When Nazi Germany forced the Bauhaus school of design in Weimar, Germany to permanently close its doors in 1933, many of its members felt that their revolutionary work in design was unfinished. Resolved to continue the work begun by the Bauhaus and its famed professors, such as Wassily Kandinsky and Walter Gropius, a group of instructors took root in the United States, taking particular interest in Chicago and the American Midwest. Among these transplants were Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and László Moholy-Nagy, who were both invited to teach at the New Bauhaus, now the Institute of Design (ID) at the Illinois Institute of Technology (ITT). Beginning in the mid-1930s, Moholy-Nagy and Mies created a modernist legacy in architecture and the arts with the help of their pupils and contemporaries. Their influence is still deeply felt in Chicago to this day.

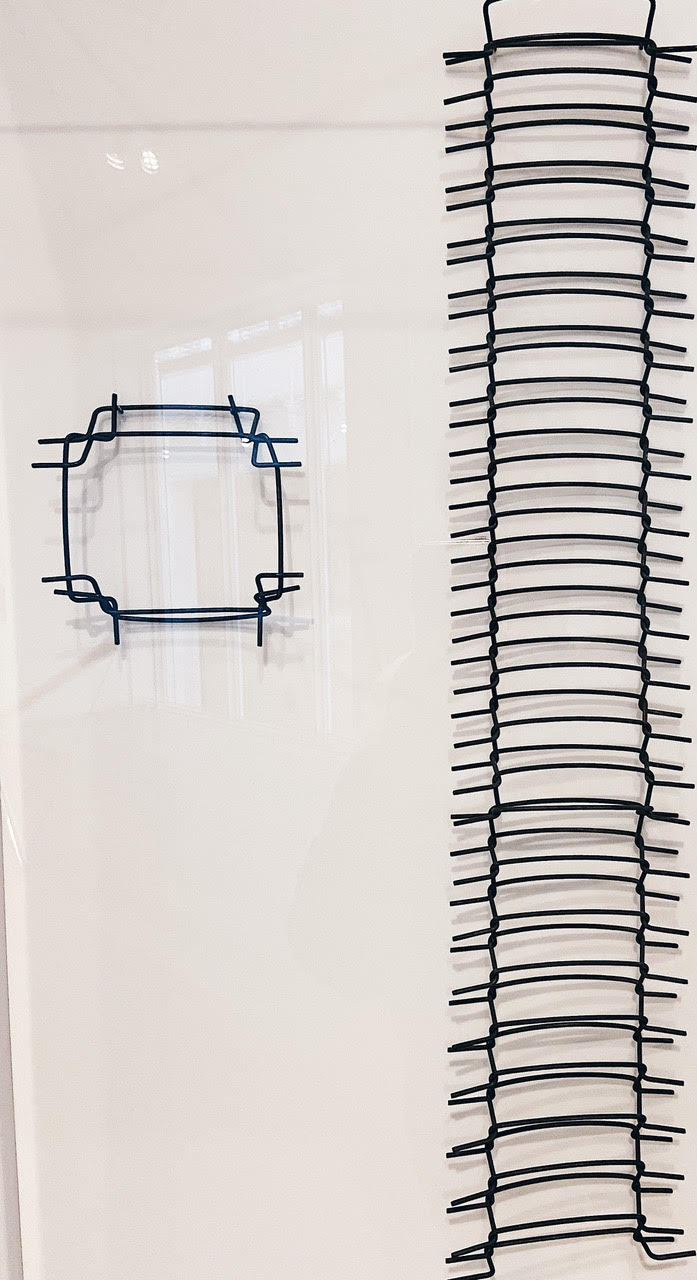

Because the media has extensively covered superstar figures such as Moholy-Nagy and Mies, it is quite refreshing to see an exhibition focused largely on the works of their previously anonymous students, emerging a century after the founding of the original Bauhaus. Importantly, many of the lessons taught at both the original Bauhaus and its American schools dealt with the qualities and characteristics of individual materials, favoring intimate interaction with objects and great design over formal artistic or architectural training. As such, many of the pieces on display in the small but densely populated space at the Art Institute are vaguely architectural but maintain a deeper focus on the simple form and materiality of everyday objects within the industrial context of the 20th century. This philosophy is readily apparent in works such as Institute of Design Foundation Course Wire Exercise, in which a delicate wire-framed sculpture vaguely references industrial hallmarks, like skyscrapers and metalworking. Similarly, Hall of Sport and Culture, Collage, dated from the early 1970s, features a football player, a pair of dancers, and a crowd set within the context of what appears to be a sort of building, itself resting on color blocks. In fact, the work was equally inspired by a building in Detroit as it was by modern art, film, and the emerging technique of collage.

The exhibit also seeks to correct for the historical lack of recognition of the many women who studied in the Chicago Bauhaus schools. One such figure who is featured prominently is Dori Altschuler, whose work during her time at the ID recently received recognition from several national publications, as well as from the journal Arts & Architecture in 1952. Altschuler’s use of recycled shopping bag materials to make architectural sculptures is particularly interesting within the contemporary context of natural resource conservation, as it seems that she—and the Bauhaus movement in general—was well ahead of her contemporaries in understanding the existential threat that urbanism and modernization posed on the planet’s natural resources.

Despite their innumerable contributions to design, architecture, and art, the Bauhaus’s insistence on unified, homogenous urban spaces master-planned by privileged Europeans and Americans allowed for the creation of troubling projects, notably on Chicago’s South Side. Enacting a plan that eerily recalls Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s classist transformation of Paris during the 19th century, Mies and IIT demolished large tracts of land on the South Side, displacing large populations of low-income Black families and businesses under the guise of “urban renewal.” The effects of this process are still glaringly obvious today, when the de facto segregation of wealthy, white Chicagoans and low-income Black Chicagoans remains an unsolved issue. Standing almost as an allegorical testament to this shameful period, Mies van der Rohe’s School of Social Service Administration, completed in 1965 for the University of Chicago, sits prominently along 60th Street, which has long represented the border between the vast property of the University and its wealthy inhabitants, and the Woodlawn community occupied primarily by low-income residents of color.

Viewing the contributions and controversies of the Chicago Bauhaus era in equal proportion, Bauhaus in Chicago: Design in the City presents perhaps the most comprehensive and most progressive retrospective on the movement. On view through April 26, 2020 in Gallery 283 of the modern wing, this show is not one to miss.