Just over a month ago, The Art Institute of Chicago presented the Roger Weston Collection of ukiyo-e paintings, which span a large selection of 17th to 19th century Japanese art, including portraits of bijin (beautiful women), which were the main focus of the exhibit. As I walked through the labyrinthine gallery, the aesthetics of each meticulously decorated wall scroll, the exaggerated details of the bijin’s kimonos, and the changing motifs of beauty standards —from simple gowns in the 17th century to longer noses and lopsided posture in the 19th— followed me. In a time choked with political oppression, it appeared to me that this artistic trend was a way of celebrating freedom of expression in media. The mission of the gallery was to show off the allure of Japanese art culture. Particularly jarring were the 10-foot-long scrolls depicting various sex positions and the Hundred Beauties exhibit, which portrayed “ugly” prostitutes sucking on animal bones and grinning wildly on the floor. Yet, despite being anomalies in terms of “female beauty” in the gallery, the attention to detail painstakingly poured into the works held true to the theme that Weston wished to give to Art Institute visitors.

And perhaps this was the missing link that visitors failed to detect: that these anomalies carry hidden messages of the sociopolitical history behind the entrancing, elegant imagery. Some are explicit in the facial expressions—a prostitute grimaces in pain as she claws at what appears to be a smoking injury on her arm—and others are far subtler—a courtesan, embroidered by gold paper and poetry written in scripted font, seductively glances behind her shoulder, as if “asking for it.” Texts within the gallery noted that many of these ukiyo-e paintings were commissioned to boast the beauty of ladies of high courts as well as lower-class courtesans, but who commissioned these paintings of the courtesans?

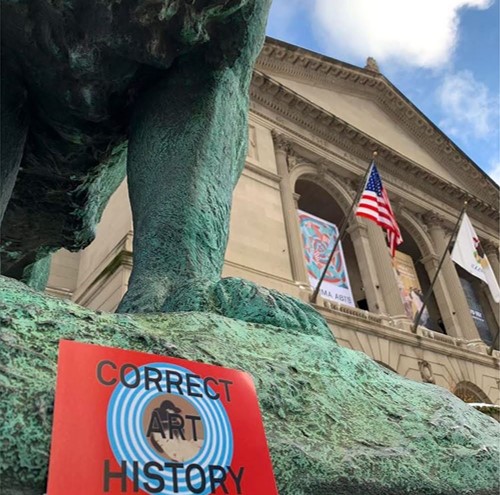

A local Chicago artist, Michelle Hartney, was quick to notice how the museum “failed to contextualize the realities of the courtesans.” In a protest at the Art Institute, Hartney played her alternative tour audio for passing guests, which she has since uploaded on her SoundCloud. Spurred by the #MeToo Movement, the audio tour takes a feminist approach to guiding viewers through the politically charged images of the courtesans and “lowly” prostitutes. Although not arguing against the exquisite beauty of the bijinga (paintings of beautiful women), Hartney explains what she believes the museum insufficiently explicated: the grim exploitation and miserable lives experienced by these lower-status women.

Many of these prostitutes, sold into pleasure quarters as children through indentured contracts, were victims of physical abuse, sexually transmitted diseases, starvation, and forced isolation. The recording features an interview with Dr. Amy Stanley of Northwestern University, who explains how images of the bijinga were commissioned as a marketing strategy, luring men into the Yoshiwara brothels to compete with brothels in more convenient locations. As beautiful women performing various talents in dazzling posters, the bijinga would become a cultural icon of Japan, not only shaping beauty trends—as the Art Institute would underscore—but also encouraging the culture of cruelty against lower-class prostitutes. Hartney asks in her audio tour: “Why do museums hide such tragedies behind the marvels of graceful portraits?”

Upon this advancement, I stared at the ukiyo-e paintings one last time before the exhibition closed. Two scrolls caught my eye in particular: a panoramic view of a Yoshiwara pleasure quarter, and a close-up of two “street-walkers” grinning at the viewer with grotesque, toothy smiles. Neither of them depicts the malnourishment, fear, or oppression that these prostitutes suffered, a negligence museums seem to play along with that widens the gap in history left out in a celebration of creative freedom during a politically tense Shogunate era. Have these ukiyo-e been glamorized, glossing over something that would tarnish a pleasure quarter’s reputation? Likely. Then why romanticize the images of independent street-walkers as well, who have no affiliation with brothels? Is it bigger than just a marketing strategy, idealizing a beauty standard and sacrificing historical reality in the process? Possibly. These paintings, after all, are commissioned to depict a “floating” world—a transience that encourages bathing in worldly pleasures. The word ukiyo-e itself has been mutated from its origins, a Buddhist term defining the “sorrows of life.” The word ironically censors the sadness of the courtesans behind the smiles, “bedroom eyes,” and elegance.

What of the painting I mentioned prior, the one of conventionally uglier prostitutes kneeling on the floor, licking scraps of meat off of bones? A notable anomaly, it perhaps gives more genuine insight into the miserable conditions of the women’s lives. However, this keynote is otherwise glazed over by viewers, including myself when I first visited, due to the intricacy of the artwork. This artist in particular perhaps would concur with Hartney’s stance: there is more than meets the eye in woodblock paintings, no matter how distractingly alluring.

History is written by the victors, or so the saying goes. Each piece of artwork, each text recorded, each story passed down hides invisible truths between the seams. A second glance at art is always worthwhile. It is true that the subject matter of ukiyo-e is not limited to just bijinga, there being many pieces depicting ghost stories or the heroic stances of kabuki actors, but it is also true that the Art Institute of Chicago did not sufficiently contextualize this part of ukiyo-e history, specific to the tragedies of the courtesans. What we can do in such situations is observe and question while appreciating the evolution of beauty standards, the amount of power and respect these paintings retained in the social atmosphere, and the overall masterpieces that these ukiyo-e paintings are in the art world.