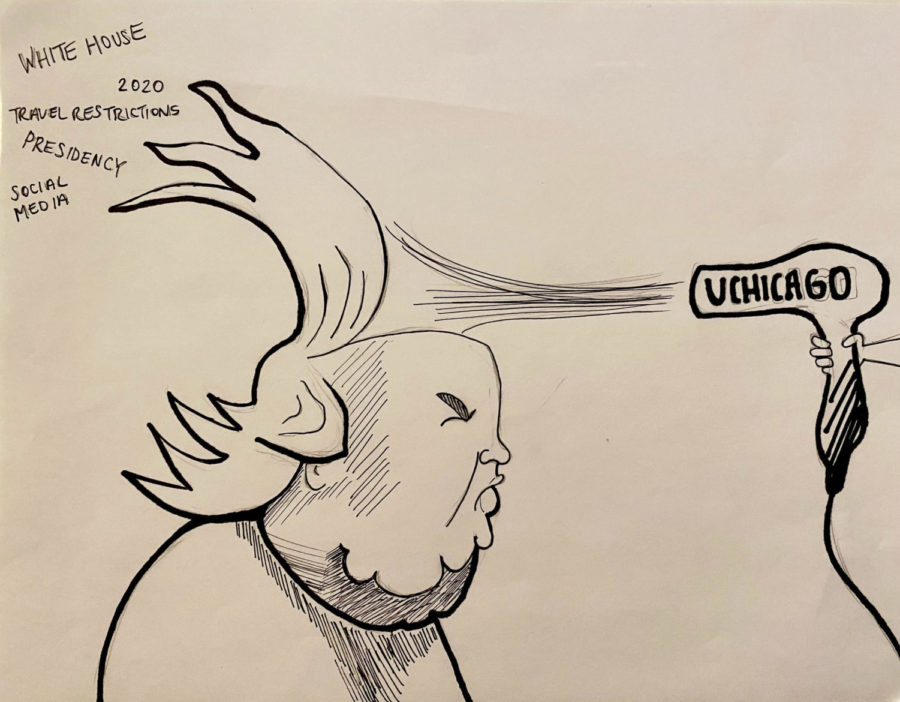

At long last, we’ve made it. Trump is out and the Biden administration is in. For many, this is a time to breathe. For the country, it is an opportunity to hold wrongdoers from the past administration accountable for the past while also looking forward to the nation’s future. The new White House is pushing hard to make sure that the previous one is limited as much as possible to the history books. For many, this return to normalcy is a welcome break from the past four years. Still, it can be a dangerous instinct to embrace. For UChicago, in particular, the urge to go back to the old days is one it should work hard to stave off. The egregious malfeasance of the Trump presidency forced our historically neutral university out of its self-imposed neutrality and into the political arena. This new, politically engaged UChicago ought not to shrink back into political silence. The University must continue advocating for just policy, even beyond the Trump era.

For UChicago, the principle of disengagement runs deep. As early as 1967 with the Kalven Report, “independence from political fashions” has been central to the school’s identity. In 2014, the idea of a neutral University with regard to political speech was further entrenched by way of the Chicago principles. The goal of the Chicago principles, to create an on-campus environment that censors no speech and promotes a ready flow of discussion, is well-founded. And by the University’s own metrics, it has been deeply successful; the University, after all, rarely, if ever, engages in politics. That is, in typical times.

The Trump presidency, of course, was far from typical. The crises came quick, and with them came new pressures for the University to engage in politics. As early as January 2017, the travel ban from Muslim-majority countries spurred a large-scale opposition from college administrations including UChicago, with the University joining forces with other schools to file an amicus brief against the action. Likewise, it openly rebuked a slew of Title IX rollbacks by the Department of Education; sued against ICE's barring of international students taking online classes; spoke in favor of the Paris Climate Accords as the U.S. pulled out; and condemned the Trump administration's partial ban on diversity training last fall. While in most of these situations the actual risk to the University was limited because it shared the limelight with whole swathes of academia, the fact that it took positions at all is hugely important, especially when compared to its inaction in the Obama years. In 2010, for example, the University hedged around its support for Dreamers, reaffirming aid for undocumented students while refusing to take the conversation further than its student body. Contrast that with 2017, when it wrote a letter directly to the White House over Trump's attempt to nullify DACA, openly advocating the program’s continuation in full. Both then and now, UChicago has been big enough to have a voice in the national conversation, and with that comes the responsibility to use it for good—or at least to use it to oppose what’s blatantly wrong. It took the egregious actions of the Trump presidency, but the University seems to have finally accepted at least some of that responsibility.

Yet for all its newfound engagement, UChicago has also stumbled in many ways in its response to the Trump years—typically when it made the choice not to speak up. For one, even when the University opposed Trump’s actions, that opposition often seemed almost intentionally soft. The University’s decision to publish its own document about the Paris Accords instead of the near-universally supported document along with the rest of academia was likely made so that they could have softer language, language that avoided reference to the former president altogether. In its letter objecting to diversity training restrictions, the University took great lengths to avoid publicly supporting the practice; instead, it framed its opposition around the government dictating what speech is okay.

Reservations like these are endemic to the University’s philosophy, drawing from decades of focus on an apolitical public presence as central to campus discussion. Even still, these shifts towards engagement are substantial, and they represent a net positive. The pillar of free speech—which the University’s neutrality is supposed to support in the first place—requires a healthy political environment where the shared interest of the University community is protected, and where every member of the community is offered an equal platform for their voice to be heard. Trump made it clear that the government can act against these interests, and UChicago’s call to meaningfully object to that is heartening. By taking active political stances through court action or public statements on key issues that affect the campus community or impact the people's equal opportunity to speak, the University is actually doing a better job of building the culture that the Chicago principles espouse. Given its reservations, even during Trump’s administration, there is a long way to go before the University has done all that it should to fully realize this equal platform, but its decisions to take the stands it did over the past four years set it on the right path.

Now that the Trump administration is out and Biden is in, though, the willingness of the University to engage politically has been complicated. On one hand, a more measured leader like Biden means that the need for the University to make a political stand decreases dramatically. In fact, the new White House has already reversed the most high-profile moves of the past four years: it rejoined the Paris Climate Accords, ended travel restrictions against Muslim countries, and revoked restrictions on diversity training, all within its first week. With Biden, it seems that there will simply be less federal action that UChicago would object to, and so you’d expect the University to take a less involved role on policy matters as a result. Fair, but even still, there are ways for Chicago to stay meaningfully involved in the public discourse: If Biden adopts a policy that’s in the interest of the University community, it should vocalize its support—and if he adopts policy against this interest, it should act just as strongly in condemnation.

This, as we’ve seen, will likely be an uncomfortable position to take. It is also, however, one that it has an obligation to fulfill. The egregiousness of the Trump administration's policies has finally spurred our campus to recognize this, but that’s just gotten the ball rolling. To keep pushing it forward, the University must stay engaged even under friendlier administrations, remembering its responsibility to protect the interests of its broader community.

Nischal Sinha is a first-year in the College.