the scores differently for male and female candidates, because there’s so much evidence that in more quantitative testing, women don’t do as well, and yet when they get into the program, they do fine. So rather than not use the test, they’ve decided to actually give kind of different weights,” Prince said, noting that this strategy is “also an imperfect approach.”

Leading up to the GRE’s removal, Prince said, she had the Graduate Education Advisory Committee, a faculty group, “drill into the literature” on the lower exam scores of female and URM students. They found that the literature supporting a positive correlation between GRE scores and student outcomes in graduate school is often flawed.

“There could be some signal there, but it’s really no better than GPA, and we’re still using GPA,” Prince concluded.

The dean also stressed that the GRE does not measure soft skills like students’ perseverance and commitment to research.

“It’s really difficult to assay whether stronger performance in classes correlates with stronger research performance, and just anecdotally, it probably doesn’t,” she said. “And GRIT have pointed out that tenacity is—as their name suggests—is a key element of success.”

GRIT also had an early ally in Nancy Schwartz, dean and director of postdoctoral affairs. The group emerged out of the Initiative for Maximizing Student Development—an NIH grant Schwartz oversaw—and students continued to work closely with Schwartz and other administrators in the Office of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs.

For Schwartz, GRE elimination has been a long time coming.

In the ’90s, she and several other University faculty members in the sciences set about examining best practices in graduate education, including the GRE, and quickly “realized it was a pretty bad test,” she told The Maroon. After she and four other faculty members met with administrators from ETS, Schwartz was invited to sit on the board of the GRE, where she subsequently served for four years.

During Schwartz’s tenure on the GRE board, she and other members successfully pushed to revise the exam, removing archaic vocabulary requirements. They wanted to go further, pushing to replace the current model of a general GRE and subject tests with a field-specific GRE designated for graduate students in the sciences, but were unsuccessful.

Still, Schwartz is glad that biological sciences departments at top research institutions are beginning to drop the GRE. “It does not measure persistence, it does not measure innovation, it does not measure creativity—all of the kinds of things you need, at least in the sciences, to be successful in graduate school,” she said.

Admissions, Yield for URM Applicants

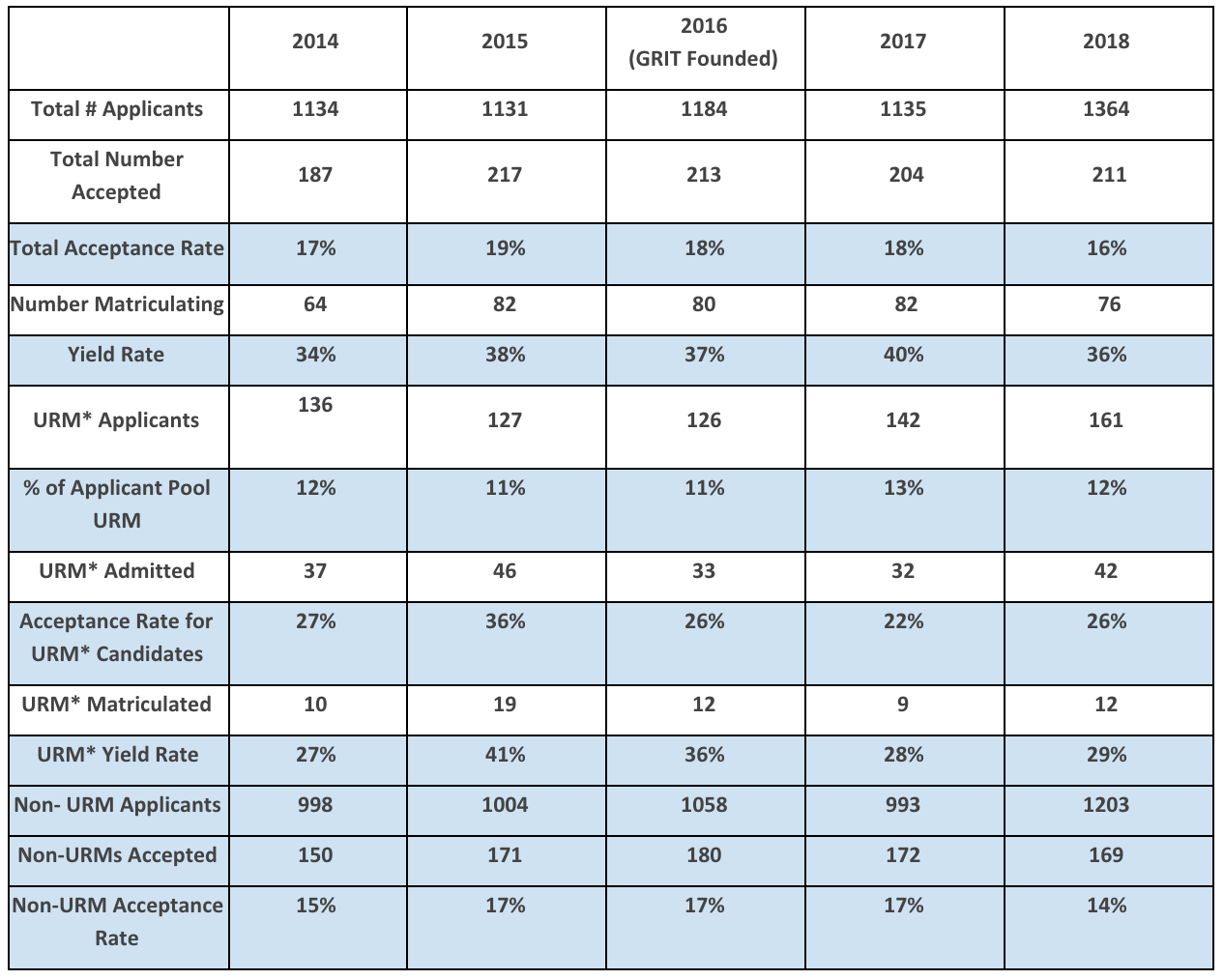

*The BSD relies on the NIH definition of Underrepresented Minority (URM): “Blacks or African Americans, Hispanics or Latinos, American Indians or Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders.” This designation is limited to US citizens and green card holders. 'Non-URM applicants' therefore refers to international applicants and domestic applicants who are not members of a URM group.

Admissions data for the past five years, provided to The Maroon by Prince, reveals a consistently higher acceptance rate for URMs than for non-URM applicants, and, meanwhile, a lower yield rate for URMs than overall.

While the actual number of URM candidates has increased, the percentage of URM applicants hasn’t budged, just kept pace with a growing total application pool. Still, Prince and Schwartz emphasized that they consider any increase in URM applicants to be a victory for GRIT, given the challenges of attracting URM candidates.

“These days, with the pressure we’re getting from NIH, everybody is searching for enhancing the diversity on their campus, and so the recruitment of these kinds of individuals is very intense right now,” Schwartz told The Maroon.

GRIT attributes the recent boost in URM applicants, in part, to their model of active recruitment at research fairs. GRIT students accompany admissions representatives like Schwartz on trips to recruitment fairs, approach prospective applicants and, if they seem interested, put them in touch with UChicago faculty in their field.

Hernandez said putting prospective applicants in touch with faculty boosts their interest in UChicago: “If we plugged them in with at least two faculty, they were almost guaranteed to come here.”

Prince concurred, saying GRIT’s efforts “have made the difference in encouraging people who have offers to actually come.”

Still, administrators continue to hope that GRIT and similar initiatives will boost the URM yield rate.

“Our current conversion rate from applicant to matriculant is not where we want it to be,” Schwartz acknowledged.

In this PowerPoint slide from a departmental presentation, provided by Dean Prince, “Percentage of URM’s admitted” corresponds to underrepresented minority students who were recruited by or in contact with GRIT.

GRIT in 2017 recruited or had contact with about 40 percent of the admitted minority students; this past year, 80 percent of admitted URMs had contact with GRIT. Over the same two cycles, the number of URM applicants increased from 32 to 42 people, and the number matriculated into the class went from nine to 12.

It’s unwise to draw conclusions about general trends from such a small sample population, when each admitted class has fewer than 100 students.

Prince acknowledged the challenge: “We had a terrific matriculation year back in 2015. To some extent, it’s about laws of small numbers—I think we kind of hit lucky that year. But it does show that we have always been making strong efforts, because this predates GRIT.”

Prince noted that top schools compete to attract talented URM candidates—”it’s almost like an arms race,” she said.

Asked about the URM yield rate, which dropped from 41 percent in 2015 (before GRIT’s founding) to 28 percent in 2017—a data point that could just as easily suggest GRIT caused fewer URMs to join—Prince attributed the dip to competition with other leading research institutions and said she believes the number is coming back up “because we’re doing something new and better.”

Beyond recruitment at research fairs and hosting inclusion events, GRIT organizers would like to see more direct student input as candidates’ applications are reviewed.

Baeza-Loya, the current director of recruitment, told The Maroon that starting this year GRIT is piloting a model for student advisors to work with faculty admissions committees.

Using the biophysics graduate program—which has seniors sit as full-fledged members of the admissions committee—as a model, GRIT is piloting student advisor positions on several programs, including neurobiology, according to Baeza-Loya. The students will not have direct say in admissions decisions, but would act in an advisory capacity.

“When faculty hire new faculty, they get to choose their own peers. Why can’t we, as graduate students—long term inhabitants of this community, this University—why can’t we also have a greater amount of say in who joins our graduate programs?” Baeza-Loya said.

Gender Parity and Expansion Into Physical Sciences

Getting the GRE dropped from the BSD was just one component of GRIT’s organizing work. In addition to URMs, GRIT advocates for women and LGBTQ+ people, and just started a team focused on students with physical disabilities.

Within the BSD, admitted students have averaged 52 percent female over the last five years. Gender parity “has not been a problem in our field for many years,” Prince said, noting one exception: the medical physics program, where students are drawn from a background in physics, rather than biology, and the applicant pool has averaged 20 percent female over the past five years.

More recently, GRIT expanded into the Physical Sciences Division (PSD), where in addition to minority underrepresentation there is a significant gender disparity. This year, GRIT organizers began recruiting students for math and chemistry Ph.D. programs.

Leaders of GRIT were initially hesitant to expand the program to the PSD.

In the biological sciences, the NIH sets national benchmarks for diversity, attaching grant money to inclusion initiatives to ensure that departments are making efforts to support underrepresented groups in science. Physical science funding, by contrast, comes from the National Sciences Foundation, and grant requirements are rarely tied to diversity efforts, meaning GRIT leaders have struggled to find “leverage” in making the case for departmental change.

“If the NIH says, ‘you need to have diversity programming or you’re not going to get your money,’ that’s really motivating, real quick, for a lot of people,” Baeza-Loya explained.

Perez-Neut said he was therefore surprised when Emily Easton (A.M. ’01, A.B. ’01), then the associate dean of students in the PSD, urged him to consider expanding GRIT to the PSD. Despite the lack of funding pressure, he says he’s met with “heartening” support for diversity efforts in the PSD.

“In the physical sciences, those pieces of leverage don’t exist, and if they do we don’t know what they are. So there’s a lot of goodness in working in the physical sciences…. Everyone involved is doing it because they want to do it,” Perez-Neut said.

GRIT cofounder Christina Roman, a Ph.D. candidate in biochemistry and molecular biophysics, worked with Easton and the PSD to help GRIT expand into the physical sciences. Roman stressed her excitement that the new generation of GRIT leadership is primarily women, saying, “I love being able to guide them through the special challenges that come with being women in leadership positions in science.”

Linsin Smith, GRIT’s current director of retention, told The Maroon the group’s immediate goal in the PSD is to demonstrate that GRIT’s recruitment and retention activities can increase the number of underrepresented applicants that matriculate into math and chemistry.

“I think once we can show how impactful the work GRIT does will be for the PSD, we’ll be able to expand to the rest of the programs in the PSD and also from there can start having conversations with admissions committees and the deans about potentially dropping the GRE as a requirement,” Smith said.

As GRIT continues its efforts in the BSD and beyond, organizers stressed the importance of sustainability, noting that many graduate diversity and inclusion initiatives fizzle out as soon as leaders graduate. To ensure that GRIT is around long term, organizers have split the codirector position into two roles—director of recruitment and director of retention—and stipulate that no individual can serve in a leadership position for more than one year, predicting that consistent turnover will keep the organization’s survival from becoming too dependent on any one person.

Meanwhile, while Hernandez and Perez-Neut are no longer directors, they continue to work with GRIT in an informal role and are hoping to expand the model to open GRIT programs at other university campuses. They are currently in talks with the University of California–San Francisco and the University of Virginia (UVA). At UVA, they recently facilitated a dialogue between students and faculty modeled on similar forums they’ve hosted at UChicago.

Hernandez said that the GRIT model provides both students and faculty with an “open platform” to discuss concerns.

“This hasn’t been a one-sided thing—students are critiquing the faculty about their shortcomings, but faculty are also providing students with feedback so that they can also help their relationship with the faculty. So, the system works because it’s equitable, and it removes the power dynamic,” Hernandez said.

It remains to be seen whether dropping the GRE—or, for that matter, the SAT and ACT for the College—will drastically increase the number of applications to the University, further driving down acceptance rates that have plummeted in the past decade.

“I don’t know whether it is going to influence the applicants—whether applicants are going to be more prone to applying to those schools that have dropped it, and therefore their applications are going to skyrocket. That we don’t know until we see what happens,” Schwartz said.