A visitor entering the Stony Island Arts Bank might be surprised by the content of its latest flyer. The simple black-and-white fold page prints out not a curatorial text, but 10 registers of “What We Want Now!” The list runs from freedom to “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, JUSTICE, PEACE and people’s community control of modern technology.”

The 10 Point Program of the Black Panther Party provides a common theme for the collective exhibition, ICONIC: Black Panther, which invites artists to interpret the “fifty-plus years of the Black Panther Party.” Diverse in their material and style, the artworks revolve around issues and experiences pertinent to black and marginalized communities. From police violence to joblessness, the exhibition, as the Black Panther Party (BPP) did, tackles grave injustice through the entangled lenses of race, class, culture, and gender.

In the late 1900s, the BPP answered injustice with radical self-determinism. Conceived after the assassination of Malcolm X, the BPP expanded his message and used militant action to achieve social advancement for Black communities and the proletariat. The BPP most memorably set up free breakfast programs for school children and patrolled Black neighborhoods to prevent police violence, using extra-governmental spaces to help marginalized people. In Illinois, the chapter chairman Fred Hampton organized five breakfast programs and free clinics, reaching out to local gangs to enlist them in the class war. Yet the FBI listed BPP as an enemy of the government, and director J. Edgar Hoover pledged to exterminate it. Hampton was assassinated in his sleep during a raid by the Chicago Police Department and the FBI in December 1969; his death was later ruled to be justifiable homicide by a coroner’s jury inquest.

Among the several works in ICONIC that pay respect to Hampton is a particularly moving piece by local artist Liz Gomez. On two boxes, painted grey to resemble the concrete slabs of a tomb, is Hampton’s most famous declaration, painted in red: “I am a revolutionary.” Flowers frame the words, some wilting, some blooming. The curving petals stand drastically in contrast with the blunt, monotone boxes, evoking at once the ardor of life and the impenetrable seriousness of death. Bridging the two is the slogan painted in red, dripping like the blood Hampton died bleeding. To face the piece is to stand face to face with the dead, recognize the history of oppression that led to their murders—which lives on today—and realize the firm necessity for revolution.

[photo id = 54486/]

Several works indeed directly address current political issues. Amanda William’s “Uppity Negress” juxtaposes, on a long piece of black cloth that hangs from ceiling to floor, the recording from Sandra Bland’s arrest and a speech made by Michelle Obama. Bland, who was pulled over after a traffic violation, explains solemnly why she seemed irritated and repeats “you do not have the right” to the police arresting her. On the other hand, Obama’s message is to take criticism and name-calling as “just noise.” As the interwoven words flow down the drape, Obama’s high-brow oration engulfs Bland’s struggling protest. The BPP, unlike the other Black movements of its time, was more occupied with the actual suffering of Black people than their representation in language and culture. As the Obama Presidential Center is scheduled to be built in Jackson Park, this piece holds particular gravity.

The exhibition itself echoes the call to action. The lack of gallery text leaves the visitor space for individual interpretation, and two rows of sofas carve out space for conversation in the center of the exhibition. In collaboration with the Illinois Black Panther chapter’s celebration of its 50th anniversary, the Stony Island Arts Bank has programmed events that include conversations with existing BPP members, film screenings, and community gatherings. The BPP is also resurrecting clinic drives testing for sickle cell disease, along with other survival programs. Part of the proceeds from works sold at the exhibition will go to helping BPP members still imprisoned.

[photo id = 54487/]

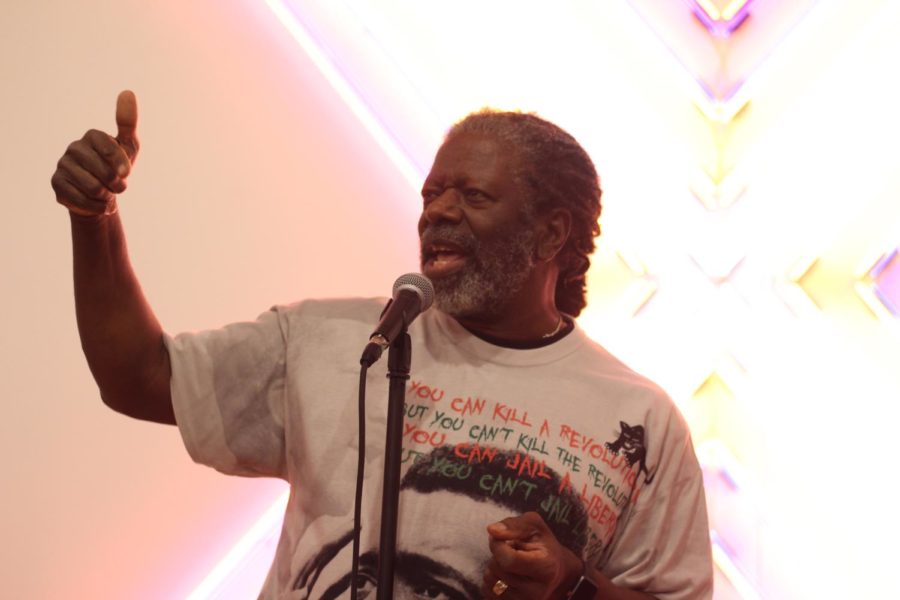

“Who does the art serve?” asks Emory Douglas, whose quotes dot the walls of the exhibition. The former Minister of Culture of the BPP spoke much about how art must serve the people. “The art we were making transcended the Black community and became iconic for communities interested in social justice all over the world,” one quote reads. An icon becomes an element of society because it propels, unites, and mobilizes people; iconic art extends beyond observation and critique. It offers itself as an actor within social movements. Perhaps this is why the 10 Point Program is printed on a flyer. Instead of resigning to the language of galleries, ICONIC: Black Panther inserts itself into the continuous fight for justice and peace.