2020, despite its travesties, won in the gaming world. When Animal Crossing: New Horizons dropped earlier this year, Nintendo Switch consoles sold out everywhere in America. The Honeybee Inn dance in Final Fantasy VII: Remake went viral as we re-fell in love with Cloud Strife’s narrative. One of 2020’s most anticipated releases, The Last of Us Part II, infuriated some lifelong fans with its vengeance-denying resolution and inspired others with a lesson about the futility of violence. Now, indie game Among Us has entered the chat, bringing gamers from around the world together in chaotic gameplay as impostors kill innocent crew members while denying their murderous intent.

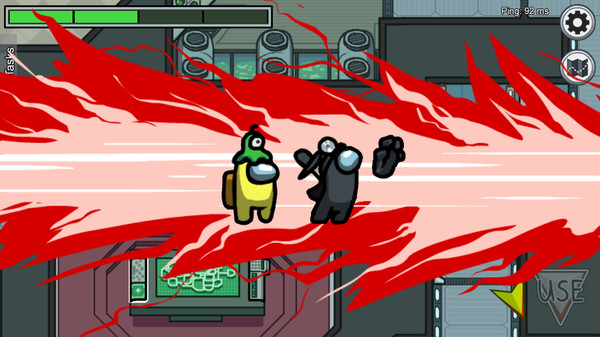

Straight out of a science fiction movie, Among Us’s gameplay is violent, yet simple: five to ten crew members are trapped on a spacecraft, fighting to keep the vehicle up and running by completing minigame tasks with a very limited visual scope. One to three impostors sabotage the crew by tinkering with the spacecraft’s mechanisms and, occasionally, murder an innocent crew member or two. The minigame tasks are unique to each of the game’s three maps: The Skeld, Polus, and Mira HQ. When a player discovers a dead body (a halved avatar with flesh and bone exposed), they report the death, calling a meeting in which all remaining players discuss who the impostors might be. Often, they compare alibis: “I was scanning in Medbay”; “I was taking forever to calibrate in the electrical room”; “You think my ass can fit in the vent?” In other, more intense discussions, accusations come flying: “I saw fake tasks!”; “Guys, if I’m wrong about them, vote me out next”; “But I saw them kill.” Breaching anarchic destruction, the gameplay frequently dissolves into furiously-typed deductions and empty promises to partner up to ensure temporary survival. After discussion, players vote out one player at a time (or skip, sparing all from death), and discover if they killed a fellow crew member or succeeded in finding the impostor. The game ends when there is an equal number of impostors and crew members (resulting in the impostors’ victory), all the impostors are discovered, or all tasks are completed.

Panic ensues with the game’s additional mechanics: the impostor can sneak into the air vents to teleport between rooms and assassinate a player. Everyone aboard can access the security cameras to spy on other players. An emergency meeting can be called, should someone see a suspicious action from one avatar…or if the impostor wishes to throw suspicion elsewhere. In sum, Among Us is a game of manipulation, deceit, and paranoia. You lie to your friends about your whereabouts, desperately coerce people into believing your task list, or descend into feigned madness as the impostors falsely accuse your innocent avatar of murder. It is best played with friends who believe your real, out-of-game life aspirations, thus allowing you to either exploit their trust or, at the very least, startle them with your brutal ability to cleave a body in half and deny the blood on your hands.

The timing of Among Us’s popularity is no coincidence: developed by a three-person team at InnerSloth in 2018, the game caught the attention of zero gamers until Twitch streamer “sodapoppin" displayed it earlier this summer. Now with over 86 million downloads, the violent nature of the gameplay appeals to the cynicism and impatience of the frustrated and socially distanced in quarantine. At its release, Animal Crossing: New Horizons offered an opportunity to build an eternally peaceful world that transcends the death and violence ravaging our own reality. It was solace in the face of pestilence. On the contrary, Among Us’s Impostor character grounds us in our lived chaos, embodying the backstabbing tendencies of real-world political leaders who swear they are working hard to keep all of us alive while reaping personal reward at the expense of countless dead innocents. Meanwhile, the crew members live with the ironic belief that they have authority over the spacecraft, which is throttling toward an unknown location and on the brink of breakdown. After all, it is within their abilities, and only their own abilities, to fix the wires, dump the trash, and fill up the fuel tanks to sustain the condition of the spacecraft. It is a beautiful, optimistic illusion: as long as the majority of us work together to save our habitat in time, the Impostor can’t stop us.

However, power actually rests with the impostors, who keep the crew members wary of each vent, sabotage, and ultimately, avatar. The Impostor figure controls the failing state of the ship—and hence the crew members—who must desperately run to every leaking oxygen tank or reactor on the brink of meltdown or face total death. The crew members live in fear and anticipation of the Impostor’s next move, awaiting the inevitable death of the next avatar or praying their democratic, yet blind, vote brings justice to the murdered. Each crew member, besides temporary alliances, feels ill-equipped and isolated: the only person they can trust is their own self. And the Impostor relishes in an unspoken power they possess: the scary ability to turn the crew members against each other, despite their collective innocence in the face of mismanaged power.

Among Us is a game I log on to after burning my eyes out in back-to-back Zoom meetings, which I suppose is the greatest ironic parallel of all: my avatar in Among Us is merely fixing wires and buying beverages as the world burns around her. I’m a student studying undergraduate-level politics as the presidential election threatens to shake the very infrastructure of the nation I’ve always known. Eerily, the narrative of the game reflects the bleakness of our own political reality—and whether we’re aware of it or not, as the crew members, we project the frustrations that the pandemic has encouraged and inflated upon the general public. We facepalm in frustration when the Impostor wins because the guilty has emerged victorious from an unjust bloodbath, and our blame-shifting has brought our demise. We find catharsis when the crew members win not simply because of a game well-played, but because Among Us has created an imaginary scenario in which we serve justice regardless of a flawed system that has kept a majority of us unaware of the violence committed. Additionally, when we are impostors, we come to realize how easy it is to cheat the system and place blame on an unaware player. All it takes is manipulative persuasion, scapegoating and, above all, extra added powers not bestowed upon the common crew member.

The objective of the game is an exhausting, disintegrating environment rigged against the crew members. Perhaps the most infuriating part comes not as a crew member, but as a murdered ghost, flying around the spacecraft to complete your tasks. You watch crew members discuss at the meeting table, unable to scream at them who the true impostors are, as they vote out another innocent player. The tension this deception capitalizes on reaches its most infuriating, posthumous peak when Armageddon ultimately crashes: the penultimate crew member is thrown out of the airlock, leaving the impostors victorious. Death is no release from the chaos of the spacecraft: in fact, it is another kind of isolation that forces you to watch faith between your crew members disintegrate. It’s torturous, and for lack of a better phrase, a metaphor for 2020 at best.

This isn’t to suck the fun out of Among Us—I’ve pulled all-nighters playing this for a reason. Seeing the self-destructive capabilities of the crew members is highly entertaining, and every wrong vote is a giddy guarantee that the impostor lives to see another murder spree. The best games I’ve played are a showdown between the last three avatars standing, a gamble of paranoid guessing with a sliver of hope that crew members might win, an exhilarating climax I, and many others, chase every game. With a fantastic player in the impostor role, we can recreate a fun, chaotic gameplay of bad faith actors, trolls, and a community of casual gamers. After the game ends, regardless of outcome, we return to the lobby to congratulate a successful impostor, share each other’s socials, and join Discord calls to babble about how stupid our logic was when Red was “lowkey sus” but no one acted on it. Among Us capitalizes on tension and disaster but offers a time to unravel with newfound peers. Sure, I might be salty at my friend who voted incorrectly when we depended on her, but the bitterness dissolves instantly after a “gg.” That’s the final framework that appeals to Among Us gamers: yes, the avatars exist within an Armageddon-like nightmare, but at the end of the day, we find ourselves coming back to this game because it’s like we’re at home, catching up with old friends when the world has returned to its normal state.

Among Us developers promised updates to the game: friends lists, a new map, more colors. I’m excited to say that I will eagerly await these updates. Until then, I will be fucking up my “Swipe Admin Card” task in The Skeld to the annoying, diegetic beeps. 9/10, InnerSloth.

Among Us is available for purchase on Steam ($4.99), and free in the App Store and Google Play for mobile. I encourage you to actually legally purchase or download this game: support indie gaming companies.