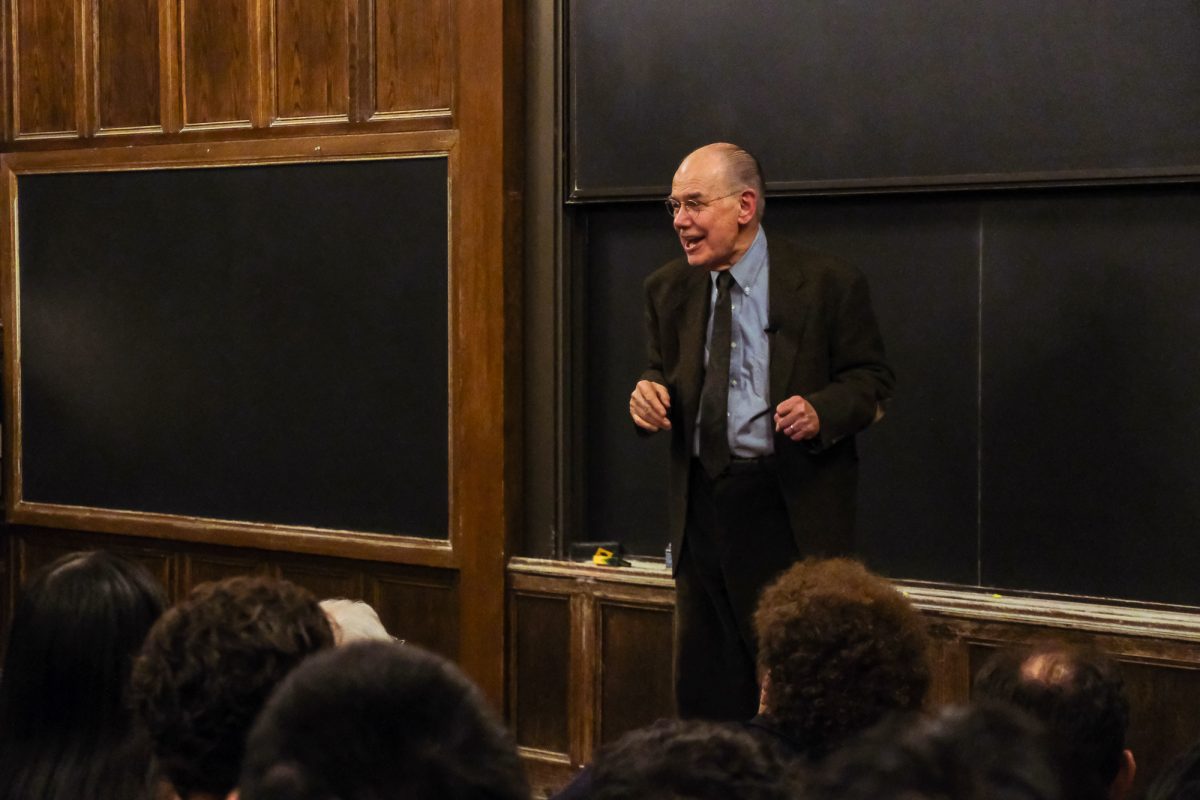

A new book by Harris School professor James Robinson and MIT professor Daron Acemoglu, The Narrow Corridor, discusses the necessary conditions for a society in which liberty exists.

Robinson spoke with The Maroon about the thesis of The Narrow Corridor, namely that liberty is a product of a continual tension between the power of state and society. If state overwhelms its society or vice versa, he said, liberty will evaporate.

“If you toggle too far in one direction, the state dominates society, like in China; then liberty disappears,” Robinson said. “But on the other hand, in large parts of the world, you could say society dominates the state…. In Yemen, for example, there is very little in the way of an effective central state and that turns out not to be a situation with very much liberty either.”

Robinson was adamant that world events did not motivate him and Acemoglu to write The Narrow Corridor, despite the theory’s current applications. They had been thinking about working on this book even before the 2012 publication of their last project, Why Nations Fail.

However, he did characterize the contemporary moment in developed countries as one of “intense realignment,” due to increasing inequality and political polarization in developed countries.

He referenced the election of Donald Trump and Britain’s impending departure from the European Union as symptoms of this realignment, which is taking place at a pace faster than what governmental and cultural institutions are able to handle.

“Donald Trump, for all his eccentricities, was able to latch onto this discontent about the way things have been going, and this massive neglect of large parts of the U.S. population, particularly in the Midwest…. In some senses, the change has run ahead of the ability of institutions to cope with it. And the institutions need to catch up,” Robinson said.

“I think chasing current events is a very bad way to do academic research,” Robinson said. “The book is trying to provide a way of understanding long-run political dynamics in society [and] a much more detailed theoretical foundation for a lot of the ideas we discussed in our previous book.”

While The Narrow Corridor does include a chapter that explains how populist ideology fits into their theory, Robinson stressed that “that’s definitely not the focus of what we’re doing.”

What they are doing—“thinking about the differences in human societies”—is the result of multiple disciplines and approaches. Robinson and Acemoglu are both economists, but their work includes methods from math, anthropology, statistics, and history as well.

In Robinson’s words, “If you want to understand developing problems in the world, large bits of what’s relevant…is completely absent from economics. We’ve always looked elsewhere to try to understand what is it that’s missing and how is it that you think about that.”

Robinson said that many economists are motivated by problems or puzzles inside their field, and contrasted that with his and Acemoglu’s interest in the problems they saw around them. Fieldwork and methods from other disciplines are essential to their research. Using only economic methods and theories could result in an under-conceptualized conclusion, he said.

Robinson offered Marx as an example of how “what masquerades as general social science is actually very tied to specific historical and cultural period[s].”

“Marxism was a theory developed in a particular historical epoch in the 19th century in Western Europe, but Marxism is completely useless for understanding most developing countries,” he said. “There’s no proletariat in Africa, I’ve never met a capitalist from the Congo or Sierra Leone. It’s just irrelevant.”

It’s not that only economics or anthropology has the right approach, Robinson said. No one field has found “the tools or the concepts for thinking in a genuinely comparative way about human societies.”

In the meantime, Robinson and Acemoglu will be getting out into the field in search of answers.

“Spending time in developing countries helps you see, ‘I just don’t understand this.’ We’re always learning, and we’re always reconceptualizing,” he said.