In Hebru Brantley’s latest artistic endeavor Nevermore Park, he transforms an old house in Pilsen into the 6,000-square-foot fantasy world of his iconic characters Flyboy and Lil Mama. Though perhaps best known for his graffiti and paintings, Brantley has experimented with film, sculpture, and many other media, before attempting a project as extensive and all-encompassing as his new interactive installation.

Before entering Nevermore Park, each visitor is given a copy of the Nevermore Herald, the main headline of which asks, “Who is the New Flyboy?” The art exhibit begins in the white walls of a typical gallery space, with portraits introducing his characters to those unfamiliar with Brantley’s work. From there, visitors are ushered through a tunnel lined with old Chicago newspapers that point to important figures and moments in the history of Black Chicago. These newspapers are just one of the ways Brantley localizes history in the exhibit. After stopping by Flyboy’s workstation, we pass through Pullman Train Station, the site of South Side industrial worker strikes and the first African-American union in the country. Posters of Sun Ra and music by Chance the Rapper tie the space to Chicago’s cultural history as well.

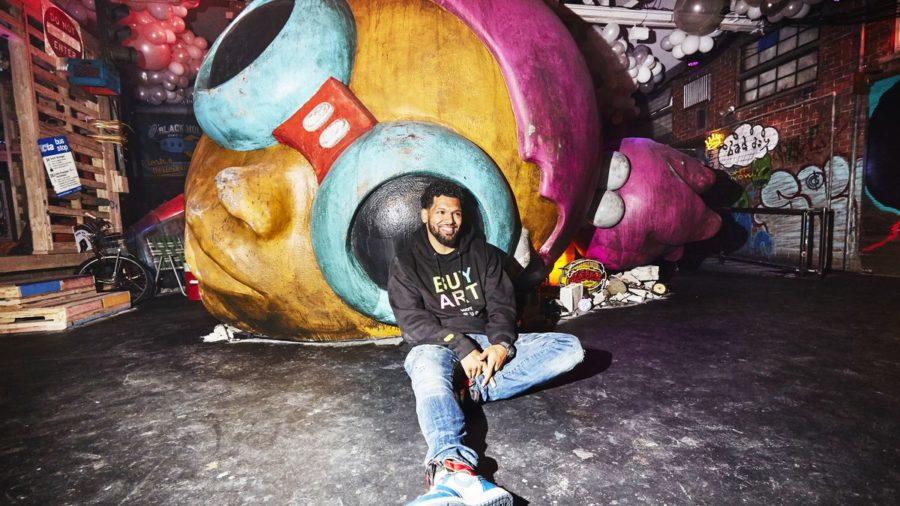

And while the exhibit feels distinctly “Chicago,” everything from the Black Hole Donuts rocket to the enormous Lil Mama head catapult us to something far more fantastical. Flyboy’s workspace, complete with his green aviator hat and yellow goggles, is filled with sketches of flying costumes. Even our sense of time is distorted as the lights cycle through a day every hour, the exhibit seeming to defy the foundations of time and space. In merging a historic Chicago with futuristic characters and technology, Brantley makes a recognizable place new. His concern with repurposing spaces implies an ever-changing, growing community defined not only by the found objects within it, but also through the visitor’s experience within its architecture.

Brantley removes the subject from the canvas, positioning us as an active character in his art. Nevermore Park asks visitors to walk through its El car, sit and read comics in its play spaces, explore its church-turned-garden. The attention to detail is incredible, each room populated with carefully-selected items by Brantley’s design team. The project was conceived over a year, with two months dedicated to the construction of the actual space. But once one is immersed in the exhibit, it feels organically made rather than strategically planned out, pointing to Brantley’s skillful balance of the familiar and unfamiliar, fictional and real elements.

One of the most interesting recurring pieces throughout the larger exhibit was the sketches of characters within it. Smaller pieces such as the drawings from Flyboy’s journal or pages hung up on the walls of the repurposed bike shop are self-referential, reminding us of the art’s indefiniteness and our place in the creation of it. Outside the bike shop is a chalkboard with Brantley’s flying characters, where visitors are more directly asked to contribute to the exhibit through adding color, dialogue, and personality to the characters. How should we imagine these characters to be like? One answer is found within a speech bubble: “I want to eat sour patch kids.” And who is the new Flyboy? As the exhibit divorces itself from a clear narrative, it prompts us to create our own. Brantley writes in his blurb on the gallery wall, “While viewing the paintings that once revealed the narrative of Flyboy we now sit within the painting.” Through participating in the art, Flyboy’s narrative becomes our own, or ours becomes part of his. The visitor is simultaneously character and artist, projecting their home onto the one Brantley has made, able to look and find themselves in the items or words or music of the piece.