It is difficult to know how one is meant to witness art that looks inward, yet this paradox has not deterred people from producing or consuming such works. In The Absence of Light: Gesture, Humor, and Resistance in the Black Aesthetic, on view at the Stony Island Arts Bank through December 29, embodies this conflict wholeheartedly. Centering around “artistic practices that…reveal some sense of interiority,” the exhibition contains several works that depict the inner lives of Black people, a focus that seems a response to the lack of nuance that normally characterizes the purely exterior perspectives on Black lives. The collection features over 20 artists from across the diaspora, highlighting the Black aesthetic across various mediums dating from the mid-’60s to 2019.

In one painting, entitled I’m not dangerous, a Black boy holds a rifle against a green background. In Unfinished Commission of the Late Baroness, the titular baroness sits on a desk, her face and hair the only portion colored in. Though the two artists, Henry Taylor and Toyin Ojih Odutola respectively, work in different cities from different backgrounds, they are placed side by side for a reason. Just as Taylor characterizes his art as “landscape paintings” to highlight the connection between his art and the world around him, Odutola explains in a recent PBS interview that making art like “a topography” or “a landscape” helped her combat portrayals of Black life from outsider points of view.

While interiority is the focus of the works presented, many also take on the concept of distance. Nate Young’s Untitled (Altar No. 12) consists of a sheet of shaded paper with a thin horizontal line ending in two arrows stretching across its middle. The paper is held within an oak and walnut cabinet, doors open to reveal a semicircle behind each door, divided in half by another line with an arrow at its far end. Interiority is literally challenged in the work, the sheet of paper contained within a structure which also serves as an extension. The piece is hung in the south gallery, alongside the experimental acrylics of Jack Whitten and Torkwase Dyson and a bombastic portrait by Robert Colescott, whose dramatic colors and silhouettes stand out against the black-and-white palette of nearby works. This tension is also a central part of the exhibit’s curation; opposite forces are constantly at play in each gallery just as they are within each work of art.

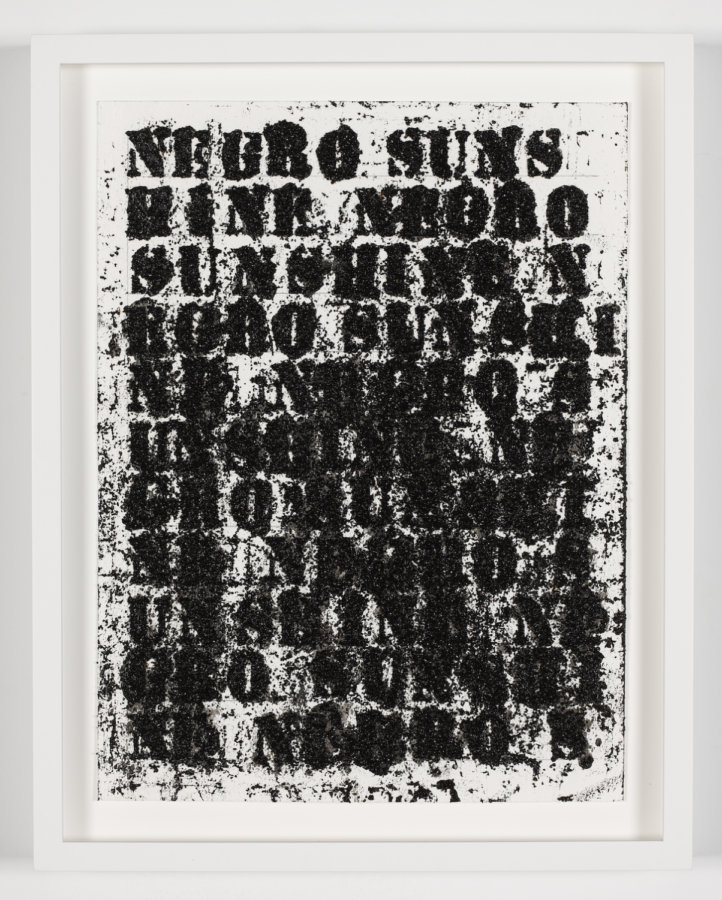

A portion of the north gallery is dedicated to Glenn Ligon, a New York–based artist whose work does not center around interiority but fully engenders the exhibition’s theme of gesture. This is most prominent in Ligon’s popular text-based art, in which he fills in stenciled excerpts from Black poets and writers with oil stick. One such piece on view at the Arts Bank is Study for “Came and Went,” which quotes Richard Pryor’s famous routine on Black funerals. The character of the work is a feature of how it was created: The smears and scratches from Ligon’s hand are clearly visible, nearly obscuring some of the letters. The messiness of the appropriated text distances it from its origin, pointing towards the way both age and transformed perspectives have shaped the words’ meaning since Pryor wrote them in 1978, 30 years before the piece’s creation.

The breadth of work, gathered through the Rebuild Foundation’s collaboration with EXPO CHICAGO, Art in America, and the Beth Rudin DeWoody Collection, offers a unique perspective on the present and past of Black art by focusing on internal, gestural works. When the lives of Black people are so often framed in terms of external conditions, to approach them from within is a refreshing, challenging perspective.

In the Absence of Light is on view at the Stony Island Arts Bank through December 29.