Opera deals with death constantly. Whether it is Brünnhilde’s sacrifice at the end of Götterdämmerung or Cio-Cio San’s suicide in the finale of Madama Butterfly, sacrificial deaths in opera are commonplace. Dead Man Walking, which was composed at the dawn of the new millennium by Jake Heggie and commissioned by the San Francisco Opera with a libretto by Terrence McNally, is no exception. However, what differentiates this story from the sacrifices of operas past is its simple message about capital punishment: No one is beyond redemption and no one—not even the most hardened, vicious criminal—is beyond God’s help. Engaging this controversial political debate with intense focus and powerful singing, the Lyric Opera’s current production, running through the end of the month, is a must-see.

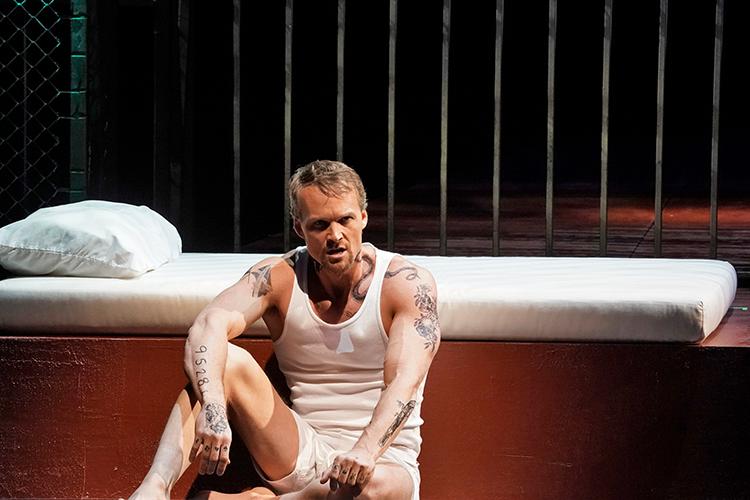

Dead Man Walking, based on a true story, tells the story of Sister Helen Prejean (Patricia Racette) a nun from Louisiana, who begins a correspondence with a convicted rapist and murderer, Joseph De Rocher. At first, swastika tattoo–bearing De Rocher seems irredeemable. In the prelude, for example, he rapes a teenage girl and then murders her and her boyfriend. Bolstering this image is bass-baritone Ryan McKinny’s performance. He does a tremendous job of showing De Rocher’s hardened, hopeless soul through his acting while his profound voice carries his lack of remorse powerfully and clearly to the very top of the house.

Sister Helen believes she can redeem Joseph before he dies. In doing so, she finds herself at odds with Mrs. De Rocher, Joseph’s mother—played by Susan Graham, who starred as Sister Helen at the opera’s premiere in San Francisco 20 years ago—and a chorus of the parents of the deceased teenagers. Since the opera is noticeably light on melody, the Lyric’s production has the opportunity to shine the most during these ensemble scenes.

Graham, suffice it to say, is magnificent, the pain and sincerity in her voice palpable from her initial appearance before the parents’ chorus. However, this emotion does not dull her sound one bit: More than any other singer, her sweet, deceptively voluminous, mezzo-soprano entranced the audience on Saturday evening. Another pleasant surprise came from the father of the murdered girl, sung by bass-baritone Wayne Tigges. His incredibly deep and crystalline voice portrayed the desperate nature of the parent of a deceased child with heartbreaking and forceful detail.

Soprano Racette’s performance as Sister Helen, on the other hand, was only all right. Her voice was excellent on its own, but her acting and timbre was noticeably stiffer than that of her predecessor in the role, which left the audience wanting slightly more. Joining Sister Helen along her journey is Sister Rose, the abbess of Sister Helen’s mission, portrayed by soprano and Ryan Opera Center alum Whitney Morrison. Sister Rose forms a terrific companion to Sister Helen, often making up for Racette’s emotional monotony in spades.

The production—a very rare instance wherein a modern set is indeed set properly in time—is well-executed. Its forest, while full of metal poles instead of trees, gets the point across quite well, and Sister Helen’s bright classroom provides much-needed relief from the dark and depressing set that is the prison. That set is depressing for a reason, since it is the place where Joseph De Rocher is eventually put to death on a terrifying machine in the final scene. This scene ends with an incomplete rendition of Sister Helen’s hymn, too suddenly for the audience to fully make sense of what has happened. Perhaps it was intentional.