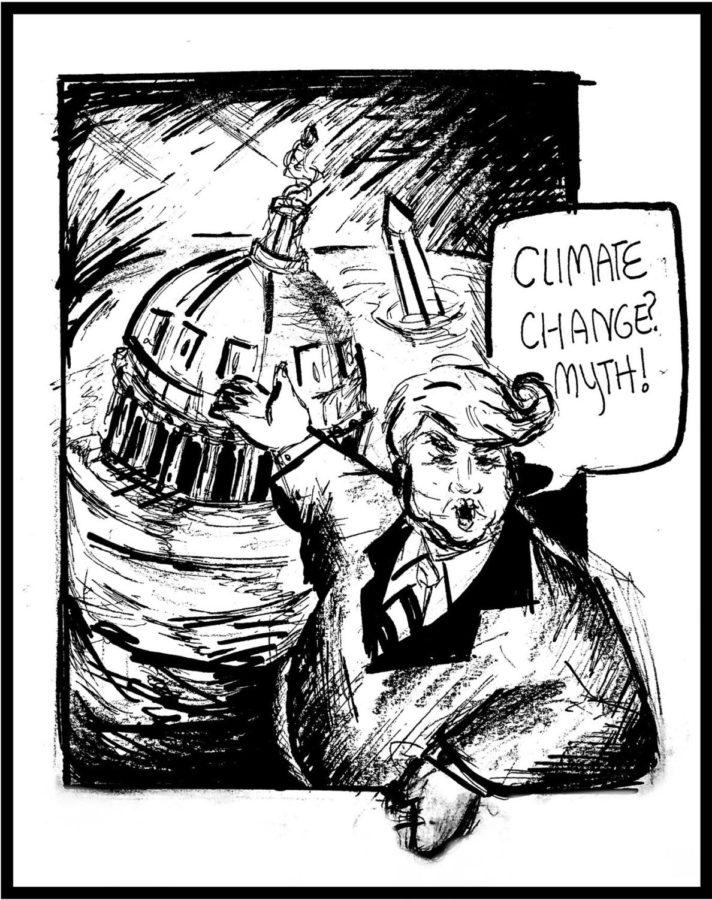

“I don’t believe it.” This was the response President Donald Trump had to the National Climate Assessment released Thanksgiving weekend. The document, drafted by 13 of Trump’s own governmental agencies, is scientists’ latest, hoarse-throated warning cry: If significant changes aren’t made to address climate change, there will be severe consequences. This isn’t a matter of belief; it’s a matter of fact.

Trump isn’t the only one plugging his ears to science, however. A 2017 study found that 13 percent of Americans don’t believe the earth is warming at all, and a staggering 87 percent aren’t aware of the overwhelming scientific consensus that mankind is the main cause of global warming.

So what does this mean for those of us who do believe in climate change? At a time when the effects of global warming are becoming visible in the U.S. (see California, which recently had its deadliest fire in recorded history), there is a pervasive feeling of hopelessness. The weight of this makes complacency easy—it is tempting to simply try lessen our own environmental impact (when convenient), and pretend we aren’t participating in an inherently un-eco-friendly system. However, if we are to believe the scientists (please do), this is no longer an option. If climate change is to be slowed, we need a seismic restructuring of society— and for this, we have to get organized.

When I was in third grade, I remember being shown an environmentalist video for Earth Day. It was an interview with Nobel laureate and environmentalist Wangari Maathai, founder of the Green Belt Movement. In the animated video, Maathai tells an Ecuadorian fable about a forest fire: The animals of the forest watch it burn from afar, transfixed by the flames engulfing their home, but do not act—all except for the hummingbird. Despite its diminutive size, the hummingbird flies back and forth from the fire to a nearby river, heroically trying to put out the flames drop by drop. “I’m doing the best that I can!” it exclaims. “I’m doing the best that I can!”

Back in 2009, this was an inspiring video to watch. Environmentalism was framed as an individualistic task, one that could be achieved by simply lessening your carbon footprint. Recycle at home! Take shorter showers! Buy a Prius! Surely, we thought, if enough of us hummingbirds filled our beaks with water, the forest fire of global warming could be subdued.

Fast forward almost a decade, and we are only fanning the flames. Among the National Climate Report’s predictions: Our nation’s coasts will flood with increasing frequency, agricultural output may decline to 1980’s levels by mid-century, and the West Coast’s destructive fires will only continue to intensify and expand eastward. The study also provided evidence that the U.S. GDP could take a significant cut by the end of the century if current trends continue—painfully ironic, given that Trump has consistently claimed his pro-fossil fuel policies would stimulate the economy.

Even hypothetically, it’s hard to grapple with the implications these changes would have. Homes would inevitably be destroyed and families forced to relocate; food prices would rise and jobs would be likely be lost. Dismaying though it may be, now that the U.S. has withdrawn from the Paris climate agreement our future could very well be this grim. Anything else will require a serious national about-face, which seems unlikely under an administration that actively supports the fossil fuel industry.

In response to this seemingly immutable reality, many have embraced eco-friendliness on a personal level. The subculture of thrifting has ballooned, the number of vegans in the U.S. has grown by 600 percent over the last three years alone, and reusable straws have become the new canvas grocery bag. All this, I would argue, is just a symptom of the helplessness people feel in the face of an incredibly nearsighted government. Being “green” is empowering; like the hummingbird in the Ecuadorian fable, you feel like you’re doing your part. Unfortunately, there is a complacency latent in this feeling. If you’re already “doing your part,” what moral obligation is there to do more?

In the context of today’s political-scientific divide, I look at the hummingbird fable in a much different light than I did a decade ago. It’s all well and good that the hummingbird is doing its best to help, but there’s an urgency that 9-year-old me didn’t recognize: Unless the other animals pitch in, the forest is still going to burn down.

It would be easy to blame the other animals for the forest’s fate. Certainly, had they joined the hummingbird rather than stood motionlessly by, the forest could have been saved. The elephants in particular we might hold accountable, because for decades their whole party has successfully convinced other animals that there’s a raging debate over whether the forest is actually on fire at all.

Yet it was the hummingbird who knew how to respond; it was the hummingbird that in this life or death situation could have tried to educate or organize the masses. Instead, it just “did its best,” while the forest burned down around it.

There is something to be said for doing the best that you can in a broken system. If everyone makes an effort to lessen their own carbon footprint, our collective footprint will indisputably be smaller. There is inherent value in this, but it simply isn’t enough. In a world where 70 percent of carbon emissions come from just 100 companies, “going green” on a personal level is a hummingbird-sized drop in the bucket.

What we need is organization on a national scale, and rallying cries to reflect it. Help educate climate change skeptics! Campaign for environmentalist candidates! Protest corporations that refuse to limit the use of fossil fuels! If we want a chance at avoiding the future laid out by the National Climate Assessment, we must do more than profess the ideals of environmentalism—we must demand reform, reusable straws clenched in our raised fists.

Maya Holt is a first-year in the College.