According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a parable is an “allegorical or metaphorical saying or narrative” or a “(usually realistic) story or narrative told to convey a moral or spiritual lesson or insight.” Examples that come to mind are stories like the Prodigal Son and Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Typically, video games would not be categorized with this label.

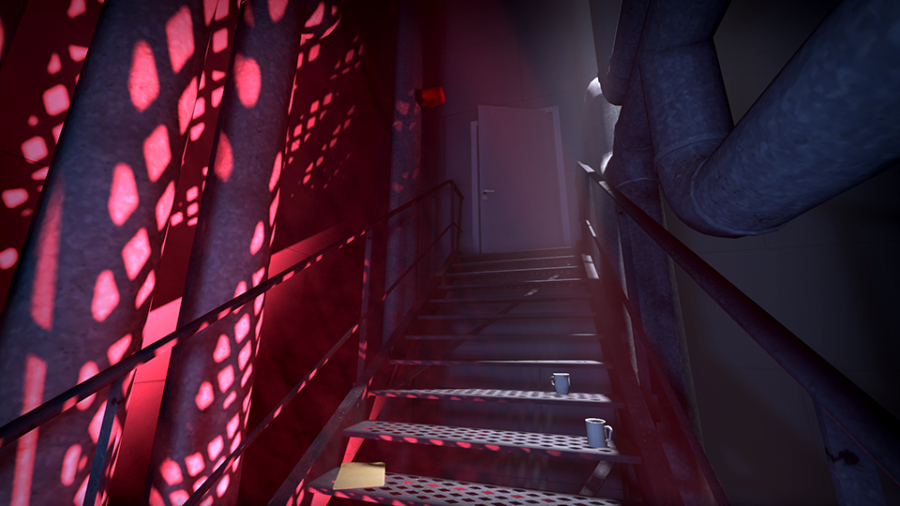

Enter The Stanley Parable by Davey Wreden and William Pugh, a game supposedly about an office worker named Stanley and the day everyone in his office goes missing. It was originally released in 2011 as a mod for Half-Life 2; a remake came out in 2013, and a deluxe edition is slated for release later this year. The game starts with a seemingly standard story arc, but quickly gets more interesting when Stanley comes to a set of two open doors which he must choose between. The narrator (voiced wonderfully by Kevan Brighting) advises the player to walk Stanley through the left door—but you don’t have to listen to him. Listening to or disobeying the narrator while making decisions leads Stanley down a branching tree of strange, absurd, and/or metafictional endings.

That’s where the University of Chicago Philosophy Review comes in. The publication, which runs a blog presenting pieces on various philosophical themes, hosted a playthrough and discussion of The Stanley Parable as part of its ongoing series of events centered around art and media. While UCPR Editors-in-Chief David North and Varun Joshi played the game, professor Patrick Jagoda led a discussion at each junction point about the game and the particular decision in question.

The playthrough worked like this: Every time the player was forced to make a decision, the audience voted for which path to take. The process led to interesting, albeit sometimes inconvenient, results for Stanley. For instance, when presented with the first choice, the two doors, the audience voted overwhelmingly (and perhaps unsurprisingly) to disobey the narrator. This single choice led Stanley down a series of decisions that culminated in one of the longest and most metafictional endings: the “Confusion Ending.” Suffice it to say that to get this ending before any of the other, less weird endings was putting the cart before the horse. For the second playthrough, a consensus formed to heed the narrator’s directions—until the very last choice. While the UCPR had to wrangle with the mercurial nature of the crowd, they rolled with it playfully and this little bit of controlled chaos was fun and informative.

In talking about the game, its endings, and their philosophical significance, Jagoda and the UCPR focused on four questions: (1) What does it mean to make decisions? (2) What is the implied moral? (3) How, if at all, did our own actions contribute to the ending? (4) Do we agree? Having played The Stanley Parable when the remake was initially released, I found these questions very useful to keep in mind while playing. For instance, after a certain point in the Confusion Ending, the player is stripped of all decision-making power (a point accentuated by a pause in the voting system) and even the narrator, who in other endings seems to be in complete control, finds himself unable to “find the story.” Here, as with many of the other endings, The Stanley Parable makes astute commentary with its incisive humor, in this case about expectations of both linear storytelling and player choice in video games.

I’m hesitant to say too much about this game, since it’s much better to play it yourself than to just read about it or watch a playthrough. The UCPR was very clever in choosing to use The Stanley Parable to, as Joshi puts it, “engage people without giving them a Kant book.” The discussions Jagoda led were insightful, clever, and overall fascinating; they reminded me of just how smart and funny this game is. While the event has ended, you’ve still got plenty of time to pick up the source material for yourself or get the deluxe edition when it comes out. You’ll laugh, you’ll scratch your head, and you might just learn a thing or two about the consequences of choice.