The University of Chicago Medical Center (UCMC) recently launched a clinical trial to study whether plasma from recovered COVID-19 donors can be used to treat patients with the same disease. No preliminary results have been released yet.

The study, which began on Monday, April 13, looks to utilize convalescent plasma therapy to combat the virus. Convalescent plasma therapy is the process of taking plasma, the liquid part of blood, from individuals who have recovered from the disease, and giving it to patients who currently have it, in order to transfuse antivirus antibodies.

“Your body, when it sees a virus, it recognizes the proteins of the virus,” Maria Lucia Madariaga, a thoracic and lung transplant surgeon at the UCMC leading the study, said. “There are several different mechanisms for the way it fights off the virus. One of them is to create antibodies which are specific to the virus protein, that then signals to the immune system to kill off this virus. And so, by giving those antibodies to people who are suffering from the disease, it can serve to treat people with the disease and help them better.”

This is not a new process. Initially, convalescent plasma was designed as a prophylaxis, an action taken to prevent a disease. For example, in the 1900s, children were given convalescent plasma from others who had recovered from measles, and it served as a makeshift vaccine to protect against measles infection.

More recently, convalescent plasma has been used as a therapeutic to treat cases such as influenza, MERS, or SARS infections. In other words, it has been used to help make people feel better and recover from illness, as opposed to being used with the aim of preventing infection.

For this study, the UCMC is recruiting 100 people to donate their plasma. They must meet the screening criteria: be 18-years-old or older, had a positive COVID-19 test in the past, be eligible to donate blood, and currently have no symptoms.

However, because they are still trying to assess the feasibility and safety of the project, the team will start by treating 10 patients who are currently at the UCMC.

The trial will be conducted in collaboration with UCMC immunologist Patrick Wilson, whose lab studies antibody immunology. Antibodies are protective proteins produced by our immune systems in response to the presence of foreign substances, such as viruses and bacteria. After recognizing these foreign substances, antibodies latch onto them and help facilitate their removal from the body. This means that as patients are treated in the clinical study, if an effective antibody is discovered, Wilson’s lab could try to use this antibody to develop new medications and possibly a vaccine.

“What we will be able to do in our study, is hopefully we can say that ‘this plasma that we used on this patient, it helped them a lot.’ Or, ‘this plasma that we use on this patient, it didn’t help them a lot,” Madariaga said. “Then we can take the plasma that helped a lot, and say, ‘okay, what in this plasma works well, what was able to fight the virus?’ So we can figure out what targets do those antibodies use against the virus.”

Wilson’s role will be to find monoclonal antibodies from that information. Monoclonal antibodies only bind to one specific substance, so they “can be used as drug therapy,” Madariaga said.

The study will be conducted in partnership with a wide range of facilities and personnel at the UCMC—the blood bank, Department of Medicine, Department of Surgery, transplant team, and others.

“This study takes a donation from a plasma donor all the way to a patient in the hospital who is sick, so it touches a lot of people along the way,” Madariaga said. “It brings all these people together in order to make something happen…. The fact that University of Chicago has all of these players under one roof is really unique. A lot of studies going on right now nationally don’t have their own blood bank, don’t have their own scientists…. We’re lucky that we have everything here.”

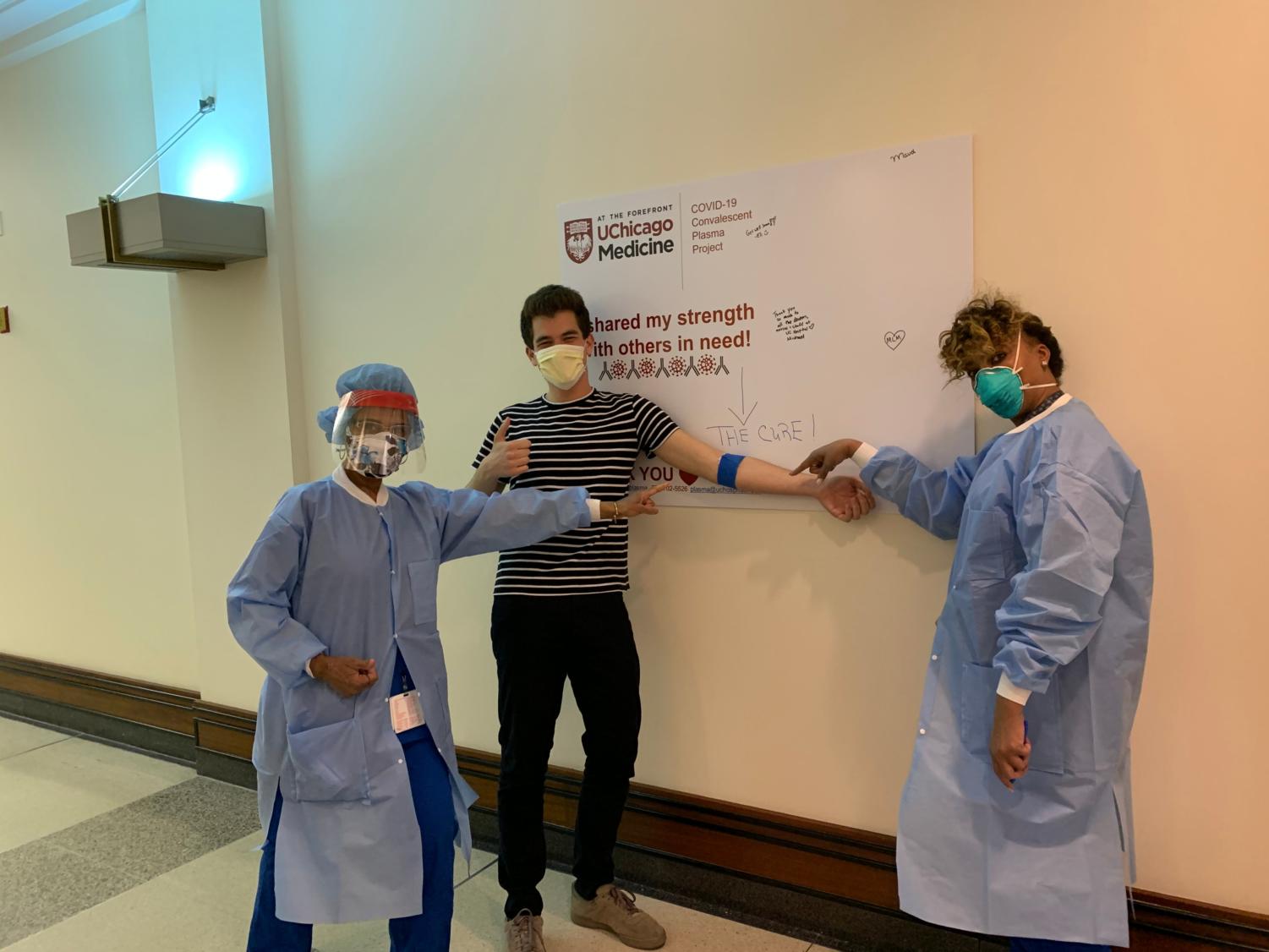

One of the donors, Michael Rubin, is an alumnus of the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools and a current second-year at Columbia University.

“I first filled out a survey online detailing when I got my diagnosis, what my symptoms were, how long they lasted, and that kind of stuff,” Rubin said of the process. “Within an hour, the leading doctor of the trial, Dr. Madariaga, reached out to me. While we were on the phone, she signed me up for an appointment at the blood bank. I went to the hospital and they asked me the basic questions for donating blood. And then they took my blood, and that was it.”

Rubin was sick with COVID-19 in early March, but said he recovered in four to five days.

“I was really lucky to have had a mild case, been young and healthy, and able to recover really quickly. But, there are a lot of people out there who are not having that same experience—people who are being put on ventilators, being put on ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation],” Rubin said. “And so, it was a pretty easy choice for me to make [to join the trial] that could potentially be lifesaving to a few other people. The pros definitely outweighed the cons.”

“We want to get the plasma into patients, and hopefully, we see a good response,” Madariaga said. “Once we see that we can do it, and that it’s safe and we can help people, then we can think about treating more people, helping throughout the whole city, area of Chicago.”