The titular subject of Dick Johnson is Dead, a new Netflix documentary, is very much alive. Dick Johnson is not dead. Yet. An octogenarian in the early stages of dementia, Dick Johnson is dying. So his daughter and prominent documentarian Kirsten Johnson uses the camera to blur lines between reality and unreality, life and loss, mortality and immortality.

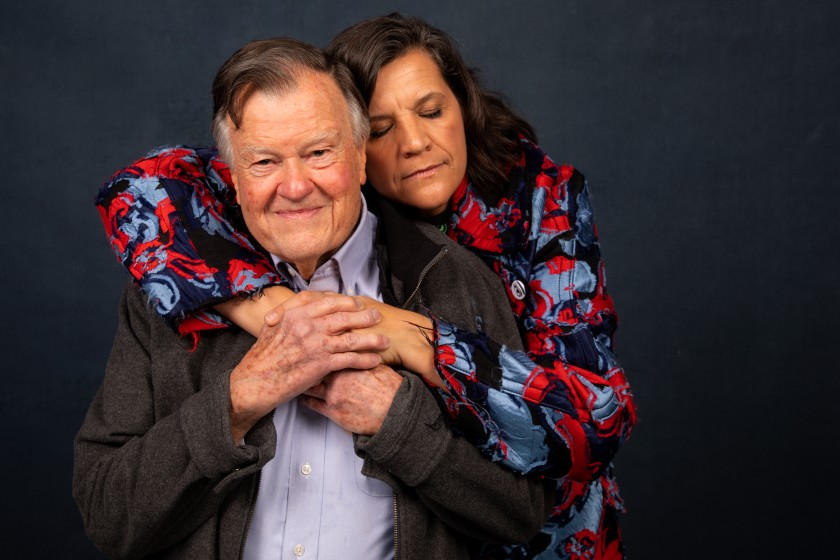

The film moves beyond the scope of record and preservation, the typical aims of documentary film, to achieve a sort of cinematic transcendence. Deeply personal and deeply felt, it follows the relationship between Kirsten and Dick as his memory begins to falter and he moves cross-country from Seattle to live with Kirsten in New York City. Unsurprisingly touching, Kirsten combines a deft cinematic touch with subversively humorous and daring conceits.

The film opens on a scene of Dick playing with his grandchildren in a barn while Kirsten tells us in a voiceover, “I suggested we make a movie about him dying; he said yes.” Kirsten means this literally. As a running gag, she stages increasingly absurd versions of his (fictionalized) death. First, he is taken out by a falling air conditioner; later, he meets his demise thanks to an errant construction worker; and so on. She has her father climb into a coffin and play dead under the glare of a camera crew and his friends. He ascends to a vibrant Heaven, one with plenty of his beloved triple fudge chocolate cake. None of it is real; all of it will eventually be.

The camera is not intended to mark any notion of objectivity. Kirsten is not purely interested in the process of aging and death, but rather in the discovery of an extended life. The camera lens transforms into her own gaze. With intimate close-ups and warm shots of Dick’s life in all of its minutiae and grandiosity, Kirsten conveys her father with loving tenderness and a genuine warmth that travels throughout Dick’s circle and quickly to the audience itself. We meet Dick. We bear witness to his passions, his confusion, his humor, his faith rooted in the Seventh-day Adventist Church, his heartbreaks, his doctor’s appointments, his lucidity, his demise, and his ascension—by the end of the film’s 90 minute run, we forget to care about discerning between fiction and reality.

Despite the joyous and sublime celebration of her father’s life, Kirsten’s film is underlain with a sense of regret. Her mother’s story is reduced to snippets: old photographs, uncovered artifacts, just tidbits from her and her father’s memories. Kirsten reveals the lone bit of film footage she has of her mother, a few minutes of the late stages of her battle with Alzheimer's. The filmmaker seems intent on ensuring that neither Kirsten’s father nor her relationship with him is consigned to a similarly undocumented state. The regret shades the joy on-screen with a certain nuance that might otherwise be lacking and reminds us that while Dick Johnson may not be quite as flawless as portrayed, Kirsten’s memories will inevitably render him so.

The great triumph of this film is that it depicts the story of one father and daughter with startling clarity and specificity yet achieves a universality so often sought after and so rarely found. A particularly wrenching moment occurs when Kirsten informs her father that she has sold his car. His eyes fill with tears, and he is stunned into silence at the loss of the fundamental independence of driving. In this moment, we are reminded of our own painful experiences with aging loved ones. We have all had or will have to watch some central piece of our loved ones’ identity be stripped away. Or gratefully, regretfully, find ourselves exempted from the task.

The candid conversations about death and gruesome stagings of Dick’s death serve a self-therapeutic purpose for Kirsten and, by extension, the audience. Dick Johnson becomes more than just himself; he becomes all of our fathers, or mothers, or friends. Kirsten, along with the rest of us, believes that we can fortify ourselves by confronting someone’s death while they’re still alive, still there to comfort us. Perhaps the self-preparation will help. Or perhaps it will not, as a pivotal late scene certainly requires some tissues.

Dick Johnson is Dead breaks all the rules of documentaries and of the cinematic experience. A film this powerful is not supposed to be this entertaining. A documentary about death is not intended to be both hilarious and haunting. A movie with such emotional immediacy should not also be timeless. And yet, Kirsten along with the ever-obliging Dick pulled off the remarkable.

Dick Johnson is alive. Dick Johnson is dead. Dick Johnson is dying. Dick Johnson will live forever. Somehow, Kirsten Johnson convinces us that all of these statements can be—and are—true.