While today, fetal ultrasounds are a common sight on social media and in popular visual culture, this has not always been the case. As a new exhibit in the Special Collections Research Center explains, at one point in history, the fetal image had to literally be kept under lock and key in the back of medical textbooks.

The Fetus in Utero: From Mystery to Social Media presents a timeline of the fetal image, including three distinct time periods characterized by representational shifts and technological advancements in the techniques used for printing these representations. The exhibition is not only a story about the fetus, but also one about the creation of a visual culture, and the precarious border between the medical, the social, and the artistic.

The exhibit was curated by Margaret Carlyle, a postdoctoral fellow at the Stevanovich Institute on the Formation of Knowledge, and UChicago Medicine physician Brian Callender. The co-curators aimed to “bring art and science back together…. It’s become clear that the fetus has been medicalized in obstetrics and gynecology, and there’s a whole other artistic side of representing the body. And in a way, we’re sorting of bringing them back together,” Carlyle said.

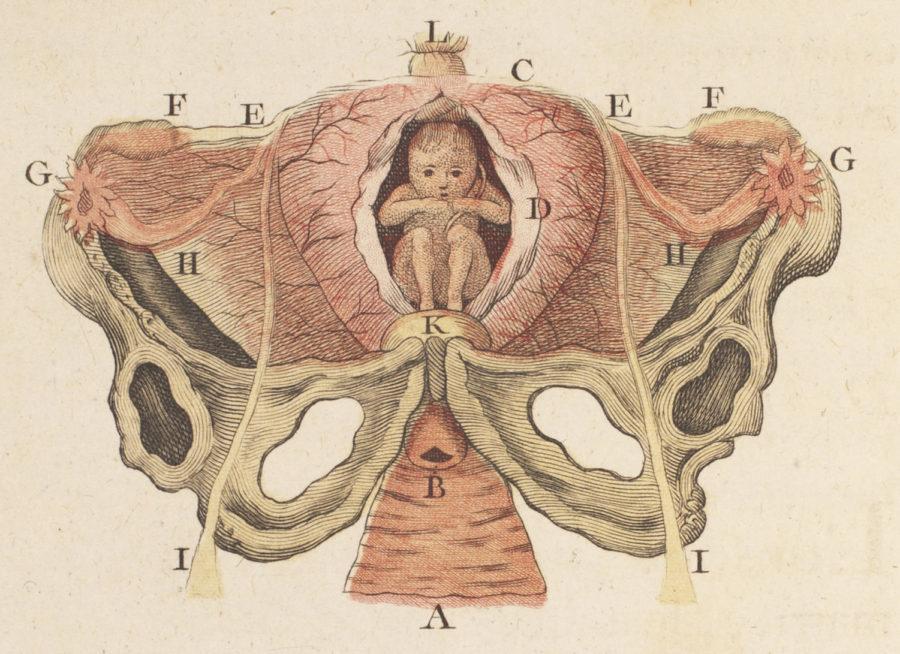

This is especially evident in the first and second sections of the exhibit. The first traces the fetus from 1450 to 1700, a period when images of the female body were few and far between and the representation of the fetus in utero relied on dissections of deceased pregnant women, a controversial practice often considered morally wrong. The images that did permeate early medical resources toed the line between artistic depictions of women’s capability to generate life and the beginnings of a coherent obstetrics medical practice.

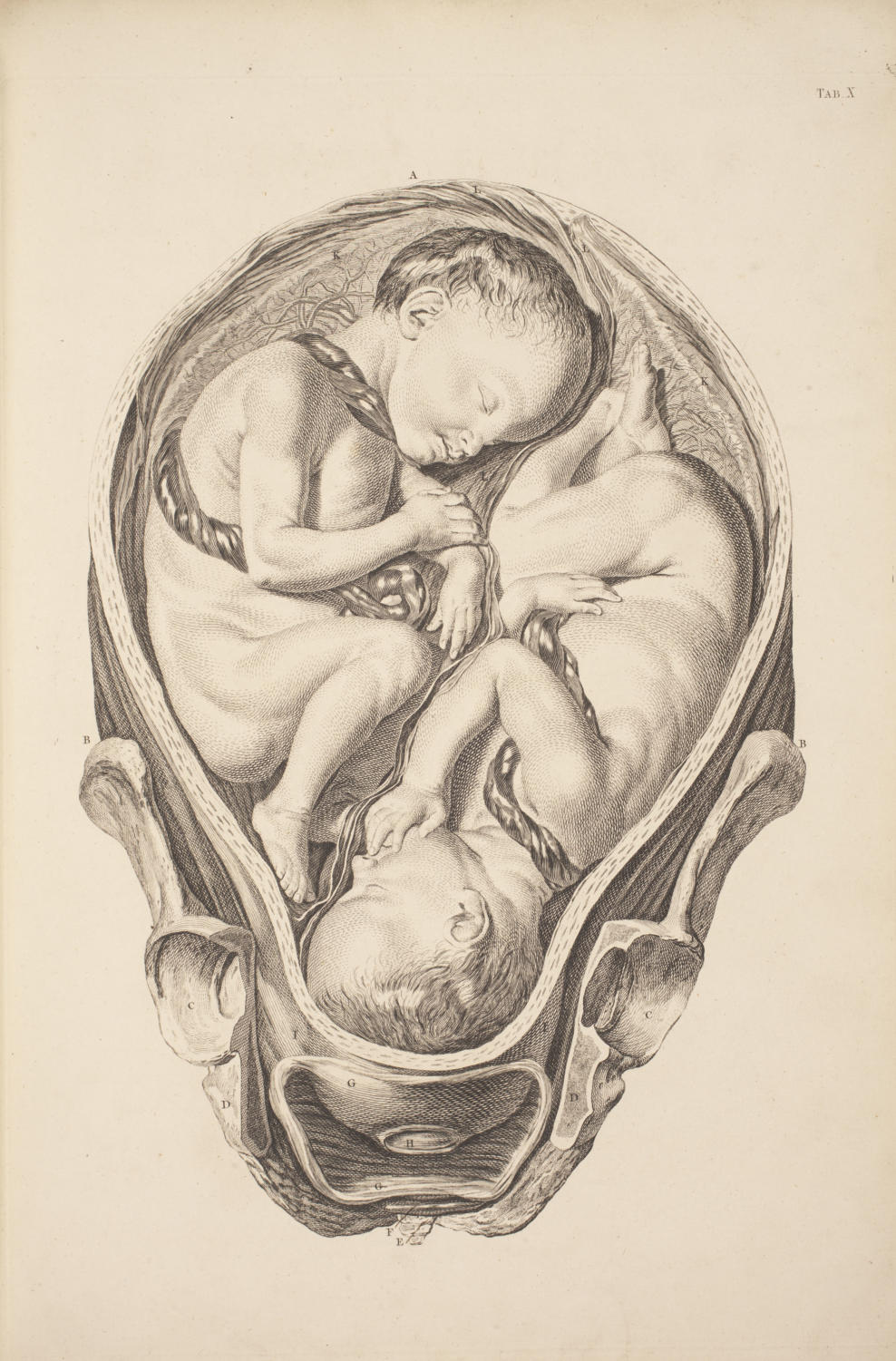

As the exhibit moves to its second epoch (1700–1965), the depictions it highlights are more widely reproducible, but also more localized in medical textbooks. The pictures of this period betray the paradigm shift in thinking of birth as generative to focusing on reproducibility.

Unlike the first and second periods of the exhibit, which demonstrate a gradual visual evolution, the third one has a clear catalyst. A 1965 cover of Life magazine features a fetal ultrasound and reads “Drama of Life Before Birth.” This would, the curators said, perhaps be the first time most Americans would have any idea what a fetus looked like. Following the Life cover, the exhibition displays the extension of fetal imagery to mass visual culture—a Volvo ad shows an ultrasound and asks, “IS SOMETHING INSIDE TELLING YOU TO BUY A VOLVO?”

For an exhibit that bases its main narrative on the visualization of women’s bodies, women’s agency and voice are noticeably absent from much of The Fetus in Utero. This is to no fault of the curators, who have taken measures to draw attention to this and to include resources that highlight women’s voices such as midwives’ manuals from the 1600s. While not explicitly presenting a feminist critique of these various representations, the two are quick to point out the various ways that medical textbooks and educational materials (historically the only sources of this kind of representations) contribute to women’s exclusion.

While we look at one of the touchstone pieces of the collection that features a completely disembodied uterus set atop stumpy, chopped off legs, Carlyle remarks, “in the Renaissance one, the mother looks almost like a Venus, like a statue. But now, she’s being cut out altogether. Because now we only need to show the interaction of the fetal skull and the pelvic bone, because that’s what’s causing all the problems.” Callender adds, “they get cleaned up some, so they become useful from a clinical perspective as well as an educational perspective.”

Ultimately, though, the curators do not claim an explicit political agenda. They note that during the curation of the exhibit, Carlyle gave one of her classes the chance to write analyses and captions for the various items, which generated a variety of perspectives. In the end, the exhibit asks us to engage not only with the iconography of the fetus that we have normalized, but also to make our own judgements and decisions about what the varied role of this visual schema might be.

The exhibition is free and will remain open until April 12, 2019.