Recently, the Art Institute of Chicago made an exciting accession to its permanent collection: several works by contemporary artists Amanda Williams, Bisa Butler, and Tschabalala Self. On October 22, the museum hosted a discussion titled #BlackGirlMagic to celebrate the three artists—all women of color. At the talk, the artists shared wisdoms from their creative journeys, talked about the works acquired, and discussed the importance of challenging the systemic prejudices of the art world by championing the work of artists of color and women.

The presentation was organized by the Leadership Advisory Committee (LAC) at the Art Institute. Composed of African American community leaders, the committee is devoted to promoting racial diversity within the museum on various levels. The New Paradigms series is one such way the LAC pursues a more diverse institution and elevates the visibility of artists of color. At #BlackGirlMagic, the three artists were joined in a conversation moderated by Kyra Kyles, the Media & Storytelling program officer at the Field Foundation. The program was initiated by an expressive reading of works by Toni Morrison, read by poet Rachel “Raych” Jackson.

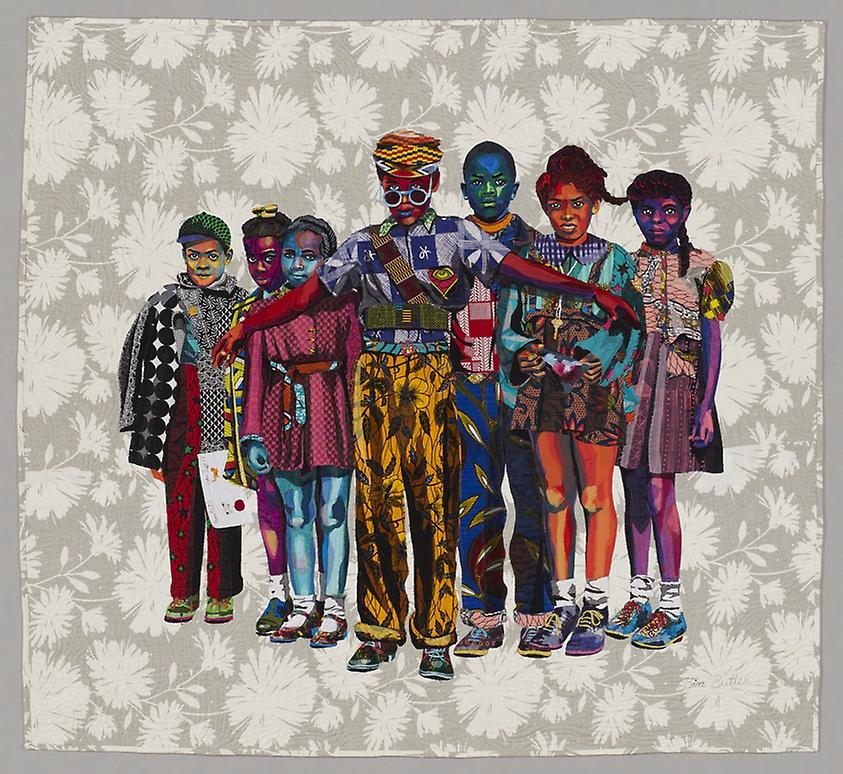

The first speaker, Bisa Butler, was formerly a Newark Public Schools art teacher, and now works as a professional artist—specifically, a quilter. Although formally trained as a painter, Butler admitted that it was not until later in life that she found her calling in the sartorial arts, looking back to her early childhood when her mother and grandmother taught her sewing techniques to create stunningly colored, textured, and detailed works in various fabrics. The artist’s research process involves deeply scouring photographic archives and pulling out forgotten or forsaken histories to reanimate with needle and thread. Set to be exhibited in a 2020 solo show of Butler’s work at the Art Institute, “The Safety Patrol” (2018) is the museum’s first acquisition of her work.

Next up, New Haven–based painter Tschabalala Self spoke about her piece, “Thank You” (2018), now part of the museum’s collection. Self’s current practice is focused on iconographies, realities, fantasies, and representations of the Black female body in contemporary culture. Often occupying emotive color fields, but sometimes situated in perennial settings, the Black figures in Self’s work exist for their own sakes rather than for another’s gaze; their presence is not performative. The artist cited Faith Ringgold as one of her inspirations, as did Butler.

Finally, visual artist and architect Amanda Williams discussed her project, “Color(ed) Theory” (2013–15), which involved painting eight abandoned houses in Chicago’s South Side various colors—each one a solid, culturally specific hue. With shades such as “Crown Royal Bag,” “Flamin’ Red Hots,” and “Pink Oil Moisturizer,” the houses were painted in colors meant to evoke Black consumer culture. The decrepit structures of the homes were converted to striking social sculptures that spoke to the city’s underinvestment in Black communities. As Williams said in a TED Talk about the project, “‘Color(ed) Theory’ catalyzed new conversations about the value of Blackness.” Photographs of said houses are now in the Art Institute’s collection.

Towards the end of the evening, moderator Kyles asked the artists what people could do to help elevate artists of color. Being present, vocally supporting their practices, and attending their events were among their recommendations. “Buy the work,” added Butler, to enthused applause. The artists all stressed the importance of acknowledging the work of Black artists in a world that constantly seeks to shut them down. In response to the event’s title, #BlackGirlMagic—a term popularized by CaShawn Thompson in 2013—Williams said, “It’s not magic…it’s work.” While by no means a be-all and end-all, the Art Institute’s recent acquisitions and programming serve as a productive step towards a more equal and just museum industry that appreciates artists’ hard work.