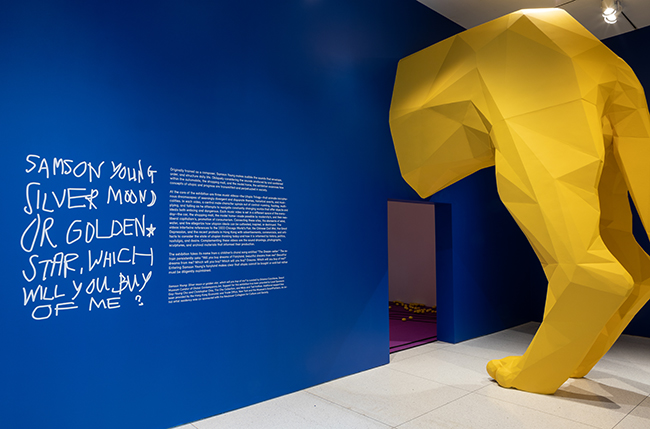

A floor-to-ceiling, geometric papier-mâché sculpture of a lion’s hind legs greets visitors as they enter into Hong Kong artist Samson Young’s first solo exhibition in America, Silver Moon or Golden Star, Which Will You Buy of Me? They wander into a room at the Smart Museum with a scattering of plastic lemons in which a lone lemon-headed robot quietly pushes away any fruit along its pre-coordinated, magnetized path.

In this exhibition curated by Orianna Cacchione, Samson Young draws upon the strange, abstract, and unrealized idealism of the 1933 World’s Fair in his criticism of the futile ambitions to achieve perfection. His music videos, sound images, and 3-D-printed sculptures warn us that a promise of progress can also be the fatal blow of regression. In particular, he pits optimism against dread, nostalgia against defeat, integration against incongruity, challenging the evergreen positivity of innovation.

The lemons and their accompanying music video, “The highway is like a lion’s mouth,” constitute the first room: the plastic fruits are tossed around in unequal clusters on the floor, the lemon-robot endlessly loops around a serpentine path, and the four connected screens on the wall display bizarre animations of human figures glitching, running, and contorting themselves on ever-spiraling roads. The open floor invites attendees to freely kick at the lemons, blocking or clearing the robot’s path. But it all comes to naught, because the robot casually sweeps the fruits out of its path, silently, obediently. This mindless act on a prescribed path appears to be a criticism of self-driving automobiles; the imperfect design of the automated lemon causes it to indiscriminately knock over the pedestrian lemons, because it can only follow a predetermined road. For all its benefits, driverless transport also poses a very real threat to us.

Using the car as a “symbol of optimism and source of anxiety,” “The highway is like a lion’s mouth” departs from cars’ typical connotation of freedom. The figures in the music video are free to run and ride cars through racetracks that speed through mainland China, then to Hong Kong. However, upon closer inspection, the racetracks appear to be an infinite loop. The “car” sign onscreen acts as a political assertion and warning from Young. As a disabled figure in a wheelchair looks on in the video, with electronic music resonating nervously in the background, Young’s political motivation becomes clear: the Chinese government uses the road as a means to control citizens of Hong Kong, telling them to stick with a “HARMONIOUS SOCIETY” but keep in mind that “YOU DON’T OWN THE ROAD.”

The subsequent hallway presents some visual material from Young’s research into the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933, conducted during his residency as a Visiting Fellow at the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society. The second-ever world’s fair held in Chicago, it was officially named “A Century of Progress,” showcasing the momentous innovations of the 20th-century and imagining what lay ahead. Emerging from the depths of the Great Depression, this world’s fair celebrated the vindication of capitalist ideals and democracy. From this century of progress, however, comes a Foucauldian sense of maintenance and control over every aspect of life. In order to maintain this booming progression, tasks must be managed to ultimate efficiency to promote ever-increasing superiority. Young demonstrates this rigid societal routine, from ridiculously meticulous instructions for Royal Desserts; to a romanticized sign of a “fit” and “superior” nuclear family, muscular father and graceful children and all; to the promotion of a healthy lifestyle that conflates eugenics with economic benefit, be it the perfect Gerber baby or the ideal house-cleaning wife. To what extent are we willing to sacrifice our humanity and individuality for the sake of a beautiful, orderly utopia? And considering that this was the expectation of the 1930s, just shy of 90 years ago, can we finally admit that this is an impossible task with which we have irrationally burdened ourselves?

The music video in the exhibition’s penultimate room is preceded by a row of 3-D-printed blocks, called “support structures.” This part of the show sends a more optimistic message about the age of progress; Young admits that he admires the funky, unorthodox printed shapes. He is particularly impressed that the structures “follow their own logic”—while the designer has control over the potential shape, the machines may churn out a slightly different structure than expected. There is a beauty to this uncertainty, a sense of eccentricity even within the math and technology. Standing adjacent to the structures is the “My car makes noises” series—documentations of car sounds that are engineered to boost a sense of exhilaration (e.g. a car’s acceleration), or to evoke anxiety (e.g. car squealing, which is, according to Young, a very linear sound-image). How can one thing be two paradoxical statements at once, Young seems to ask, and how does it both give and take power away from the human?

The third music video, “Houses of Tomorrow,” features two 1930s homes, one of them in ruins, stripped to its barest structure. In one scene, a suited singer gleefully sings Bing Crosby’s “Did You Ever See a Dream Walking?” He croons and taps excitedly on his electronic tablet, seemingly ignoring the ruined kitchen behind him, stocked with nothing but jars of Miracle Whip—cheap mayonnaise. As he vocalizes, images of protests appear on the screen. One in particular features a banner—probably belonging to Hong Kong protesters—that reads in Chinese: “IF WE BURN, YOU BURN WITH US.”

The exhibition ends with “The world falls apart into facts #2 (The Dream Seller),” in which a video of a storyteller wearing a cow mask plays on a screen, telling the story behind the Chinese proverb “A donkey’s lips do not match a horse’s mouth.” Young challenges this notion, asking us to consider what we can learn about the fact that cows, donkeys, and horses can still effectively communicate. What is the power of sound in a context of different, clashing cultures? Can wildly contrasting worlds be integrated into one?

From criticism of Chinese control over its administrative regions to the American ideals of the perfect human and family, Silver Moon or Golden Star, Which Will You Buy of Me? takes viewers through a technicolored, technologically driven journey through history. In this body of work, Young acknowledges the importance of striving for a better future, but reminds us that we must never choose to ignore our present problems in that pursuit.