The following review contains spoilers.

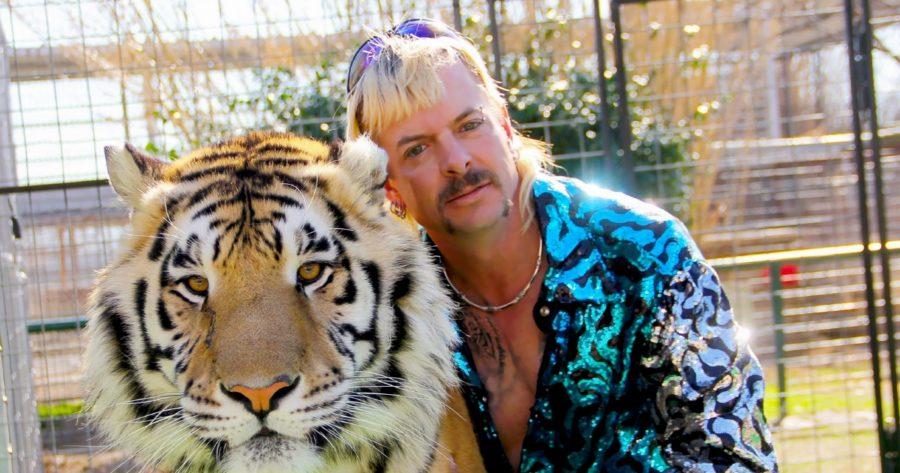

Three days into my two-week quarantine back home in Singapore, I finally succumbed to watching Netflix’s Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness because the rest of the world had already done so. This is a true-crime documentary that would otherwise have escaped my radar, yet after a seven-hour binge I found myself embroiled in deep, bizarrely passionate arguments about the show with my friends. It seems radically improbable that I would find myself so invested in a show about a tiger park in Oklahoma, but then again Tiger King is a radically improbable show. You couldn’t write its plot even if you really tried—a gay, polygamous, sequined big cat park owner in Oklahoma is accused of plotting the murder of an animal rights activist. Not one of the main characters is remotely likable, or good by any stretch of the imagination—not the eccentric protagonist Joseph “Joe Exotic” Maldonado-Passage (’80’s mullet and all), not the leopard-print donning animal rights activist Carole Baskin, not the comically villainous millionaire investor Jeff Lowe. Every turn in the show teems with blackmail and skullduggery of the highest order, yet I couldn’t begin to care about the ethics of it all.

I am not alone. There is something to be said about how we are drawn to watching horrible people on television. Recently, Netflix has been trying to corner this market and has turned in quite a pretty dollar—earlier this year, the hit reality TV show Love Is Blind was replete with characters who were deeply manipulative and emotionally abusive. In 2018, Wild Wild Country captivated the country with its depiction of the Rajneeshpuram cult in Oregon. And who can forget the numerous thirst posts for an actual convicted serial killer, after The Ted Bundy Tapes came out early last year?

Even by these lofty standards, Tiger King eclipses anything and everything that precedes it in terms of cultural impact and the comic banality of its horribleness. There is no time for the camera to zero in on one thing—it jumps and supercuts from abusive, drug-addled relationships, to questions of underpaid and highly dangerous labor, an actual sex cult, a suspected murder for inheritance money…the list goes on, never lingering too long on any moral quandary. No matter what directors Eric Goode and Rebecca Chaiklin assert about taking an objective deep-dive into the big cat trade in America, we are presented instead with evil as commercialized spectacle. And it’s worked—there are reports that Kate McKinnon will star in a dramatized remake of the show, and quarantined Hollywood actors have been clamoring on the Twitterverse to be cast as Joe Exotic.

I truly struggle to find one single compelling reason for the show’s present status as a cultural phenomenon. Perhaps there is something timely about watching Tiger King in 2020—something quite supersized and all-American in the ridiculousness that pervades the show. Is it really improbable, for instance, that Joe Exotic runs for political office halfway into the series? After all, he wouldn’t be the first reality TV star to assume public office. One of my favorite moments in the whole show comes at the gift shop of the big cat park, where Joe continually replays a three-second segment of his campaign video, in which he sits resplendent on a throne with a tiger at his feet. At once a cult hero and a man reduced to pathetic self-worship, Joe’s moments of self-absorption and megalomania are comprehensible and even sympathetic when contextualized against the current president of the United States.

However, the true allure of Tiger King is rooted in its amnesiac, conservative escapism. In a time where our received understandings of health care and the economy are failing us dramatically, the show kids us to believe that we don’t have it quite as bad as what went down in Oklahoma over all these tigers. There is almost something shamefully seductive about the way Goode and Chaiklin angle their camera with disdain toward the stereotypical redneck proudly embodied by Joe Exotic. The opioid epidemic, the question of post-parole reintegration, the intersections between LGBTQ+ identity and mental health in rural America—all are very real issues experienced by very real people on the show, yet Tiger King merely uses these issues as backdrop for the manufactured drama the producers capitalize on. In this universe, the redneck gay husband with the “meth teeth” is the punchline, not the problem. We are drawn to horrible people on screen because they are portrayed as too bad to be true, as caricatures too wildly improbable to be coterminous in our own horrible reality.

Does that make us complicit as unethical consumers? That’s a hard question to answer fully—there is definitely value in escapism in these troubled times, after all. Better to think about the tiger men than the steeply rising rates of infection. Either way, however, the show’s attempt at presenting a detached reality separate from ours is highly tenuous. How do we make sense, for instance, of the fact that Joe Exotic is reportedly in quarantine because of the coronavirus? Or that, in the middle of a press conference held largely about the management of the virus, a reporter asked President Donald Trump whether he would consider giving Joe Exotic a presidential pardon? Indeed, when reality meshes into hyperreality, the biggest losers are the tigers themselves—like its characters, the narrative, so flimsily bookended at the start and the end of the series by insipid appeals to animal conservation, loses sight of it altogether. It takes the imprisonment of Joe Exotic for the viewer to realize that the tigers have been imprisoned throughout the series. Perhaps that is the biggest tragedy of the show.