Arriving on campus this January, I found myself standing outside of the room in which I normally get tested. After a few confusing minutes and several text messages, I eventually found out that it would be another five days after I got to campus until I would receive my first COVID-19 test. It was decisions like this that made up the University’s plan to bring students back to campus for winter quarter, a plan with several glaring holes that sent a message that the University community is being held to different rules from the rest of the South Side. From January 11 through February 8, the City of Chicago mandated that travelers arriving from 48 states and two territories—that is, from everywhere in the U.S. but Hawaii—follow a 10-day quarantine or test negative within three days prior to their arrival and adhere strictly to “masking, social distancing, and avoidance of in-person gatherings.” The plan developed by the University “in consultation with CDPH [the Chicago Department of Public Health] and experts at UChicago Medicine” stands in stark contrast to this citywide plan. Students are only required to follow the University’s seven-day “stay at home” quarantine policy upon arriving on campus. This policy does not call for students to get a COVID-19 test before traveling to Chicago or immediately upon arrival at school, and it allows students to leave their residential halls for “groceries and food, medical care and supplies, and outdoor exercise.” And while the University explicitly endorses outdoor exercise for students, it also quietly contradicts its own directives—as I found out when my suitemate returned one day dripping in sweat—by allowing all students to exercise indoors at the athletic center during their quarantine period. The University must immediately rectify these obvious instances of complacent COVID-19 planning, all of which demonstrate that it’s not fighting the spread of this virus with necessary diligence.

It is shocking that the University saw it as necessary to test students immediately upon arrival during autumn quarter, but no longer deemed it important when winter quarter began, especially given the increasingly dire state of the virus in the U.S. and abroad. Some may cite the fact that COVID-19 may not be detectable until roughly five days after transmission, so waiting this long allows for more accurate testing should a student contract the virus en route to the school. Yet this disregards the possibility that students had already contracted the virus before departing their homes. The University has no reason not to test students when they first get to campus in addition to regular testing beginning approximately five days later.

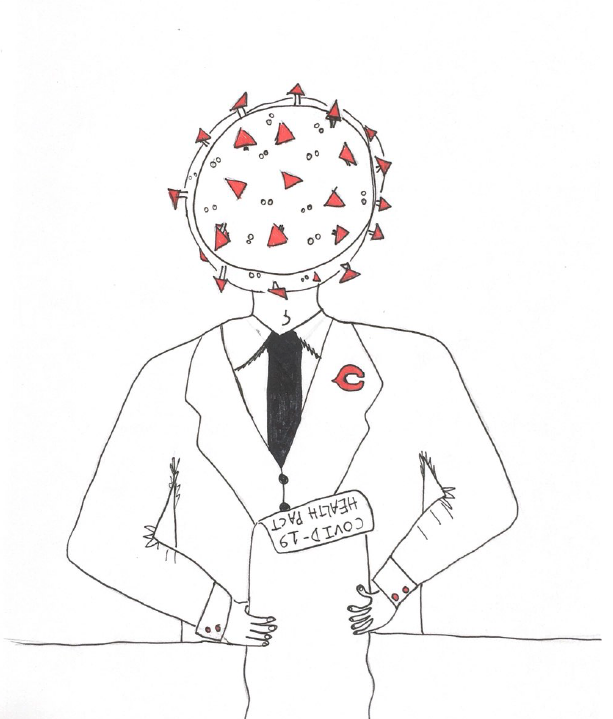

While there’s no published proof of this, friends, social media, and first-hand experience all confirm that fraternities on campus continue to operate more or less as they would in a normal year, holding in-person rush events and parties. This trend warrants a Viewpoints column of its own. Regardless, given the violations of the UChicago Health Pact that have occurred and will occur simply by bringing students back to Hyde Park—evinced best by fraternities—testing upon arrival going forward is incredibly important. To my knowledge, several frat parties took place during the “stay at home” order. And while the University seemingly has no intention of preventing these events from taking place, they should at the very least operate under the assumption that they do by testing rapidly and liberally to keep cases to a minimum.

All that said, credit must be given where it’s due. Campus data on COVID-19 testing, both this quarter and last quarter, demonstrates that the University has successfully minimized the presence of the virus on campus. For this, as a student and member of the community, I’m grateful. Yet the same policies that have been successful at managing statistics have been far less successful when it comes to managing actual people. Leaving gyms open and not requiring students to test immediately upon both arrival and after five days of quarantine are questionable decisions. Although evidently not critical to preventing a massive outbreak, closing gyms and increasing testing are obvious steps the University could take to prevent viral transmission—and it seems foolish not to.

When the University makes such loose decisions as they have—decisions an average student would, in my experience, balk at—it creates vagueness and confusion regarding its directives, undermining trust and efficacy. Last quarter, Emily Landon, the executive medical director for infection prevention and control at UChicago Medicine, told students that they should only have “five up-close contacts in their friend group.” But what this actually meant is still unclear. One resident assistant ran up against this problem when confronting several students congregating in a single room, ostensibly violating the UChicago Health Pact, who cited Landon’s speech in their defense. Housing & Residence Life’s policy—only one extra person per room, masks on—doesn’t match the University’s own advice.

When messaging from the University is self-contradictory and unclear, people are less likely to take what it says seriously. Not testing upon arrival, keeping gyms open during quarantine, and making ill-defined rules for socializing all signal to undergraduates that things are different for our community. The data backs up this claim, showing that we can abide by shockingly loose COVID-19 measures while avoiding massive outbreaks because of the vast resources we can put behind testing, contact tracing, and the like. Despite the questionable sense of security these resources have given the University, we’re susceptible to the virus just like everyone else.

While writing this column, I was informed that a close friend was experiencing COVID-like symptoms. As soon as I heard the news, a wash of concern came over me, alongside the questions we all dread having to ask—Is my friend okay? Do I have COVID? Who have I seen recently?—that make daily concerns about being a student feel trivial. It’s easy to look at the data and only feel gratitude. And for the most part, that’s absolutely what I feel. But it’s also easy to forget that each number you see, each positive COVID-19 case, is a person with friends and loved ones. It’s easy to brush off the negligence of the University in not testing students upon arrival or in their vague messaging, citing their overall success—at least until you or someone you care about becomes one of these statistics.

For a school that leans so heavily on theory, it makes sense that we could be lulled into a sense of complacency through impressive data. Yet those involved in the ongoing planning process must stay grounded and aware of the effects of their policies and the messaging they send to members of our community. Establishing stricter COVID-prevention guidelines—temporarily closing indoor gyms and reinstating testing on arrival to campus—is the perfect place to start. And, although by definition harder to measure, awareness of the qualitative effects of University COVID-19 policies is long overdue.

Clark Kovacs is a first-year in the College.