It is tragic that Measure for Measure is one of Shakespeare’s lesser-known plays, because it is one of his funniest works. Both a genuinely thought-provoking experience and a masterpiece of bawdy humor, Measure is full of sexual innuendos and cheeky puns. While the Bard’s signature lowbrow moments are amusing, the play’s plot and the moral quandaries it raises makes the Dean’s Men production worth watching.

Vienna has become degenerate, and its ruler Duke Vincentio (second-year Sam Jacobson) decides to address the problem. His plan for doing so, however, does not actually involve him taking any responsibility (for that would make too much sense)—instead, he runs off and leaves Lord Angelo (first-year Liam Flanigan) to rescue the city from its depravity. His choice to entrust Lord Angelo with the task lies in the latter’s moral austerity, which is so great that it is said that “when he makes water, his urine is congealed ice.” The new deputy does his job and makes fornication illegal, to the great indignation of all the prostitutes in Vienna, as well as to Claudio (first-year Justin Saint-Loubert-Bie), who is arrested and condemned to death for impregnating his mistress Juliet (second-year Matilda Kupfer). Claudio’s friend Lucio (first-year Franziska Harling) alerts Claudio’s sister Isabella (second-year Sabrina Sternberg), an aspiring nun, about her brother’s situation. Whatever will she do?

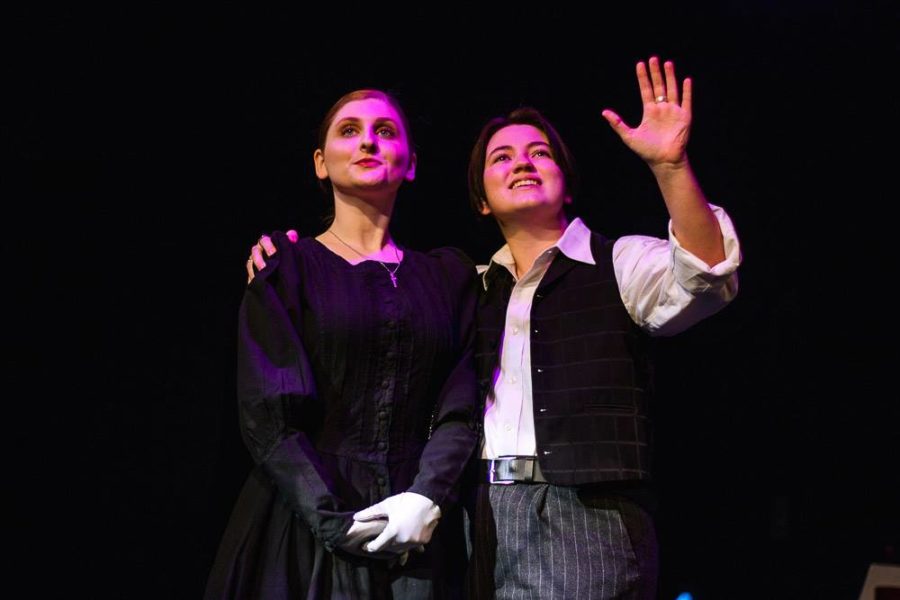

The Dean’s Men production was originally intended to take place during Prohibition, but they ultimately decided to move the setting back some 40 years to the 1890s. I was initially skeptical about this change, but the shift in era ended up providing an opportunity for some wonderful costume design that would have been lost in a later adaptation. In fact, the entire show is visually compelling: The dim atmospheric lighting combines with impressive set pieces to take the audience through dank prisons, seedy bars, and imposing seats of governmental jurisdiction, and reflects not only the physical setting but also that scene’s tone and emotional significance for the characters inhabiting it.

Director third-year Sophia Lubarr focuses on the play’s humor as much as its seriousness and atmosphere, a choice which provides some much-needed relief from the direness of Isabella’s situation. Especially funny are the cocky and messy Lucio and the cackling, knife-wielding executioner Abhorson (first-year Natalie Chapin).

The more serious parts of the play were equally captivating. Isabella is a difficult role to play—the character must plead to Lord Angelo for her brother’s life and then suffer under his ultimatum: give herself over to his lust, or allow her brother to die. Sternberg does the role justice, giving scope to all of Isabella’s conflicting emotions and portraying them extremely persuasively. Her pain is palpable, and she is as dignified and graceful while also being defiant. Flanigan, meanwhile, is cold and convincing as Angelo, and Jacobson brings a considerable amount of humor to his depiction of Duke Vincentio. Laughing at the ridiculousness of Vincentio, one can almost forget that Jacobson’s character might be just as morally reprehensible as Angelo.

This possibility reveals itself most clearly in the final minutes of the play. In the original script, Vincentio, after claiming to have aided Isabella in retaining her virginity, exposes Angelo. Then, saving her brother’s life, he asks her to marry him, or, rather, declares that they will be married. However, Shakespeare never writes Isabella a response; in fact, she does not speak for the rest of the play. That moment after the Duke’s proposal is fascinating because it is so open to interpretation—does she implicitly consent by her silence, or does she act in some way beyond what the words in the script say? Is Shakespeare highlighting the Duke’s hypocrisy, or is he simply providing a happy ending for his play? What does Isabella, who never replies, look like after the proposal? Lubarr makes a very definitive and intriguing choice in her adaptation of this part of the play. I will not spoil what that choice is—you shall have to see the show and find out for yourself.