The carceral state isn’t color-blind, and neither is COVID-19. Since the pandemic broke out earlier this year, it has taken a disproportionate toll on people of color, reflecting glaring racial disparities in public health in the United States.

Prisons, with their overcrowding and unsanitary conditions, have exacerbated the spread of the virus as COVID-19 hotspots. Because of this, mass incarceration has severely endangered the lives of those in prison, who—given the inequality in the criminal justice system—are predominantly people of color. Given the extent to which prisons have contributed to the coronavirus pandemic and compounded the existing racial inequalities in the criminal justice system, the pandemic has made one thing clear: Tackling coronavirus will require us to radically rethink our systems of justice.

The racial health disparities associated with COVID-19 are undeniable. African Americans both contract the disease at higher rates than their white counterparts and die from it at over 2.5 times the rate of whites, according to data from the COVID Tracking Project. Indeed, despite comprising only 13.4 percent of the US population, Blacks account for 23 percent of COVID-19 victims where race is known. COVID-19 has disproportionately affected Latino communities as well: In Iowa, for instance, Latinos are only 6 percent of the population but account for over a fifth of the state’s coronavirus cases.

And it’s not biology that discriminates. The virus has not simply chosen to undertake a vehement rampage against Black and brown communities. It’s humans—and the systems we’ve built—that discriminate. Health disparities reflect that. To naturalize the racial health disparities of COVID-19 as nothing more than an immutable biological reality is to deny the effect of racism on health outcomes.

Nowhere is the disproportionate toll of COVID-19 on people of color more evident than in American prisons, which have become hotbeds for the virus. Given that Blacks are incarcerated at over five times the rate of whites in the United States, COVID-19’s toll on incarcerated populations means that African Americans are severely affected. While prisons across the country have become coronavirus hotspots, Chicago’s Cook County Jail has been hit particularly hard. By over-incarcerating to such an extent and maintaining overcrowded, unsanitary conditions, the jail has enabled the rapid spread of the virus, making Cook County Jail the nation’s largest source of COVID-19 as of April. And according to research conducted by Eric Reinhart of the UChicago Pritzker School of Medicine, just cycling through Cook County Jail is associated with 15.9 percent of COVID-19 cases in Chicago and 15.7 percent of cases throughout Illinois.

As the situation in Cook County shows, COVID-19 and mass incarceration are inextricably connected. Both perpetuate racial disparity and have combined during the pandemic to wreak deadly havoc as the virus sweeps through American prisons. Indeed, we are fighting two pandemics, one coronavirus, the other the racism that undermines the integrity of criminal “justice” systems worldwide. Unless we recognize this connection and begin to interrogate the systems that allow for rampant racism to persist, we won’t solve either pandemic.

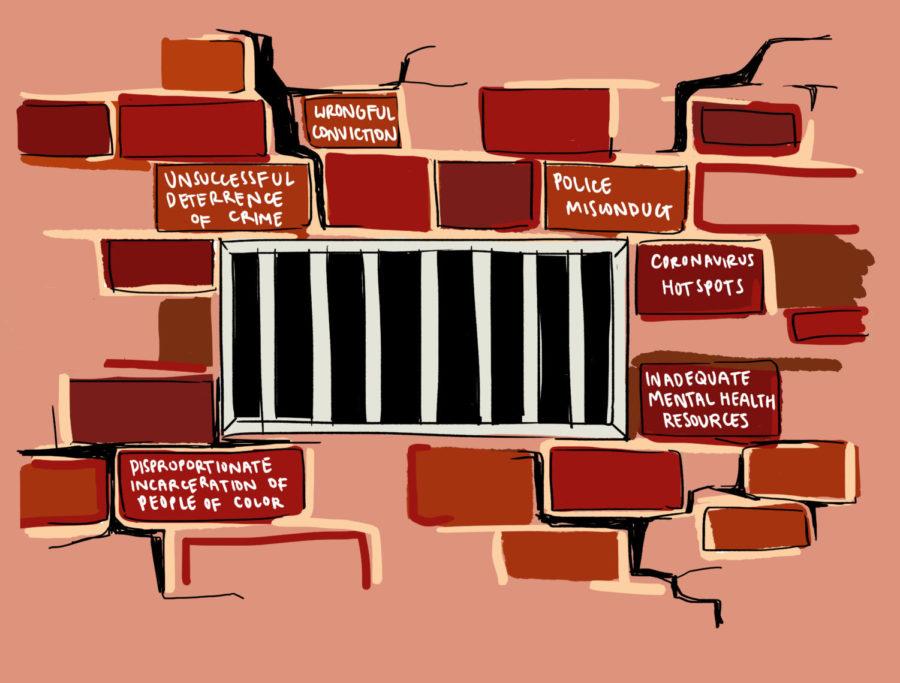

Importantly, COVID-19 has exposed the fractures in the American prison system, revealing it as a racist institution that compromises public health. It has reminded us that we cannot continue to attempt to build “better” prisons—doing so won’t address the police misconduct, wrongful conviction, racist attitudes, and plethora of other factors that cause African Americans to be disproportionately incarcerated in the first place, and moreover, won’t address the fact that prisons aren’t working to effectively deter crime. Indeed, recidivism rates show that nearly one-fourth of those released from prison return for a new crime within three years of release, demonstrating the failure of prisons to successfully deter crime. Importantly, prisons also fail to provide access to adequate mental health resources, which is particularly problematic given that incarceration exacerbates mental health whereas investing in mental health resources can actually reduce crime.

Political activist Angela Davis reminds us why attempting to reform prisons instead of reimagining justice entirely won’t work. In her book Are Prisons Obsolete? she writes, “Frameworks that rely exclusively on reforms help to produce the stultifying idea that nothing lies beyond the prison,” limiting our ability to reimagine justice and focus on decarceration. Moreover, prison abolitionist Ruth Gilmore reminds us that in a world with different attitudes towards punishment, we’ll actually see less crime: In Spain for instance, which takes a less punitive approach towards violence offenses—the average time a person spends in jail for murder in Spain is seven years—murder is actually less common.

COVID-19’s disproportionate toll on incarcerated populations throughout the United States has made it clear that in order to combat both coronavirus and racism in this country, we need to reimagine justice and rethink systems of punishment entirely. And I’m not just talking about the tearing down of prison walls. As Georgetown law professor and political theorist Allegra McLeod explains, abolition is less about the physical tearing down of prisons and more about abolishing both the culture of racialized punishment in the United States and the conditions that caused the carceral state to come about. The recent deluge of Instagram activism—both in response to COVID-19 and to the death of George Floyd—is inspiring. However, being liberal is not enough. We cannot use our progressivism as political armor or as an excuse for complacency. It’s time we realized that to fight COVID-19 we need to dismantle the carceral state.

Meera Santhanam is a fourth-year in the College and a Viewpoints editor.